![What became of us]()

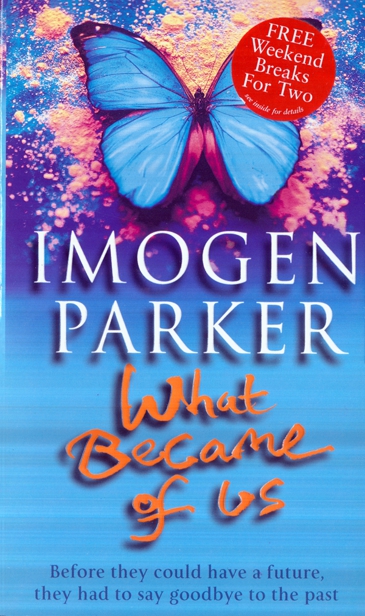

What became of us

the new house, but he did not know whether he would be able to deliver it. He wished he had paid more attention on those ^terminable trips to Homebase.

Roy closed the bedroom door and then the bathroom, trying to picture how that had been then, but there hadn’t been an upstairs bathroom then, he remembered, only one downstairs, through the kitchen. He could recall the coldness of the kitchen lino on the soles of his bare feet, as he tiptoed through in the middle of the night for a pee, terrified of waking one of the women.

His daughters were in the car, strapped into their car seats, each holding a brand new Barbie doll. He’d resisted the purchase for a long time, disapproving of the American plastic dolls, and had felt a sense of defeat as he finally handed over his credit card to pay for them. He didn’t know whether he was buying them as bribes, or simply to distract his daughters from the trauma of leaving their home. Either way, he knew that he should have found the energy and words to explain why they were going, rather than covering up with toys that millions of pounds of advertising made them think they desired. But seeing their happily absorbed faces through the back window of the old Volvo, he felt that the dolls could not be doing them too much harm, or perhaps they were relieved to be leaving too.

‘OK. Have you said goodbye enough?’ he asked them, climbing into the driver’s seat.

‘It’s only a house, Daddy,’ Saskia told him.

‘In fact, I’ve said goodbye a thousand times,’ Lily added.

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ Saskia admonished her younger sister.

‘Loads of times,’ Lily qualified. ‘Are we going to move into our new house today?’ she asked, as he flicked on the indicator and tried to pull the car out of its cramped parking place in one revolution of the steering wheel.

‘Not today. Soon. We’re going to be staying with Grandma and Grandpa for a little while.’

‘Oh.’

‘It’ll be a bit like a holiday, until we move to our cottage,’ he suggested.

In the rearview mirror, he could see Lily’s lip quivering. These days, she was very inclined to cry when denied precisely what she wanted. It was wearing.

‘Manon’s going to take us punting tomorrow,’ Saskia reminded her, and her younger sister’s face brightened instantly.

‘Is she?’ Roy looked in the mirror. It was the first he had heard of it. ‘On Sunday, we’re going to have lunch with your Auntie Ursula and Annie.’

‘Oh!’ Lily’s lip began to quiver again.

‘Annie always brings us nice presents.’ Again Saskia knew exactly what to say.

She was only five years old, but already she was just like her mother, Roy thought.

At the end of the street, he wound down the window and looked back as if the house would disappear when the car turned out onto Walton Street and he would never see it again.

Suddenly, he wished, like Lily, that they were going to move straight into the cottage he had made an offer on. But there had been something wrong with the survey which involved estimates and further negotiation. He hadn’t wanted to lose the sale of the house in Oxford and have to start all over again, so he had agreed to complete on the sale of the old house before exchanging contracts on the new place. Their furniture had gone into storage. Technically they were now homeless.

He remembered somebody telling him once that moving house was the second most stressful human experience after death of a close relative.

He wanted it to be over so that they could start their new life.

Chapter 5

‘Wear something you’ve always dreamed of wearing ...’

The words slid across the bottom of the card, then up slightly, so that there were two exactly similar instructions joined together like an ink blot, then they shrank back on top of one another. Annie looked up, caught the cab driver’s weary expression in the rearview mirror, and realized that the taxi had come to a standstill.

‘Oh, that was quick,’ she said, as clearly and brightly as she could. She never knew whether she should talk to the back of the taxi driver’s head or to the reflection of his face in the mirror.

He switched on the interior light.

‘Twelve pounds.’

Resentment at the implication that she was too drunk to read the meter mingled with relief that the figure was 12 and not 72 as she had momentarily feared.

The drawstring on her evening bag had become wrapped round her wrist, cutting off both the blood supply to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher