![What became of us]()

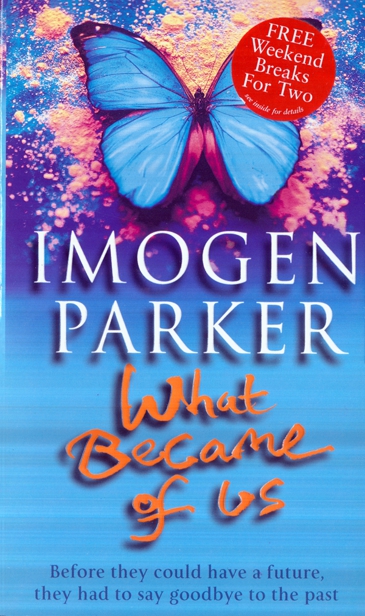

What became of us

saw her coming. She felt as if she had been tried and found guilty of Carl’s murder.

If it hadn’t been for Penny, she didn’t know whether she would have survived. Penny was the only one who tried to understand what she was going through. Before Mods, Manon had only ever spoken to Penny in the Anglo-Saxon tutorials they had shared during the first term. The pressure of work at Oxford made it frighteningly easy not to speak to a soul for weeks on end.

After their first exam, Penny approached her.

‘I’m going to go and get us both some lunch, then you won’t have to run the gauntlet outside,’ she announced.

And before Manon could say anything, she disappeared, reappearing five minutes later with cream cheese sandwiches from the cafe across the road from Schools.

‘I forgot to ask you what you wanted,’ she said, ‘but cream cheese is easy to eat when your tummy’s full of nerves, isn’t it?’

And to Manon, who didn’t know when she had last eaten, the soft white bread and soft white filling of the sandwiches had tasted ambrosial.

‘We’re not supposed to be here between exams,’ Penny said, sitting down on the cold stone staircase, ‘but I had a word, and they’re going to make an exception.’

The Examination Schools had emptied for lunch and her voice echoed around the cool stone chambers. Manon sat down on a lower step, stunned that Penny had managed to charm the brutish university officials who wore bowler hats and were known as bulldogs.

‘Don’t you have to...?’ she had faltered, suddenly so tired from the effort of holding herself together, she could not even finish her thought.

‘What I don’t know now, I’m not going to find out in the next hour, am I?’ Penny interrupted the rest of the sentence.

For a while they said nothing, then Penny seemed to sense that the weight of the silence between them was becoming difficult to bear and said, ‘Please say if you don’t want to talk about it, but if you do, I’ll be glad to listen.’

And Manon had known that the offer was genuinely altruistic and not in the least prurient. She had felt Penny’s sympathy right in the core of her, and she had begun to tell her how terribly lonely she was.

After Mods, Manon had returned to Paris for the summer. It had been easier there, speaking a different language, anonymous in a great city where nobody looked at her twice in the street trying to figure out where they had seen her face. She had almost decided not to return to Oxford, when her results arrived. She had a first. And then Penny had called on her way home from an Inter-Rail trip around Europe. They had coffee together between trains on the concourse of the Gare du Nord, and Penny had offered her a room in the house on Joshua Street. She thought she would be safe there, and so she had returned.

Nobody mentioned Carl again during her time in Oxford, until almost the end, just before finals, when the university paper ran an article about contemporary Oxford characters which compared Manon to Zuleika Dobson, Max Beerbohm’s fictional beauty who had cost a whole college of Oxford undergraduates their lives. The day after exams finished, Manon left Oxford vowing never to return. It was a promise she had kept until Penny’s thirty-eighth birthday party.

‘I lived upstairs from you in the first year,’ Gillian was saying.

Manon only vaguely remembered her. She racked her brain for something sensible to say.

‘I thought your book was absolutely brilliant,’ Gillian went on. ‘We all read it at our book group and I’m afraid I was a bit of a show-off, because I knew you.’

‘Oh. Thank you,’ Manon said, bewildered by the fact that another unlikely person had read her stories.

‘Do you live in London now?’ the woman continued.

‘Yes.’

‘Perhaps you’d come to one of our evenings and talk to us about your writing?’

I haven’t got anything to say about it, Manon thought.

‘Well, if you…’ she nodded.

‘Oh good! Shall we swap numbers now? We’ll only forget later.’

‘I don’t have a number,’ Manon said, ‘but you can always leave a message at the Compton Club in Soho.’

When she had first moved into her flat, the phone had been disconnected and she hadn’t been able to afford the reconnection charge. She knew very few people in London, and anyone could find her at the club if they wanted to. She had grown to like the fact that no-one, not even a voice, could enter her home without her

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher