![What became of us]()

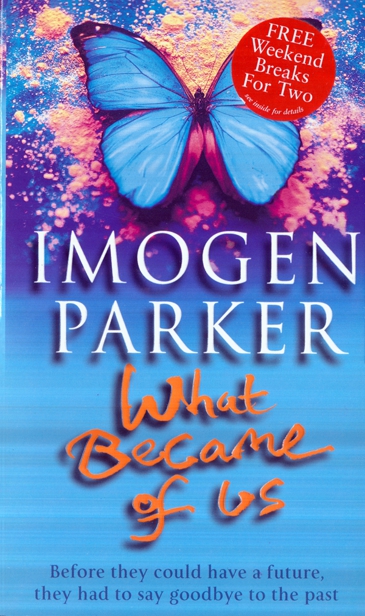

What became of us

taken him upstairs and shown him how to cheat the meter on the ugly gas fire that had taken up so much space in her little room.

They both walked determinedly past the foot of the staircase and he showed her into the long-knocked-through room which had been two rooms when they were students. Ursula’s at the front, and the communal sitting room at the back.

When Penny had returned from Africa, she had thrown herself into renovating and redecorating the house, spending all her spare time and money undoing the ‘improvements’ that had been made to the house before she had owned it. She had been particularly proud of the cast iron Victorian fireplace with patterned tile surround which she had rescued in pieces from a builder’s skip all on her own in the middle of the night.

They sat down on the carpeted floor in front of it, a yard or so away from each other, their eyes gradually adjusting to the darkness.

‘We were going to strip the floor once the girls were a little older,’ Roy said.

‘Yes,’ said Manon, then, taking courage, she asked, ‘What are we doing here?’

He thought for a long time, then he said, carefully, ‘I was her husband and you were her best friend, and we should be able to talk to each other.’

‘But it’s not as simple as that, is it?’ She sat up straight, immediately on the defensive.

‘I know that you suffer. And I do too...’ his voice trailed away.

Manon remembered one of her last sensible conversations with Penny.

‘List...’ she had said, blinking agitatedly with her eyes until Manon understood and took the notepad and biro that were permanently on her bedside table. Then as she fell in and out of consciousness, Manon had obediently written down what she said.

‘The girls, the girls, and... I do want you to be a friend to the girls.’

It was as if she feared saying anything else in case anyone should mistake her. It was almost as if she dared not name either one in case her strength would fail before she could name the other. And so the litany went on, the girls, the girls, the girls, and just once she had said, in a barely audible whisper, Roy.

Manon had not known whether she was supposed to get him from downstairs or to be a friend to him too.

* * *

‘I’m sorry,’ Manon said softly.

‘No, don’t be sorry,’ he said.

They were talking at cross purposes even though they were not really speaking.

‘I’m not sorry in the way that you think.’ She tried to keep her voice level.

‘How then?’ he asked.

He was so gentle, so much more gentle than any man she had ever known and it frightened her.

‘Somebody told me this evening that there are certain distinct stages of grief,’ she began to explain, ‘and one of them is anger, and I think I am still very angry with you for letting Penny be ill. I know, I know that it wasn’t your fault, but I suppose I think that you should have known, you should have noticed the lump in her breast before, or you should have made them do a biopsy straight away. You should have questioned the GP who said it was a cyst, and if you couldn’t find the courage to do that, then at least you could have asked someone else. You could have rung me...’

She realized the futility of her words as they hurried out of her mouth. Locked away in the mind, the arguments seemed completely coherent, but spoken she knew they were unreasonable.

‘And what would you have done?’ he asked.

‘I would have come back,’ she insisted.

‘Would you? And would that have saved her?’ he asked.

The calm equilibrium of his tone seemed to accuse her.

‘But I didn’t know it was so serious.’ She began to defend herself.

‘And you think that we did? You only saw her towards the end, but she didn’t look like that all the time, you know...’

She could see his eyes quite clearly now.

‘...and all they talk to you about is success rates. They want to keep your spirits up, so they give you statistics about survival rates, and they never bother to update you with new statistics, say, when they find that it’s in the lymphatic system too. You kind of know inside, but you put your trust in them and you don’t want to ask — well, Penny never did — because you don’t want to hear that you might die, because once the words are out, then it’s like you’re admitting that it’s a possibility...’

‘OK, OK...’ Manon interrupted, unable to bear any more.

‘No, not OK. Tell me, should I have written to you and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher