![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

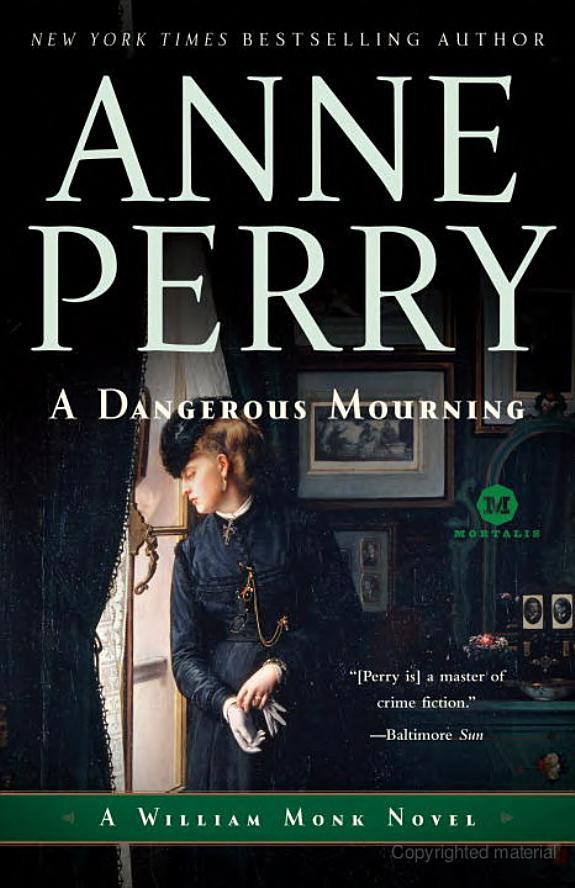

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

me immediately before she went to bed. Her dressing robe was torn. I offered to mend it for her—she was never very good with a needle—” Her voice broke for just a moment. Memory must have been unbearably sharp, and sovery close. Her child was dead. The loss was not yet wholly grasped. Life had only just slipped into the past.

He hated having to press her, but he had to know.

“What did she say to you, ma’am? Even a word may help.”

“Nothing but ‘good night,’ ” she said quietly. “She was very gentle, I remember that, very gentle indeed, and she kissed me. It was almost as if she knew we should not meet again.” She put her hands up to her face, pushing the long, slender fingers till they held the skin tight across her cheekbones. He had the powerful impression it was not grief which shook her most but the realization that it was someone in her own family who had committed murder.

She was a remarkable woman, possessed of an honesty which he greatly respected. It cut his emotion, and his pride, that he was socially so inferior he could offer her no comfort at all, only a stiff courtesy that was devoid of any individual expression.

“You have my deep sympathy, ma’am,” he said awkwardly. “I wish it were not necessary to pursue it—” He did not add the rest. She understood without tedious explanation.

She withdrew her hands.

“Of course,” she said almost under her breath.

“Good day, ma’am.”

“Good day, Mr. Monk. Percival, please see Mr. Monk to the door.”

The footman reappeared, and to Monk’s surprise he was shown out of the front door and down the steps into Queen Anne Street, feeling a mixture of pity, intellectual stimulation, and growing involvement which was familiar, and yet he could remember no individual occasion. He must have done this a hundred times before, begun with a crime, then learned experience by experience to know the people and their lives, their tragedies.

How many of them had marked him, touched him deeply enough to change anything inside him? Whom had he loved—or pitied? What had made him angry?

He had been shown out of the front door, so it was necessary to go around to the back areaway to find Evan, whom he had detailed to speak to the servants and to make at least some search for the knife. Since the murderer was still in the house, and had not left it that night, the weapon must be there too,unless he had disposed of it since. But there would be many knives in any ordinary kitchen of such a size, and several of them used for cutting meat. It would be a simple thing to have wiped it and replaced it. Even blood found in the joint of the handle would mean little.

He saw Evan coming up the steps. Perhaps word had reached him of Monk’s departure, and he had left at the same time intentionally. Monk looked at Evan’s face as he ran up, feet light, head high.

“Well?”

“I had P.C. Lawley help me. We went right through the house, especially servants’ quarters, but didn’t find the missing jewelry. Not that I really expected to.”

Monk had not expected it either. He had never thought robbery the motive. The jewelry was probably flushed down the drain, and the silver vase merely mislaid. “What about the knife?”

“Kitchen full of knives,” Evan said, falling into step beside him. “Wicked-looking things. Cook says there’s nothing missing. If it was one of them, it was replaced. Couldn’t find anything else. Do you think it was one of the servants? Why?” He screwed up his face doubtfully. “A jealous ladies’ maid? A footman with amorous notions?”

Monk snorted. “More likely a secret of some sort that she discovered.” And he told Evan what he had learned so far.

Monk was at the Old Bailey by half past three, and it took him another half hour and the exertion of considerable bribery and veiled threats to get inside the courtroom where the trial of Menard Grey was winding to its conclusion. Rathbone was making his final speech. It was not an impassioned oration as Monk had expected—after all he could see that the man was an exhibitionist, vain, pedantic and above all an actor. Instead Rathbone spoke quite quietly, his words precise, his logic exact. He made no attempt to dazzle the jurors or to appeal to their emotions. Either he had given up or he had at last realized that there could be only one verdict and it was the judge to whom he must look for any compassion.

The victim had been a gentleman of high

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher