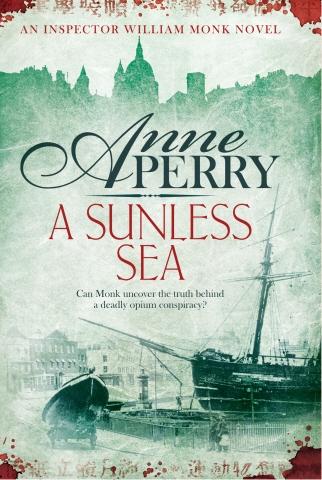

![William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea]()

William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea

when he arrived at the house at five minutes before five that afternoon. It was a respectable family home on a quiet street. The garden was well kept and from the outside it had an air of comfort, even permanence. He would never have associated it with Runcorn.

He was completely taken aback when the door was opened not by Runcorn, or a maid, but by Melisande Ewart, the beautiful widow he and Runcorn had questioned as a witness in a murder some time ago.She had insisted on speaking to them when her overbearing brother had tried, unsuccessfully, to prevent her. Monk had realized at the time that Runcorn had admired her far more than he wished to, and that he would have been mortified with embarrassment had she guessed it. Indeed it was too sensitive even for Monk to have made any remark at the time. If the situation had been less delicate, Monk would have joked about it. Runcorn was the man least likely to fall in love, let alone with a woman of superior social rank and position, even though she had had no money and was dependent upon a brother she found oppressive.

Now she smiled at him with slight amusement and perhaps the faintest flush of color in her cheeks. “Good afternoon, Mr. Monk. How nice to see you again. Please do come in. Perhaps you would like a cup of tea while you discuss the case?”

He found his tongue and thanked her, accepting the offer of tea. A few moments later he was sitting with Runcorn in a small but charming parlor with all the signs of well-accustomed domestic peace. There were pictures on the walls; a vase of flowers on the sideboard, arranged with some artistry; and a sewing box stacked neatly in one corner. The books on the shelf were different sizes, chosen for content, not effect.

Monk found himself smiling. He could not remark on the difference he saw in Runcorn, the inner peace that had eluded the man all his life until now, and was suddenly so overwhelmingly present. Monk could not remember their early friendship, or how it had changed to become so bitter. That was part of his lost past. But he had found enough evidence of his own abrasiveness, the quickness of his tongue, the searing wit, the physical grace, the ease of manner Runcorn could never emulate. Runcorn was awkward, had always been in Monk’s shadow and increasingly lacking in self-confidence with each social failure.

Yet now none of it mattered. Runcorn had taken the past off like an ill-fitting coat and let it drop. Monk was far happier for him than he would have imagined possible. He would probably never know how Runcorn had wooed and won Melisande, who was beautiful, more gracious and infinitely more polished than he. It did not matter.

Runcorn shifted a little self-consciously, as if guessing his thoughts.“These are my notes from the case.” He offered Monk a sheaf of neatly written papers.

“Thank you.” Monk took them and read. Melisande brought the tea, with hot buttered toast and small cakes. She left again with only a word of consideration, no attempt to intrude. They both started to eat.

Runcorn waited patiently in silence until Monk had finished reading and looked up.

“You saw Lambourn where they found him?” he said to Runcorn.

“Yes,” Runcorn agreed. “At least, that’s what the police said.”

Monk caught the hesitation. “You doubt it? Why?”

Runcorn spoke slowly, as if re-creating the scene in his mind. “He sat a little to one side, as if he had lost his balance. His back was against the trunk of the tree, his hands beside him, and his head lolling to one side.”

“Isn’t that what you’d expect?” Monk said with a whisper of doubt. “Why do you think they might have moved him?”

“I thought at first it was just that he didn’t look comfortable.” Runcorn was picking words with uncharacteristic care. “I haven’t seen many suicides, but those who have done it relatively painlessly looked … comfortable. Why would you sit so awkwardly for such a thing?”

“Perhaps he fell awkwardly as he was dying?” Monk suggested. “As you said, as his strength ebbed away, he lost his balance.”

“His wrists and forearms were covered with blood,” Runcorn went on, his face puckered a little at the memory. “And there was some on the front of the thighs of his trousers, but more on the ground.” He looked up at Monk, his eyes steady. “The ground was soaked with blood. But there was no knife. They said he must have thrown it somewhere, or even staggered and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher