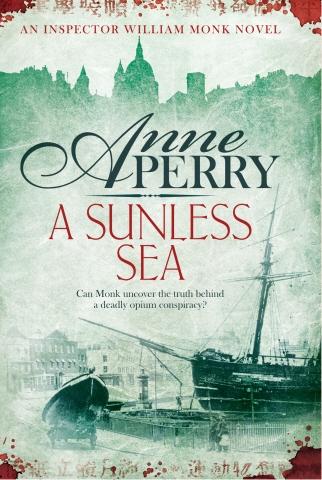

![William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea]()

William Monk 18 - A Sunless Sea

as to which cases to take and which to refuse, at least in theory. In practice it had been very hard work, and financially precarious.

During that time he and Runcorn had crossed paths on a few occasions. Surprisingly, they had each gained a better respect for the other. Later Monk had realized that his own manner had been unnecessarily aggressive, often intolerant. Being in command of men in the River Police had taught him how damaging to a force even one obstructive subordinate can be. It had profoundly changed his view of Runcorn.

When Monk had no longer been his junior in rank, but still constantly a step in front of him in reasoning, Runcorn had developed an appreciation of his skill, and a surprising respect for his courage and the handicap that his amnesia had once been.

Monk had never regained his memory of the majority of his life before the accident. There were occasional flashes, but no complete pictures. The separate pieces did not join up into a whole. Now it no longer haunted him. He did not fear strangers as he once had, always aware that they could know him, and he had no idea whether they were friends or enemies.

Facing Runcorn again was in some ways more awkward than dealingwith someone who did not know him, but at least no explanations would be necessary. For all the enmity they had had over the years, they were past the times of misjudgment.

Monk went to the Blackheath Police Station, where Runcorn was superintendent, and gave his name and rank to the sergeant at the desk.

“The matter is very grave,” he told the man. “It concerns a death in the recent past about which I have further information. Superintendent Runcorn should know immediately.”

Monk was taken up to Runcorn’s office within ten minutes. He went in and was not surprised to see how tidy it was. Runcorn had always been neat to the point of obsession, quite unlike Monk. Now there were even more books than before, but there were also very pleasant pictures on the walls, pastoral landscapes that gave an instant feeling of ease. That was new; quite out of character for the man he had known. There was a vase on a space on one of the shelves, a blue and white painted thing of great delicacy. It might not have been worth much in a monetary sense, but it was lovely, its shape the simplest of curves.

Runcorn himself stood up and came forward, offering his hand. He was a big man, tall and thickening in the middle as he grew older. He seemed grayer than Monk remembered him, but there was none of the inner anger that used to mar his expression. He was smiling. He took Monk’s hand briefly.

“Sit down,” he invited, indicating the chair opposite the desk. “Culpepper said something about information on a recent death?”

Monk had been preparing himself for a completely different reception—in a sense, almost a different man. He was caught off balance. But if he hesitated now it would put him at a disadvantage—something he could not afford with Runcorn—and it would also make him appear less than honest.

“I’ve been working on a particularly brutal murder, a woman whose body was found on Limehouse Pier nearly a fortnight ago,” he began, accepting the proffered seat.

Runcorn’s expression changed instantly into one of revulsion and something that looked like genuine distress.

Again Monk was surprised. He had rarely seen such sensitivity inRuncorn in the past. Only once did he recall a sudden wave of pity, at a graveside. Perhaps that was the moment he had felt the first real warmth toward Runcorn, an appreciation for the man beneath the maneuvering and the aggression.

“Thought you’d arrested someone for that,” Runcorn said quietly.

“I have. Newspapers haven’t got hold of it yet, but it can’t be long.”

Runcorn was puzzled. “What has that to do with me?”

Monk took a deep breath. “Dinah Lambourn.”

“What?” Runcorn shook his head in denial, as if he believed it could not be possible.

“Dinah Lambourn,” Monk repeated.

“What about her?” Runcorn still did not understand.

“All the evidence says that it was she who murdered the woman by the river. Her name was Zenia Gadney.”

Runcorn was stunned. “That’s ridiculous. How would Dr. Lambourn’s widow even know a middle-aged prostitute in Limehouse, still less care about her?” He was not angry, just incredulous.

Monk felt conscious of the absurdity as he answered. “Joel Lambourn was having an affair with Zenia Gadney, over

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher