![Winter in Eden]()

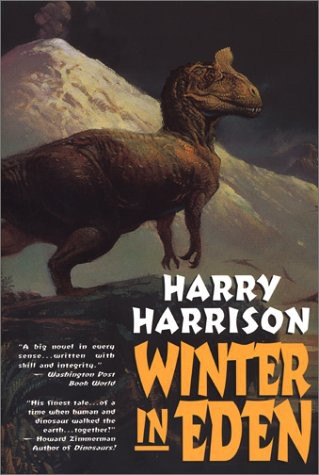

Winter in Eden

days he said. Either they don't count very well—or they don't care."

"A little of both. They don't seem to be worried at all being away from shore like this. How do they find their way and not sail in circles?"

As though in answer to their question, Kalaleq climbed up next to the mast and held to it with one hand, swaying as they rode up on the easy waves. There was no moon, but it was easy to see in the bright starlight. He held something to the sky and looked at it, then shouted instructions to the helmsman who Winter in Eden - Harry Harrison

pulled the steering oar over. The sail flapped a little at this so Kalaleq loosened knots, tightened some lines and let out others, until the sail was angled to their satisfaction. When this was finished Armun called him over and asked him what he had been doing looking at the stars.

"Finding the way back to our paukaruts," he said with some satisfaction. "The stars show us the way."

"How?"

"With this."

He passed over the construction of joined bones. Kerrick looked at it, turning it over before shaking his head and passing it back.

"It makes little sense to me—just four bones tied together at the corners to make a square."

"Yes, of course, you are right," Kalaleq agreed. "But it was tied together by Nanuaq when he was standing among the paukaruts on Allanivok's shore. That is the way it is done. It is an important secret knowledge which I will tell you now. Do you see that star up there?"

With much pointing and shouted help from the others they finally discovered which star he was talking about. Kerrick knew little of the sky; it was Armun who identified it.

"That is Ermanpadar's Eye, that is what I was taught. All the other stars—they are the tharms of brave hunters who have died. Each night they walk up into the sky there in the east, rise up over our heads and then go to rest in the west. They walk together like a great herd of deer and are watched over by Ermanpadar who does not move with them. He stands there in the north and watches, and that star is his eye. It stands still while the tharms go around it."

"I never noticed."

"Watch it tonight—you will see."

"But how does that help us find our way?"

This involved more shouted explanation from Kalaleq, who felt that Kerrick's inability to understand Paramutan was because he was deaf. If he shouted loud enough surely Kerrick would know what he meant. With Armun translating he explained how the frame worked.

"This fat bone, it is the bottom. You must hold it before your eye and look along it at the place where the water meets the sky. Tilt it up and down until you cannot see its length, just the round end. When that is done—and you must keep it pointed correctly at all times—you must quickly look up along this bone which is the Allanivok bone, and look for the star. It must point right at the star. Look, keep trying."

Winter in Eden - Harry Harrison

Kerrick struggled with the frame, blinking and sighting until his eyes were tired and watering. "I cannot do it," he finally said. "When this bone points to the horizon—the other points above the star."

At this Kalaleq gave a shout of joy and called out to the other Paramutan to witness how quickly Kerrick had learned to guide the ikkergak already, his first day out from shore. Kerrick could not understand what the excitement was about since he had got it wrong.

"You are right," Kalaleq insisted. "It is the ikkergak that is wrong. We are too far south. You will see—when we go farther north the bone will point at the star."

"But you said that this star did not move like all the others?"

Kalaleq was hysterical at this and rolled about with laughter. It was some time before he could explain. It appeared that this star did not move unless you moved. If you sailed north it rose higher in the sky, if you went south it became lower. Which meant that for every place you were the star had a certain position in the sky. That was how you found your way. Kerrick was not sure exactly what this meant and fell asleep while still puzzling over it.

Though Kerrick and Armun were always slightly queasy from the bobbing, twisting, rise and fall of the boat, their seasickness did get better after some days at sea. They ate meagerly of the blubber and meat, but finished all of their carefully measured ration of water each day. They helped catch fish because the juice from the fish, freshly squeezed, satisfied their thirst even better than the water did.

Kerrick

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher