![Winter Moon]()

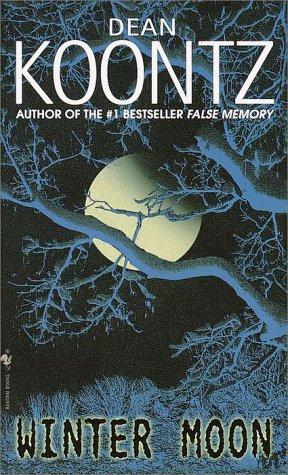

Winter Moon

sunglasses in a dresser drawer. He wished he had ski goggles.

Sunglasses would have to be good enough. He couldn't walk the two miles to Ponderosa Pines with his eyes unprotected in that glare, he'd be risking snowblindness.

When he returned to the kitchen, where Heather was checking the locks on the last of the windows, he lifted the phone again, hoping for a dial tone. Folly, of course. A dead line. "Got to go," he said.

They might have hours or only precious minutes before their nemesis decided to come after them. He couldn't guess whether the thing would be swift or leisurely in its approach, there was no way of understanding its thought processes or of knowing whether time had any meaning to it. Alien. Eduardo had been right. Utterly alien.

Mysterious.

Infinitely strange.

Heather and Toby accompanied him to the front door. He held Heather briefly but tightly, fiercely. He kissed her only once. He said an equally quick goodbye to Toby. He dared not linger, for he might decide at any second not to leave, after all. Ponderosa Pines was the only hope they had. Not going was tantamount to admitting they were doomed. Yet leaving his wife and son alone in that house was the hardest thing he had ever done- harder than seeing Tommy Fernandez and Luther Bryson cut down at his side, harder than facing Anson Oliver in front of that burning service station, harder by far than recovering from a spinal injury. He told himself that going required as much courage on his part as staying required of them, not because of the ordeal the storm would pose and not because something unspeakable might be waiting for him out there, but because, if they died and he lived, his grief and guilt and selfloathing would make life darker than.death.

He wound the scarf around his face, from the chin to just below his eyes.

Although it went around twice, the weave was loose enough to allow him to breathe. He pulled up the hood and tied it under his chin to hold the scarf in place. He felt like a knight girding for battle. Toby watched, nervously chewing his lower lip. Tears shimmered in his eyes, but he strove not to spill them.

Being the little hero, so the boy's tears would be less visible to him and, therefore, less corrosive of his will to leave.

He pulled on his gloves and picked up the Mossberg shotgun. The Colt .45 was holstered at his right hip. The moment had come. Heather appeared stricken. He could hardly bear to look at her. She opened the door. Wailing wind drove snow all the way across the porch and over the threshold. Jack stepped out of the house and reluctantly turned away from everything he loved. He kicked through the powdery snow on the porch. He heard her speak to him one last time-"I love you"-the words distorted by the wind but the meaning unmistakable. At the head of the porch steps he hesitated, turned to her, saw that she had taken one step out of the house, said, "I love you, Heather," then walked down and out into the storm, not sure if she had heard him, not knowing if he would ever speak to her again, ever hold her in his arms, ever see the love in her eyes or the smile that was, to him, worth more than a place in heaven and the salvation of his soul.

The snow in the front yard was knee-deep. He bulled through it. He dared not look back again. Leaving them, he knew, was essential. It was courageous. It was wise, prudent, their best hope of survival.

However, it didn't feel like any of those things. It felt like abandonment.

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE.

Wind hissed at the windows as if it possessed consciousness and was keeping watch on them, thumped and rattled the kitchen door as if testing the lock, shrieked and snuffled along the sides of the house in search of a weakness in their defenses.

Reluctant to put the Uzi down in spite of its weight, Heather stood watch for a while at the north window of the kitchen, then at the west window above the sink. She cocked her head now and then to listen closely to those noises that seemed too purposeful to be just voices of the storm.

At the table, Toby was wearing earphones and playing with a Game Boy.

His body language was different from that which he usually exhibited when involved in an electronic game-no twitching, leaning, rocking from side to side, bouncing in his seat. He was playing only to fill the time.

Falstaff

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher