![Winter Moon]()

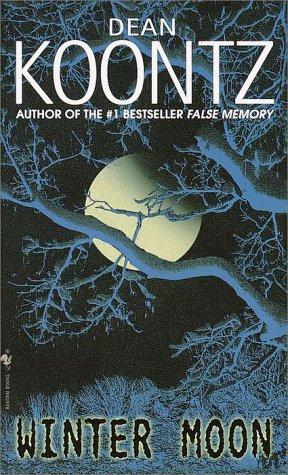

Winter Moon

pines on the western foothills and from there into the mountains. It might long ago have retreated into some high redoubt, secluded ravine, or cavern in the remote reaches of the Rocky Mountains, many miles from Quartermass Ranch.

But he didn't think that was the case.

Sometimes, when he was walking near the forest, studying the shadows under the trees, looking for anything out of the ordinary, he was aware of

a presence. Simple as that. Inexplicable as that. A presence.

On those occasions, though he neither saw nor heard anything unusual, he was aware that he was no longer alone. So he waited.

Sooner or later something new would happen.

On those days when he grew impatient, he reminded himself of two things.

First, he was well accustomed to waiting, since Margaret had died three years ago, he hadn't been doing anything but waiting for the time to come when he could join her again. Second, when at last something did happen, when the traveler finally chose to reveal itself in some fashion, Eduardo more likely than not would wish that it had remained.concealed and secretive.

Now he picked up the empty beer bottle, rose from the rocking chair, intending to get another brew-and saw the raccoon. It was standing in the yard, about eight or ten feet from the porch, staring at him. He hadn't noticed it before because he'd been focused on the distant trees-the once-luminous trees-at the foot of the meadow.

The woods and fields were heavily populated with wildlife. The frequent appearance of squirrels, rabbits, foxes, possums, deer, horned sheep, and other animals was one of the charms of such a deeply rural life.

Raccoons, perhaps the most adventurous and interesting of all the creatures in the neighborhood, were highly intelligent and rated higher still on any scale of cuteness. However, their intelligence and aggressive scavenging made them a nuisance, and the dexterity of their almost hand-like paws facilitated their mischief. In the days when horses had been kept in the stables, before Stanley Quartermass died, raccoons-although primarily carnivores-had been endlessly inventive in the raids they launched on apples and other equestrian supplies.

Now, as then, trash cans had to be fitted with raccoon-proof lids, though these masked bandits still made an occasional assault on the containers, as if they'd been in their dens, brooding about the situation for weeks, and had devised a new technique they wanted to try out.

The specimen in the front yard was an adult, sleek and fat, with a shiny coat that was somewhat thinner than the thick fur of winter. It sat on its hindquarters, forepaws against its chest, head held high, watching Eduardo. Though raccoons were communal and usually roamed in pairs or groups, no others were visible either in the front yard or along the edge of the meadow.

They were also nocturnal. They were rarely seen in the open in broad daylight.

With no horses in the stables and the trash cans well secured, Eduardo had long ago stopped chasing raccoons away-unless they got onto the roof at night. Engaged in raucous play or mouse chasing across the top of the house, they could make sleeping impossible.

He moved to the head of the porch steps, taking advantage of this uncommon opportunity to study one of the critters in bright sunlight at such close range.

The raccoon moved its head to follow him.

Nature had cursed the rascals with exceptionally beautiful fur, doing them the tragic disservice of making them valuable to the human species, which was ceaselessly engaged in a narcissistic search for materials with which to bedeck and ornament itself. This one had a particularly bushy tail, ringed with black, glossy and glorious.

"What're you doing out and about on a sunny afternoon?" Eduardo asked..The animal's anthracite-black eyes regarded him with almost palpable curiosity.

"Must be having an identity crisis, think you're a squirrel or something."

With a flurry of paws, the raccoon busily combed its facial fur for maybe half a minute, then froze again and regarded Eduardo intently.

Wild animals-even species as aggressive as raccoons-seldom made such direct eye contact as this fellow. They usually tracked people furtively, with peripheral vision or quick glances. Some said this reluctance to meet a direct gaze for more than a few

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher