![A Darkness in My Soul]()

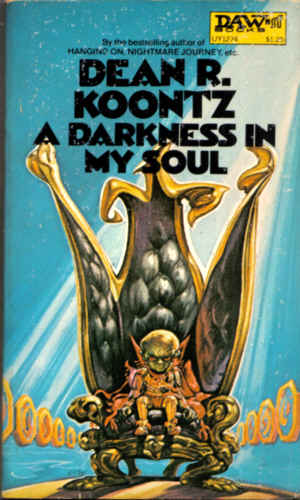

A Darkness in My Soul

cursed the womb which had made me, beseeching the gods to melt its plastic walls and short-circuit those miles and miles of delicate copper wires.

I pulled on street clothes over pajamas, stepped into overshoes and a heavy coat with fur lining, one of the popular Nordic models. Without Harry Kelly, I would most likely have been in prison at that moment-or in a preventive detention apartment with federal plainclothes guards standing watch at the doors and windows. Which is only a more civilized way of saying the same thing: prison.

When the staff of Artificial Creation discovered my wild talents in my childhood, the FBI attempted to "impound" me so that I might be used as a "national resource" under federal control for "the betterment of our great country and the establishment of a tighter American defense perimeter."

It had been Harry Kelly who had cut through all that fancy language to call it what it was-illegal and immoral imprisonment of a free citizen. He fought the legal battle all the way to nine old men in nine old chairs, where the case was won. I was nine when we did that-twelve long years ago.

It was snowing outside. The harsh lines of shrubbery, trees, and curbs had been softened by three inches of white. I had to scrape the windscreen of the hovercar, which amused me and helped settle my nerves a bit. One would imagine that, in 2004 A.D., Science could have dreamed up something to make ice scrapers obsolete.

At the first red light, there was a gray police howler overturned on the sidewalk, like a beached whale. Its stubby nose had smashed through the display window of a small clothing store, and the dome light was still swiveling.

A thin trail of exhaust fumes rose from the bent tailpipe, curled upwards into the cold air. There were more than twenty uniformed coppers positioned around the intersection, though there seemed to be no present danger. The snow was tramped and scuffed, as if there had been a major conflagration, though the antagonists had disappeared. I was motioned through by a stern-faced bull in a fur-collared fatigue jacket, and I obeyed. None of them looked in the mood to satisfy the curiosity of a passing motorist, or even to let me pause long enough to scan their minds and find the answer without their knowledge.

I arrived at the AC building and floated the car in for a Marine attendant to park. As I slid out and he slid in, I asked, "Know anything about the howler on Seventh?

Turned on its side and driven halfway into a store. Lot of coppers."

He was a huge man with a blocky head and flat features that looked almost painted on. When he wrinkled his face in disgust, it looked as if someone had put an eggbeater on his nose and whirled everything together.

"Peace criers," he said.

I couldn't see why he should bother lying to me, so I didn't go through the bother of using my esp, which requires some expenditure of energy. "I thought they were finished," I said.

"So did everyone else," he said. Quite obviously, he hated the peace criers, as did most men in uniform. "The Congressional investigating committee proved the voluntary army was still a good idea. We don't run the country like those creeps say. Brother, I can sure tell you we don't!" Then he slammed the door and took the car away to park it while I punched for the elevator, stepped through its open maw, and went up.

I made faces at the cameras which watched me, and repeated two dirty limericks on the way to the lobby.

When the lift stopped and the doors opened, a second Marine greeted me, requested that I hold my fingertips to an identiplate to verify his visual check. I complied, was approved, and followed him to another elevator in the long bank. Again: up.

Too many floors to count later, we stepped into a cream-walled corridor, paced almost to the end of it, and went through a chocolate door that slid aside at the officer's vocal command. Inside, there was a room of alabaster walls with hex signs painted every five feet in brilliant reds and oranges. There was a small and ugly child sitting in a black leather chair, and four men standing behind him, staring at me as if I were expected to say something of monumental importance.

I didn't say anything at all.

The child looked up, his eyes and lips all but hidden by the wrinkles of a century of life, by gray and gravelike flesh. I

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher