![Always Watching]()

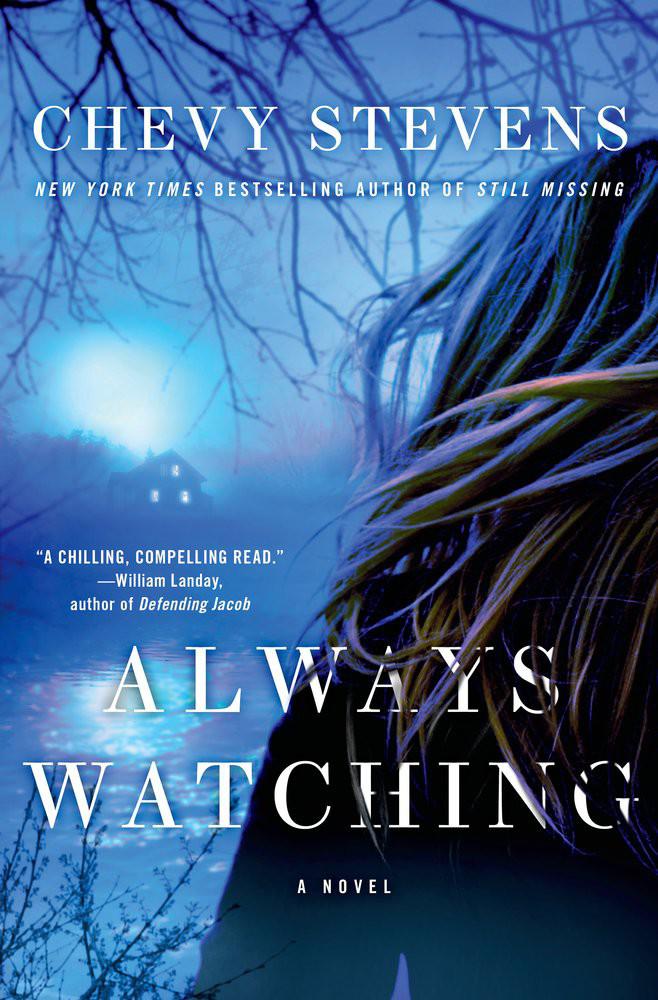

Always Watching

was stealing away my sweet daughter, who used to foster animals and friends, who wanted to be a vet one day like her father. And I despaired when I saw her falling apart in front of me, her cheeks growing hollow, life disappearing from her eyes. When she was a toddler, she’d been a chubby little thing with round-apple cheeks. I used to pretend to nibble them, which would make her squeal with laughter, and her eyes were always her most expressive feature. Now I couldn’t even get her to make eye contact.

I’d ransacked Lisa’s room one day, finding the locked metal box in the back of her closet. I threw everything away, the little baggies, pipes, straws, ashtrays, and mirrors, and when she came home, threatened rehab. She’d begged for a second chance. I gave it, and within weeks, she was staying out all night again. Finally, out of sheer desperation, I sold our house and moved up to Nanaimo, hoping a smaller community might mean less trouble. Even there she found ways. In her last year of school she ran away three times. Still, she managed to graduate, albeit at the very bottom of her class. Now, I thought. Now she’s turning her life around. But my relief was short-lived. The day school ended, she threw some things into a backpack and stormed out of the house. I later learned she’d moved back down to Victoria.

Since then, I’ve tried to keep tabs on her through parents of her friends. She came home one Christmas and spent most of it on her cell phone, while I tried to re-create the magic of her childhood. She’d promised to come home the next Christmas, even phoned a few days early to confirm, but then never showed up. She hadn’t been home since. I’ve kept every present from every Christmas and every missed birthday. But I couldn’t stop missing my daughter.

There wasn’t a night that went by when I didn’t wonder where she was, if she had enough to eat, if she was cold. I tried not to think about how she might be damaging her body, the things she might be doing to get more drugs. Mostly I struggled with guilt. Was it because I was so consumed with my own grief? I should have talked to her more, should’ve found out what was going on earlier.

And underneath that was the shame at my failure as a doctor. When she first started doing drugs, I thought I could help her. I was a psychiatrist, of course I could help my own daughter, but then, when every attempt failed, and she ran away, I thought, What kind of doctor am I? How can I hold myself out as a professional when my drug-addicted daughter is living on the streets?

Sometimes I wondered if the problems started even before Paul became sick. He was a veterinarian, and after we had Lisa I stayed home for a year, then worked part-time at the clinic. When she was five, I decided to become a psychiatrist, a long-held dream that Paul supported, so I went to medical school in Vancouver. Lisa lived with me and also started school. Paul would visit on the weekends. We moved back to the island when Lisa was ten, and I completed my residency at St. Adrian’s. I did my best during those years to balance everything, to be a good wife and mother, but now I’d remember all the times I’d been short with Lisa when I was rushing to class, or told her to be quiet when I was studying—and her disappointed face.

The last time I saw Lisa was eight months ago. After I was attacked outside my office, one of my friends, Connie, had finally tracked her down through some of Lisa’s friends. She’d visited me in the hospital. I’d been thrilled, had wanted to hold and hug her so hard that she could never run away again, but she was edgy, dark circles under her once-gorgeous blue eyes, her tall frame, so like her father’s, painfully thin. Reminding me of Paul before he died. She could barely look at me and only stayed a few minutes, saying she had to meet a friend. I lost track of her after that, her friends changing as fast as her location.

After I moved down to Victoria and discovered that the trail stopped cold for Lisa, I visited the Victoria New Hope Society—they run three shelters for the homeless—with a photo of her, but they wouldn’t give me any information. I wondered if I’d know my own daughter if I saw her. I didn’t even know what color her hair was now. The first time she’d bleached it, I’d tried to understand that she was finding her own way, tried to applaud her individuality, but I’d missed the little girl who wanted to grow up to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher