![Always Watching]()

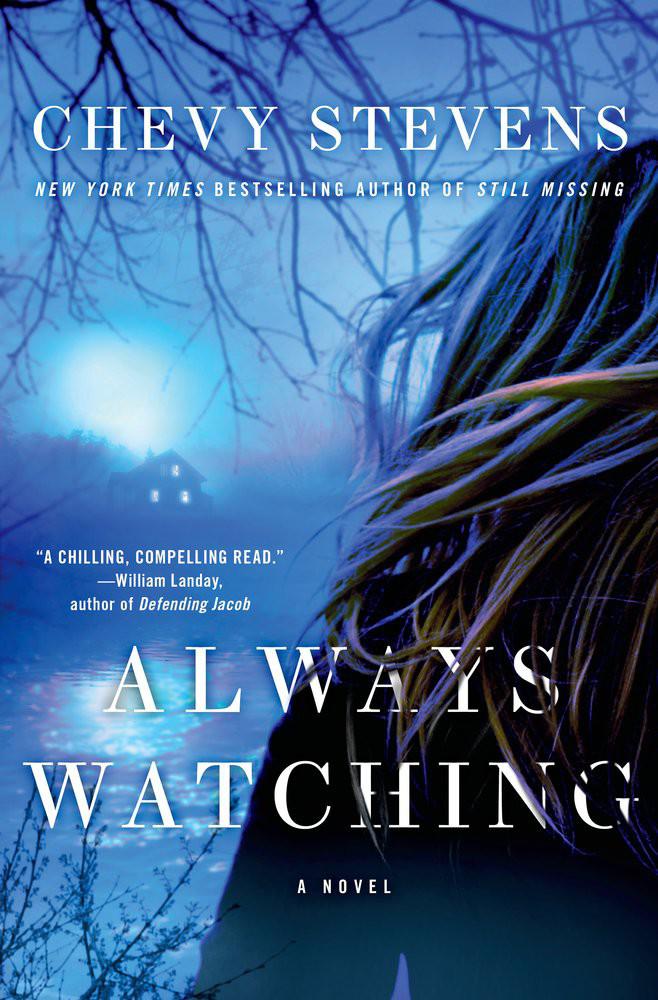

Always Watching

be just like her mother, who used to ask me to braid my hair like hers so we looked the same. We were never the same, though.

She was quiet, and I was communicative, always trying to get to the bottom of things, always wanting to know why people felt the way they did. I wondered if that was one of the many ways I’d gone wrong. Living in a family where nothing was discussed, I’d wanted openness with Lisa, encouraged her to talk about her feelings, to share her thoughts, but she’d always kept her own counsel. That had frustrated me when she was younger, as much as it scared me. It wasn’t until after she moved out I realized that I’d wanted her to share her feelings so I could guide them and control her, so I could keep her safe.

Once in a while on my evening drives, I’d stop and show her photo to some street kids, wondering if Lisa would hear that I was looking for her, worrying that my attempts to find her might just push her away again.

I shouldn’t have worried. It was always the same thing: just another group of kids, with their hoodies, baggy pants, and skateboards, not one of whom had ever laid eyes on my daughter.

* * *

That night, after my fruitless search for Lisa, I pulled in my driveway and as I walked around the corner of my house to my back door, I noticed the black cat stalking a bird. She spotted me, and with a clatter of garbage can lids, leaped on top of the fence. The cat glared down, her skinny tail flicking back and forth—not afraid, angry. I made kissing sounds, but she turned her back and began to lick her paws. I put some tuna on a plate and walked back out. She eyed me from her perch on the fence but wouldn’t come closer, no matter how many enticing sounds I made. I put the dish up on the railing of my deck. In the morning, on my way to the hospital, I noticed happily that the plate of tuna I’d put out the night before had been licked clean. Tonight, when I returned home, I’d put out a blanket-lined box, so she’d have somewhere safe to sleep. My mind flowed back to Lisa, and I wondered where she was staying and if she was warm at night. I wondered if she ever thought of me.

* * *

The nurses told me that Heather wasn’t sleeping as much and had joined another group session the day before, then spent the rest of the day watching TV with some patients—all good signs. During my interview, it was clear she was still struggling with self-esteem issues and guilt about leaving the commune, but I was able to get her to focus on staying in the present as we worked on her care plan.

“What can you do today that might help you?”

She said, “I can join group or take a walk around the ward.”

“Those are great ideas!” We talked about a few more things she could try, then I asked if she was still having thoughts of hurting herself.

“Sometimes, but not as much.” She looked around. “It’s different in here. I’m not as lonely. And the nurses, like Michelle, they’re all really nice. I feel…” She shrugged. “Safer, I guess. Like I’m not weird or bad or something.”

“You’re not. And I’m glad that you’re starting to see that.”

“It’s nice, having someone to listen to you.” She smiled. “I used to listen to Emily when she was upset. We’d go to the barn—she loved horses.”

“Sounds like you were a great support for her.”

“I felt like her big sister.” She paused, thinking. “I showed her how to ride bareback, and we’d go down to the river every day, just to talk.”

As Heather began to describe the trail they took down to the water, my mind filled with images and sounds, the forest cool in the summer, the creak of a saddle, the earthy scent of the woods and horses, and I was pulled back in time.

Willow and I are riding together, bareback through the woods. We pause to let the horses drink from a pool in the river. She’s standing near me, her horse nuzzling her shoulder. She says, “I watch Aaron with you sometimes.…”

My heart starts to thud in my ears, panic digging into my blood.

She’s still talking. “I saw you coming back from the river with him. You looked upset. If there’s anything you ever want to talk about…”

Now my heart’s hitting so hard against my chest, I can barely breathe. Shame, thick and hot, presses down on me.

My voice angry, I say, “There’s nothing to talk about.”

“If he hurt you—”

But I’m already turning, climbing up a log to jump on the back of

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher