![Bloodsucking fiends: a love story]()

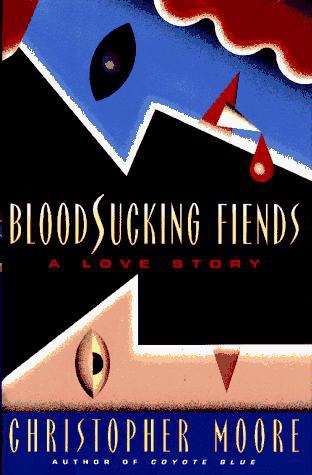

Bloodsucking fiends: a love story

fifty bucks, he thought.

"Bathroom down hall," Wong said, throwing open a door and throwing a light switch. Five sleepy Chinese men looked up from their bunks. "Tommy," Wong said, pointing to Tommy.

"Tommy," the Chinese men repeated in unison.

"This Wong," Wong said, pointing to the man on the bottom left bunk.

Tommy nodded. "Wong."

"This Wong. That Wong. Wong. Wong. Wong," Wong said, ticking off each man as if he were flipping beads on an abacus, which, mentally, he was: fifty bucks, fifty bucks, fifty bucks. He pointed to the empty bunk on the bottom right. "You sleep there. Bye-bye."

"Bye-bye," said the five Wongs.

Tommy said, "Excuse me, Mr. Wong…"

Wong turned.

"When is rent due? I'm going job hunting tomorrow, but I don't have a lot of cash."

"Tuesday and Sunday," Wong said. "Fifty bucks."

"But you said it was fifty dollars a week."

"Two fifty a month or fifty a week, due Tuesday and Sunday."

Wong walked away. Tommy stashed his duffel bag and typewriter under the bunk and crawled in. Before he could work up a good worry about his burning car, he was asleep. He had pushed the Volvo straight through from Incontinence, Indiana, to San Francisco, stopping only for fuel and bathroom breaks. He had watched the sun rise and set three times from behind the wheel – exhaustion finally caught him at the coast.

Tommy was descended from two generations of line workers at the Incontinence Forklift Company. When he announced at fourteen that he was going to be a writer, his father, Thomas Flood, Sr., accepted the news with the tolerant incredulity a parent usually reserved for monsters under the bed and imaginary friends. When Tommy took a job in a grocery store instead of the factory, his father breathed a small sigh of relief – at least it was a union shop, the boy would have benefits and retirement. It was only when Tommy bought the old Volvo, and rumors that he was a budding Communist began circulating through town, that Tom senior began to worry. Father Flood's paternal angst continued to grow with each night that he spent listening to his only son tapping the nights away on the Olivetti portable, until one Wednesday night he tied one on at the Starlight Lanes and spilled his guts to his bowling buddies.

"I found a copy of The New Yorker under the boy's mattress," he slurred through a five-pitcher Budweiser haze. "I've got to face it; my son's a pansy."

The rest of the Bill's Radiator Bowling Team members bowed their heads in sympathy, all secretly thanking God that the bullet had hit the next soldier in line and that their sons were all safely obsessed with small block Chevys and big tits. Harley Businsky, who had recently been promoted to minor godhood by bowling a three hundred, threw a bearlike arm around Tom's shoulders. "Maybe he's just a little mixed up," Harley offered. "Let's go talk to the boy."

When two triple-extra-large, electric-blue, embroidered bowling shirts burst into his room, full of two triple-extra-large, beer-oiled bowlers, Tommy went over backward in his chair.

"Hi, Dad," Tommy said from the floor.

"Son, we need to talk."

Over the next half hour the two men ran Tommy through the fatherly version of good-cop-bad-cop, or perhaps Joe McCarthy versus Santa Claus. Their interrogation determined that: Yes, Tommy did like girls and cars. No, he was not, nor had he ever been, a member of the Communist party. And yes, he was going to pursue a career as a writer, regardless of the lack of AFL-CIO affiliation.

Tommy tried to plead the case for a life in letters, but found his arguments ineffective (due in no small part to the fact that both his inquisitors thought that Hamlet was a small pork portion served with eggs). He was breaking a sweat and beginning to accept defeat when he fired a desperation shot.

"You know, somebody wrote Rambo ?"

Thomas Flood, Sr., and Harley Businsky exchanged a look of horrified realization. They were rocked, shaken, crumbling.

Tommy pushed on. "And Patton - someone wrote Patton ."

Tommy waited. The two men sat next to each other on his single bed, coughing and fidgeting and trying not to make eye contact with the boy. Everywhere they looked there were quotes carefully written in magic marker tacked on the walls; there were books, pens, and typing paper; there were poster-sized photos of authors. Ernest Hemingway stared down at them with a gleaming gaze that seemed to say, "You fuckers should have gone fishing."

Finally Harley said, "Well, if

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher