![Brave New Worlds]()

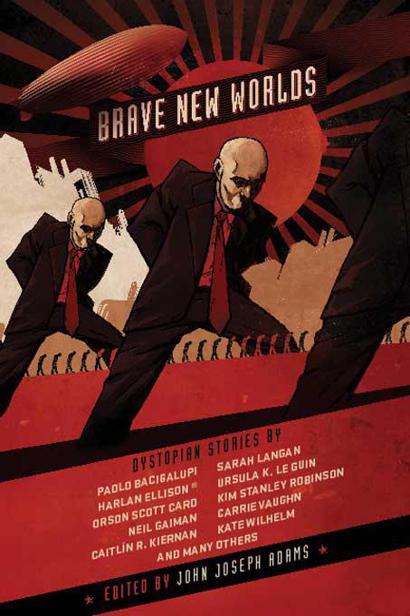

Brave New Worlds

would never have been technically possible—and the first and ultimate imperative of any artist is to create; he has To make his art, whatever the terms. Dad's stuff on Rapa Nui—and at the Taj Mahal, the Forbidden City—was controversial, really, only among the kinds of people who believe, naively, that ideas like "France" and "Japan" are intrinsically more noble, more authentically human, than "Apple Computers" and "Toyota"; that the rules that govern and define our achievements are immutable and unchangeable; that it's not for us to dictate the terms of our own evolution.

But I'll tell you a story—something from a Session not too far back—that connects a few of the ideas I've been talking about, and gets at some of the ways in which my Dad's career, ostensibly so different from my own, converses with my work as an interrogator.

This is the early winter of last year. We're on week three with one of the Islamabad captures. Ali's knuckles are gone; we're moving to dental.

The Objective's not important to this story. Something involving Ali's mom; she's hiding somewhere in Brunei. Ali swears he doesn't know where she's hiding, but it's clear he does. And in the end, a few weeks after the stuff that I'm describing here, he did give us what we needed, and we were able to bring the mother in.

Right now I'm in his mouth with the finest drill, going straight down the middle of every tooth, one after another. That's how we do it: one pass through each tooth with the finest drill bit, and then we stop and interrogate. Then another full pass with a bigger bit, and more questioning. We call them Rinse-and-Repeats. Ali's on a cocktail, now, of Sharpener and Nurturer, which makes the drill work like a light switch: when it's going in, Ali's pain is at the human maximum; the second we stop, he's on cloud nine.

We're on the first pass—I'm entering an incisor—and all of a sudden, Ali's teeth, all of them at once, begin to spray. Eight or nine of them: these fine, crisscrossing sprays arching straight up in the air from the holes in his teeth. Like we'd struck oil.

You ever seen this? I say, sort of to the room. No: nobody's ever seen it. We're all just fascinated, observing this phenomenon. The blood loss is minimal, but the spray is getting pretty far, inking Ali's bib, turning it a very pale pink. Something about this image seems familiar to me—déjà-vu-type familiar—and then I figure it out: Ali looks disconcertingly like the heads from Pier Pierson's Geysers bodywork. From thirty years back. Pierson was the guerilla artist and serial killer who plastinated his victims' heads and installed them, rigged with lights and fountains, in public spaces. A twisted descendant, in some ways, of my father—but let's not start down that road right now.

What's Ali's drug situation? I finally think to ask my Technician.

Euphoric , the Technician says. He's drifting .

I wavered. Let him drift , I finally said. Ali was a CI, I should add, and also just a kid: fourteen, if even that. It wasn't going to hurt to let him float around for a few minutes.

And as he floats, Ali starts smiling—his eyes narrowing like this is the happiest he's ever been. As I'm sure it is. That's one of the uncanny things about this job: in moments like these—and at the end of long sessions, when we inject the Nurturer—our guys have never felt so good in their entire lives.

For a long time, then—a mysteriously long time—we all just stood around Ali and watched. One of my PFCs took off her goggles, and I didn't reprimand her. A little later—it's obvious in retrospect—we figured out the mist from Ali's mouth was leaching Nurturer into the air; that's why we were feeling giddy, and why, for a short time, I was almost hypnotized, was actually seeing rainbows reaching into the room from Ali's mist. At the time, though, it seemed to me that it was just something about the strange sight of that fountain of pink, its queer resemblance to the Pierson heads, that was making me feel this way. Ali, meanwhile, is smiling so hard—so happy—that he's started to cry.

In moments like these—when art intrudes, unexpected, like a ghost—it's easy for me to think that my father is speaking to me. That he's reminding me of why I'm here.

I don't deny the truth of men like Muhyi Al-Din—of the men who've spent, and will spend, their last long years in my interrogation Chairs: there can be heroism in destruction—heroism, as well as art. There

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher