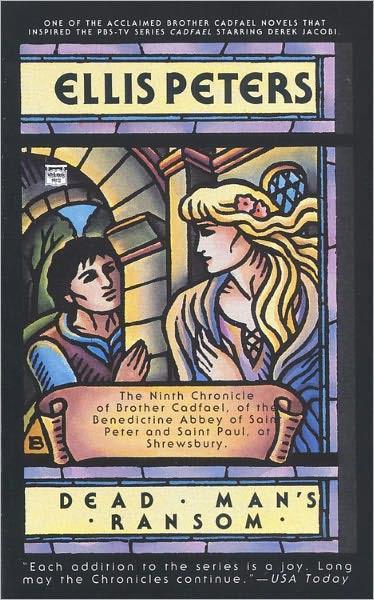

![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

much fallen in flesh, and bore several scars, healed but angry, besides the moist wound in his flank which had gaped again with his fall. Carefully Cadfael dressed and covered the place. Even being handled exhausted the sick man. By the time they had lifted him into the warmed bed and covered him his eyes were again closed. As yet he had not tried to speak.

A marvel how he had ever ridden even a mile before foundering, thought Cadfael, looking down at the figure stretched beneath the covers, and the lean, livid face, all sunken blue hollows and staring, blanched bones. The dark hair of his head and beard was thickly sown with grey, and lay lank and lifeless. Only his iron spirit, intolerant of any weakness, most of all his own, had held him up in the saddle, and when even that failed he was lost indeed.

But he drew breath, he had moved to assert his rights in his own body, however weakly, and again he opened the dulled and sunken eyes and stared up into Cadfael's face. His grey lips formed, just audibly: 'My son?'

Not: 'My wife?' Nor yet: 'My daughter?' Cadfael thought with rueful sympathy, and stooped to assure him: 'Young Gilbert is here, safe and well.' He glanced at Edmund, who signalled back agreement. 'I'll bring him to you.' Small boys are very resilient, but for all that Cadfael said some words, both of caution and reassurance, as much for the mother as the child, before he brought them in and drew aside into a corner to leave them the freedom of the bedside. Hugh came in with them. Prestcote's first thought was naturally for his son, the second, no less naturally, would be for his shire. And his shire, considering all things, was in very good case to encourage him to live, mend and mind it again.

Sybilla wept, but quietly. The little boy stared in some wonder at a father hardly recognised, but let himself be drawn close by a gaunt, cold hand, and stared at hungrily by eyes like firelit caverns. His mother leaned and whispered to him, and obediently he stooped his rosy, round face and kissed a bony cheek. He was an accommodating child, puzzled but willing, and not at all afraid. Prestcote's eyes ranged beyond, and found Hugh Beringar.

'Rest content,' said Hugh, leaning close and answering what need not be asked, 'your borders are whole and guarded. The only breach has provided you your ransom, and even there the victory was ours. And Owain Gwynedd is our ally. What is yours to keep is in good order.' The dulling glance faded beneath drooping lids, and never reached the girl standing stark and still in the shadows near the door. Cadfael had observed her, from his own retired place, and watched the light from brazier and lamp glitter in the tears flowing freely and mutely down her cheeks. She made no sound at all, she hardly drew breath. Her wide eyes were fixed on her father's changed, aged face, in the most grievous and desperate stare.

The sheriff had understood and accepted what Hugh said. Brow and chin moved slightly in a satisfied nod. His lips stirred to utter almost clearly: 'Good!' And to the boy, awed but curious, hanging over him: 'Good boy! Take care... of your mother...' He heaved a shallow sigh, and his eyes drooped closed.

They held still for some time, watching and listening to the heave and fall of the covers over his sunken breast and the short, harsh in and out of his breath, before Brother Edmund stepped softly forward and said in a cautious whisper: 'He's sleeping. Leave him so, in quiet. There is nothing better or more needed any man can do for him.'

Hugh touched Sybilla's arm, and she rose obediently and drew her son up beside her. 'You see him well cared for,' said Hugh gently. 'Come to dinner, and let him sleep.' The girl's eyes were quite dry, her cheeks pale but calm, when she followed them out to the great court, and down the length of it to the abbot's lodging, to be properly gracious and grateful to the Welsh guests, before they left again for Montford and Oswestry.

Over their midday meal, which was served before the brothers ate in the refectory, the inhabitants of the infirmary laid their ageing but inquisitive heads together to make out what was causing the unwonted stir about their retired domain. The discipline of silence need not be rigorously observed among the old and sick, and just as well, since they tend to be incorrigibly garrulous, from want of other active occupation.

Brother Rhys, who was bedridden and very old indeed, but sharp enough in mind and hearing

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher