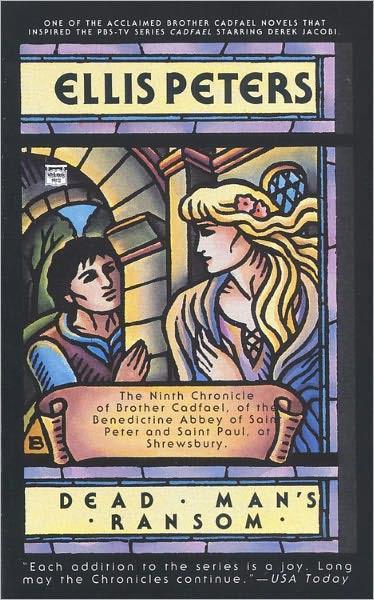

![Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom]()

Brother Cadfael 09: Dead Man's Ransom

even if his sight was filmed over, had a bed next to the corridor, and across from the retired room where some newcomer had been brought during the morning, with unusual to, do and ceremony. He took pleasure in being the member who knew what was going on. Among so few pleasures left to him, this was the chief, and not to be lightly spent. He lay and listened. Those who sat at the table, as once in the refectory, and could move around the infirmary and sometimes the great court if the weather was right, nevertheless were often obliged to come to him for knowledge.

'Who should it be,' said Brother Rhys loftily, 'but the sheriff himself, brought back from being a prisoner in Wales.'

'Prestcote?' said Brother Maurice, rearing his head on its stringy neck like a gander giving notice of battle. 'Here? In our infirmary? Why should they bring him here?'

'Because he's a sick man, what else? He was wounded in the battle, and in no shape to shift for himself yet, or trouble any other man. I heard their voices in there, Edmund, Cadfael and Hugh Beringar, and the lady, too, and the child. It's Gilbert Prestcote, take my word.'

'There is justice,' said Maurice with sage satisfaction, and the gleam of vengeance in his eye, 'though it be too long delayed. So Prestcote is brought low, neighbour to the unfortunate. The wrong done to my line finds a balance at last, I repent that ever I doubted.' They humoured him, being long used to his obsessions. They murmured variously, most saying reasonably enough that the shire had not fared badly in Prestcote's hands, though some had old grumbles to vent and reservations about sheriffs in general, even if this one of theirs was not by any means the worst of his kind. On the whole they wished him well. But Brother Maurice was not to be reconciled.

'There was a wrong done,' he said implacably, 'which even now is not fully set right. Let the false pleader pay for his offence, I say, to the bitter end.'

The stockman Anion, at the end of the table, said never a word, but kept his eyes lowered to his trencher, his hip pressed against the crutch he was almost ready to discard, as though he needed a firm contact with the reality of his situation, and the reassurance of a weapon to hand in the sudden presence of his enemy. Young Griffri had killed, yes, but in drink, in hot blood, and in fair fight man against man. He had died a worse death, turned off more casually than wringing a chicken's neck. And the man who had made away with him so lightly lay now barely twenty yards away, and at the very sound of his name every drop of blood in Anion ran Welsh, and cried out to him of the sacred duty of galanas, the blood feud for his brother.

Eliud led Einon's horse and his own down the great court into the stable, yard, and the men of the escort followed with their own mounts, and the shaggy hill ponies that had carried the litter. An easy journey those two would have on the way back to Montford. Einon ab Ithel, when representing his prince on a ceremonial occasion, required a squire in attendance, and Eliud undertook the grooming of the tall bay himself. Very soon now he would be changing places with Elis, and left to chafe here while his cousin rode back to his freedom in Wales. In silence he hoisted off the heavy saddle, lifted aside the elaborate harness, and draped the saddle cloth over his arm. The bay tossed his head with pleasure in his freedom, and blew great misty breaths. Eliud caressed him absently; his mind was not wholly on what he was doing, and his companions had found him unusually silent and withdrawn all that day. They eyed him cautiously and let him alone. It was no great surprise when he suddenly turned and tramped away out of the stable yard, back to the open court.

'Gone to see whether there's any sign of his cousin yet,' said his neighbour tolerantly, rubbing down one of the shaggy ponies. 'He's been like a man maimed and out of balance ever since the other one went off to Lincoln. He can hardly believe it yet that he'll turn up here without a scratch on him.'

'He should know his Elis better than that,' grunted the man beside him. 'Never yet did that one fall anywhere but on his feet.'

Eliud was away perhaps ten minutes, long enough to have been all the way to the gatehouse and peered anxiously along the Foregate towards the town, but he came back in dour silence, laid aside the saddle, cloth he was still carrying, and went to work without a word or a look aside.

'Not come

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher