![Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice]()

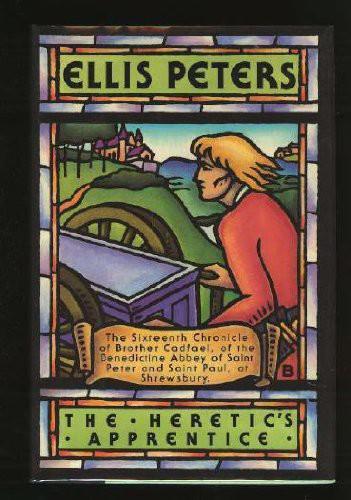

Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice

then, that he did not believe unbaptized children suffered damnation? For that leads to the same end."

"No," said Fortunata. "He never did say what his own belief was in that matter. He was speaking of his master, who is dead. He said that William used to say not even the worst of men could throw a child into the fire, so how could God do so? When he said this," said Fortunata firmly, "he was telling us what William had said, not what he himself thought."

"That is true, but only half the truth," cried Aldwin, "for the next moment I asked him plainly: Do you also hold that belief? And he said: Yes, I do say so."

"Is that true, girl?" demanded Gerbert, turning upon Fortunata a black and threatening scowl. And when she faced him with eyes flashing but lips tight shut: "It seems to me that this witness has no devout wish to help us. We should have done better to take all testimony under oath, it seems. Let us at least make sure in this woman's case." He turned his forbidding gaze hard and long upon the obdurately silent girl. "Woman, do you know in what suspicion you place yourself if you do not speak truth? Father Prior, bring her a Bible. Let her swear upon the Gospels and imperil her soul if she lies."

Fortunata laid her hand upon the proffered book which Prior Robert solemnly opened before her, and took the oath in a voice so low as to be barely audible. Elave had opened his mouth and taken a step towards her in helpless anger at the aspersion cast upon her, but stopped himself as quickly and stood mute, his teeth clenched upon his rage, and his face soured with the bitter taste of it.

"Now," said the abbot, with such quiet but formidable authority that even Gerbert made no further attempt to wrest the initiative from him, "let us leave questioning until you have told us yourself, without haste or fear, all you recall of what went on in that meeting. Speak freely, and I believe we shall hear truth."

She took heart and drew steady breath, and told it carefully, as best she remembered it. Once or twice she hesitated, sorely tempted to omit or explain, but Cadfael noticed how her left hand clasped and wrung the right hand that had been laid upon the open Gospel, as though it burned, and impelled her past the momentary silence.

"With your leave, Father Abbot," said Gerbert grimly when she ended, "when you have put such questions as you see fit to this witness, I have three to put to her, and they encompass the heart of the matter. But first do you proceed."

"I have no questions," said Radulfus. "The lady has given us her full account on oath, and I accept it. Ask what you have to ask."

"First," said Gerbert, leaning forward in his stall with thick brown brows drawn down over his sharp, intimidating stare, "did you hear the accused say, when asked point-blank if he agreed with his master in denying that unbaptized children were doomed to reprobation, that yes, he did so agree?"

She turned her head aside for an instant, and wrung at her hand for reminder, and in a very low voice she said: "Yes, I heard him say so."

"That is to repudiate the sacrament of baptism. Second, did you hear him deny that all the children of men are rotten with the sin of Adam? Did you hear him say that only a man's own deeds will save or damn him?"

With a flash of spirit she said, louder than before: "Yes, but he was not denying grace. The grace is in the gift of choice -"

Gerbert cut her off there with uplifted hand and flashing eyes. "He said it. That is enough. It is the claim that grace is unneeded, that salvation is in a man's own hands. Thirdly, did you hear him say, and repeat, that he did not believe what Saint Augustine wrote of the elect and the rejected?"

"Yes," she said, this time slowly and carefully, "If the saint so wrote, he said, he did not believe him. No one has ever told me, and I cannot read or write, beyond my name and some small things. Did Saint Augustine say what the preacher reported of him?"

"That is enough!" snapped Gerbert. "This girl bears out all that has been charged against the accused. The proceedings are in your hands."

"It is my judgment," said Radulfus, "that we should adjourn, and deliberate in private. The witnesses are dismissed. Go home, daughter, and be assured you have told truth, and need trouble not at all what follows, for the truth cannot but be good. Go, all of you, but hold yourselves ready should you be needed again and recalled. And you, Elave..." He sat studying the young man's

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher