![Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice]()

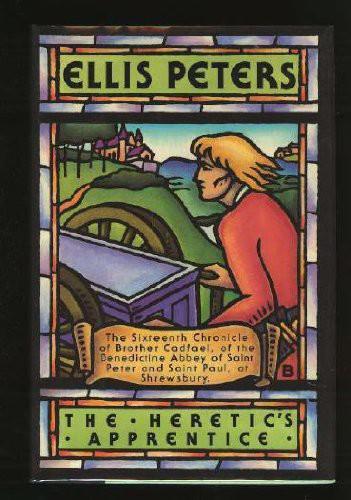

Brother Cadfael 16: The Heretic's Apprentice

with riding in Canon Gerbert's overbearing company. His errand, perhaps, was less pleasurable. So gentle a soul would not enjoy reporting to his bishop an accusation that might threaten a young man's liberty and life, but by his very nature he would probably make as fair a case as he could for the accused. And Roger de Clinton was a man of good repute, devout and charitable if austere, a founder of religious houses and patron of poor priests. All might yet go well for Elave, if he did not let his newly discovered predilection for undisciplined thought run away with him.

I must talk to Anselm about some books for him, Cadfael reminded himself as he left the dusty highroad and began to descend the green path to the riverside, threading the bushes now at the most exuberant of their summer growth, rich cover for fugitives or the beasts of the woodland. The vegetable gardens of the Gaye unfolded green and neat along the riverside, the uncut grass of the bank making a thick emerald barrier between water and tillage. Beyond were the orchards, and then two fields of grain and the disused mill, and after that trees and bushes leaning over the swift, silent currents, crowding an overhanging bank, indented here and there by little coves, where the water lay deceptively innocent and still, lipping sandy shallows. Cadfael wanted comfrey and marsh mallow, both the leaves and the roots, and knew exactly where they grew profusely. Freshly prepared root and leaf of comfrey to heal Elave's broken head, marsh mallow to sooth the surface soreness, were better than the ready-made ointments or the poultices from dried materia in his workshop. Nature was a rich provider in summer. Stored medicines were for the winter.

He had filled his scrip and was on the point of turning back, in no hurry since he had plenty of time before Prime, when his eye caught the pallor of some strange water flower that floated out on the idle current from under the overhanging bushes, and again drifted back, trailing soiled white petals. The tremor of the water overlaid them with shifting points of light as the early sun came through the veil. In a moment they floated out again into full view, and this time they were seen to be joined to a thick pale stem that ended abruptly in something dark.

There were places along this stretch of the river where the Severn sometimes brought in and discarded whatever it had captured higher upstream. In low water, as now, things cast adrift above the bridge were usually picked up at that point. Once past the bridge, they might well drift in anywhere along this stretch. Only in the swollen and turgid floods of winter storms or February thaws did the Severn hurl them on beyond, to fetch up, perhaps, as far downstream as Attingham, or to be trapped deep down in the debris of storms, and never recovered at all. Cadfael knew most of the currents, and knew now from what manner of root this pallid, languid flower grew. The brightness of the morning, opening like a rose as the gossamer cloud parted, seemed instead to darken the promising day.

He put down his scrip in the grass, kilted his habit, and clambered down through the bushes to the shallow water. The river had brought in its drowned man with just enough impetus and at the right angle to lodge him securely under the bank, from drifting off again into the current. He lay sprawled on his face, only the left arm in deep enough water to be moved and cradled by the stream, a lean, stoop-shouldered man in dun-coloured coat and hose, indeed with something dun-coloured about him altogether, as though he had begun life in brighter colours and been faded by the discouragement of time. Grizzled, straggling hair, more grey than brown, draped a balding skull. But the river had not taken him; he had been committed to it with intent. In the back of his coat, just where its ample folds broke the surface of the water, there was a long slit, from the upper end of which a meagre ooze of blood had darkened and corroded the coarse homespun. Where his bowed back rose just clear of the surface, the stain was even drying into a crust along the folds of cloth.

Cadfael stood calf-deep between the body and the river, in case the dead man should be drawn back into the current when disturbed, and turned the corpse face upward, exposing to view the long, despondent, grudging countenance of Girard of Lythwood's clerk, Aldwin.

There was nothing to be done for him. He was sodden and bleached with water,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher