![Buried Prey]()

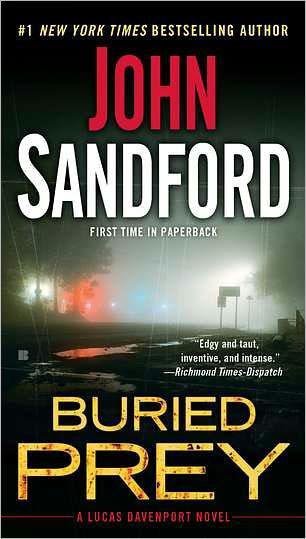

Buried Prey

as he could under the wire.

A narrow dirt trail, no more than a foot wide, led from the slide-under place to the tree. The bluff going down to the river was steep, and he had to hang on to the brush to keep his balance.

The tree was huge, and canted slightly toward the river; the riverside roots were out in the air, and two empty boxes were wedged beneath them to make a cardboard cave. They were covered by a sheet of translucent plastic, like the kind painters used, but heavier. One edge of the plastic had been curled into a pipe that would collect water from the top of the boxes and empty a bit down the slope.

One of the boxes was pushed in horizontally, and was long enough to sleep in. The other was shorter, and upright, but high enough to sit in. The area around the boxes was littered with plastic and paper trash, the remains of magazines and newspapers. A green plastic Bic lighter was tangled in a bush down the slope, apparently discarded. Near the bottom of the slope, he could see tufts of rotting toilet paper around a clump of brush that was probably the man’s toilet.

The water washing under the tree would collect in a shallow gully, and clean up the toilet from time to time, Lucas thought.

So: the boxes.

Not much to see, but he’d have to call it in—maybe there’d be fingerprints or something. He got down on his knees for a better look into the boxes, and noticed a slit in the back of the bed box, and a fold. Like a cupboard, he thought. He wondered briefly if he might get some disease by crawling into the box, then got down, and crawled in.

He could smell the man, even after a month. He tried breathing through his mouth, but it didn’t help much. Well into the box, on his hands and knees, he reached back and pulled open the flap. It had been a cupboard, or something, he thought, a hole carved into the dirt, but it was empty now.

He crawled a bit deeper in and yanked the cardboard flap farther open . . . and saw the edge of several sheets of paper that had slipped down between the box and the dirt wall behind it. He pulled one of the sheets out, and for a moment, with the sheet upside down, didn’t quite understand what he’d found.

He turned it around and said, “Jesus Christ.”

He was holding a pornographic photograph, torn from a badly printed magazine. The woman—girl—in the photo was either very young, or looked very young. She was sitting astride a man, her head thrown back, the man’s penis visibly penetrating her.

Lucas put the paper on the floor of the box and carefully backed out.

He dusted off his hands, noticed that they were shaking a little: adrenaline.

“Jesus Christ,” he said again. And: he’d found something. He’d investigated, and he’d come up with something important, on his own. The rush was like kicking Wisconsin in hockey.

He hurried back to the hole in the fence, slipped under, got his jacket off the bush, and half ran back to the Proses’ house. He knocked and Prose came to the door, now wearing a bathrobe, and Lucas said, “I need to use your phone. And talk to your wife. Like right now.”

HE CALLED DANIEL at home. Daniel came up and said, “Davenport? It can’t wait for breakfast?”

“I don’t think so,” Lucas said. “I found where that street guy was staying. He had a stash of porn, with some really young women in it. Like, girls. Young girls.”

“Where are you?” Daniel asked.

Lucas gave him the address, and Daniel said, “I’ll be there in fifteen minutes. You sit on that site, don’t let anybody get close to it. You got that? You sit on it.”

“I’ll sit on it,” Lucas said.

He actually sat on the Proses’ front porch, talking to Alice Prose, a tall sandy-haired woman who looked like she should have been an English school mistress, and he drank a glass of the Proses’ orange juice. Alice gave him a thorough description of the street guy: tall, not old but with a burned, weather-wrinkled face, brown and gray hair down to the back of his neck, a full beard. He wore a baseball hat, with a logo above the bill, but she’d never been close enough to see what the logo was. He carried a nylon backpack, stuffed with clothes or bedding. There was the occasional odor of cooking food around the tree, and sometimes a fecal odor, “which is one reason that people thought it was best if he’d find someplace else to stay. Someplace with a bathroom,” she said.

She’d never seen him with anybody else, male or female. “He

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher