![Burning the Page: The eBook revolution and the future of reading]()

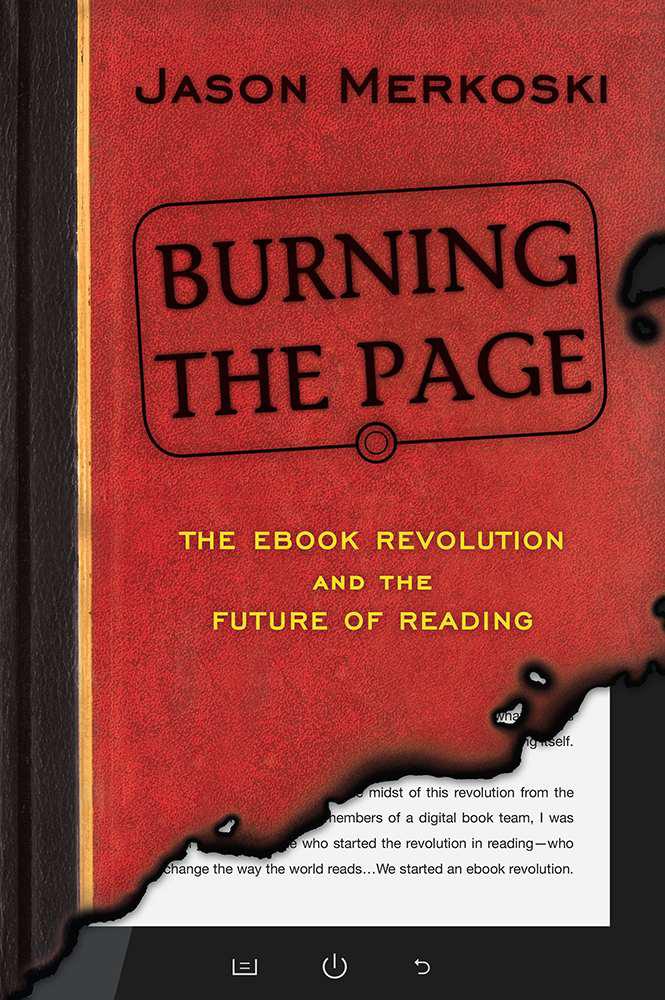

Burning the Page: The eBook revolution and the future of reading

from handwritten to print.

The ebook is the second wave in the original print revolution. And this second wave is larger than the original wave that Gutenberg ushered in. It’s a wave that has the ability to bring everything together, if it’s done well. As experiential products, ebooks are able to contain images and video and audio and games and social network conversations—something that print books can’t hope to accomplish.

Not only that, but this second wave in reading can also bring down cultural barriers, like language itself. In the ultimate imagining of ebooks, it will be possible for one book to be rendered into many languages automatically. Likewise, all the comments will be automatically translated into the same language, allowing you and someone in Egypt or Spain to converse as book lovers while reading the same book, without worrying about language barriers.

But we need good language-translation services first.

Globally, there are about 6,900 living languages and at least that many unique ways of seeing the world.

Languages are puzzle boxes. What we do when we speak expresses only a hundredth of what we actually think. We leap from idea to idea with barely a thought, but we only express one idea of the many we conceive. That’s what makes conversations so much fun, and books too. They are all about translating, interpreting, discovering, and creating meanings from these puzzle boxes.

The difference is that languages aren’t antiques, like dusty, inlaid Chinese boxes with sliding panels. They’re made fresh every minute with every new utterance and usage, and they have to be deciphered anew at every sentence. So much is unsaid in a sentence that it has to be puzzled out and reconstructed. The process can often go awry, maybe because the speaker was joking, or using puns or double entendres, or perhaps because the listener misinterpreted what he or she read or heard.

Given all that can go wrong in communicating a sentence, let alone an entire book, it’s a wonder that books are translated at all.

And in fact, no translation is perfect. Any skilled translator will perform a deep reading of the book and try to interpret it before rewriting it anew. Inevitably, though—and this is part of the charm of translations—different nuances are brought to bear on the final translation because each translator interprets the book differently. Each translator implicitly refracts the book’s meaning through the crystal of his or her own life.

Some translations are more widely read than the originals and have a greater cultural impact. For example, between 1604 and 1611, the original Bible was translated into the English common at the time of Shakespeare. Named the King James Bible, after the then-current king of England, it abounds with terms we still use—turns of phrase such as “a broken heart” or “a drop in the bucket” or even “bite the dust” —but these, of course, never appeared as such in the original Greek and Latin.

This version of the Bible influenced writers from John Milton to William Faulkner. The text of the King James Bible was carefully crafted word by word by a committee of unpaid but highly devoted scholars who worked on this as a “labor of love.” They were men who perhaps never “saw eye to eye” but who “went the extra mile” to phrase the Bible in simple, easygoing speech.

But we’re in a digital world now. Since 2009, more books have been self-published every year than published by traditional publishers. In 2011 alone, almost 150,000 new self-published books glutted the marketplace, according to Bowker, a U.S. book trade organization. This is far more books than can conceivably be translated by humans. We shouldn’t have to rely on translators, right? Perhaps we’re sophisticated enough now that this can be automated and done digitally.

Google, for example, already offers a way to translate a given ebook into the language of your choice. I wanted to see how accurate automatic book-translation could be, so as an experiment, I took a paragraph from this chapter and used Google’s translator service to render it into another language (say, Chinese) and then re-translate it back into English. For example, when I translated “Languages are puzzle boxes” into Chinese and back to English, I got “Languages are mystery boxes, old conundrum boxes.” To determine the success rate, I took the number of correct words and subtracted it from the total

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher