![By Murder's bright Light]()

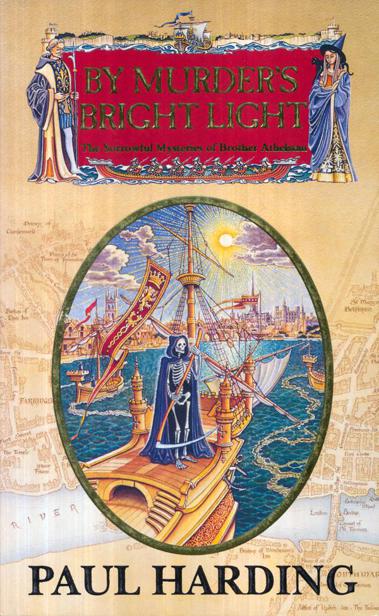

By Murder's bright Light

the deck, jarring his arm. The Frenchman lifted his sword to strike but he must have realised Athelstan was a priest, for he smiled, stepped back and disappeared into the throng. The friar, nursing his bruised arm, limped towards the cabin. Behind him, he could hear Cranston ’s roar. The friar closed his eyes and prayed that Christ would protect the fat coroner. Then he heard the bray of a trumpet, once, twice, three times, and immediately the fighting began to slacken. The arrows ceased to fall, shouted orders faltered. Athelstan, resting against the cabin, glanced along the ship, experiencing that eerie silence which always falls as a battle ends. Even the wounded and dying ceased their screaming.

‘Are you all right, Brother?’

Cranston came swaggering across the deck. The coroner was splashed with blood, his sword still wet and sticky. He appeared unhurt except for a few scratches on his hand and a small flesh wound just beneath his elbow. Cranston grasped Athelstan by the shoulder and pushed his face close, his ice-blue eyes full of concern.

‘Athelstan, you are all right?’

‘Christ be thanked, yes I am!’

‘Good!’ Cranston grinned. ‘The farting Frenchmen have gone!’ The coroner turned, legs spread, big belly and chest stuck out, and raised his sword in the air. ‘We beat the bastards, lads!’

Cheering broke out and Athelstan could hear it being taken up on the cogs further down the line. He walked to the ship’s side. A number of French galleys were on fire and now lay low in the water, the roaring flames turning them to floating cinders. Of Eustace the Monk’s own galley and the rest of his small pirate fleet there was no sign.

“What will happen now, Sir John?’ Athelstan asked.

The buggers will race for the sea,’ the coroner replied. They have to be out before dawn, when this mist lifts.’

Cranston threw his sword on the deck, his attention caught by the cries of a group of men under the mast. Cranston and Athelstan crossed to where Sir Jacob Crawley lay, a surgeon crouched over him tending a wound in his shoulder. The admiral winced with pain as he grabbed Cranston ’s hand.

‘We did it, Jack.’ The admiral’s face, white as a sheet, broke into a thin smile. ‘We did it again, Jack, like the old days.’

Cranston looked at the surgeon.

‘Is he in any danger?’

‘No,’ the fellow replied. ‘Nothing a fresh poultice and a good bandage can’t deal with.’

Crawley struggled to concentrate. He peered at Athelstan.

‘I know,’ he whispered. ‘I remember. Everything was so tidy, so very, very tidy!’ Then he fell into a swoon.

Athelstan and Cranston drew away. The ship became a hive of activity and the friar winced as the archers, using their misericorde daggers, cut the throats of the enemy wounded and unceremoniously tossed their corpses into the river. Boats were lowered and messages sent to the other ships about what was to be done with the English wounded, the dead of both sides and the enemy prisoners.

Athelstan, nursing his arm, sat in the cabin and listened as Cranston , between generous slurps from his wineskin, gave a graphic description of the fight. Crawley , now being sent ashore to the hospital at St Bartholomew’s, had won a remarkable victory. Four galleys had been sunk and a number of prisoners taken. Most of these, perhaps the luckiest, were already on their way to the flagship to be hanged.

The news had by now reached the city. Through the fog came the sound of bells and sailors reported that, despite the darkness and the mist, crowds were beginning to gather along the quayside.

‘Sir John,’ Athelstan murmured. ‘We should go ashore. We have done all we can here.’

Cranston , who was preparing for a third description of his masterly prowess, rubbed his eyes and smiled.

‘You are right.’

The coroner walked to the cabin door and watched as a French prisoner, a noose tied around his neck, was pushed over the side to die a slow, choking death.

‘You are right, Brother, we should go. No charging knights, no silken-caparisoned destriers, just a bloody mess and violent death.’

They crossed the deck to the shouts and acclamations of the sailors and archers. Athelstan glimpsed the dangling corpses.

‘Sir John, can’t that be stopped?’

‘Rules of war,’ Cranston replied. ‘Rules of war. Eustace the Monk is a pirate. Pirates are hanged out of hand.’

Crawley ’s lieutenant had the ship’s boat ready for them. Cranston

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher