![Cyberpunk]()

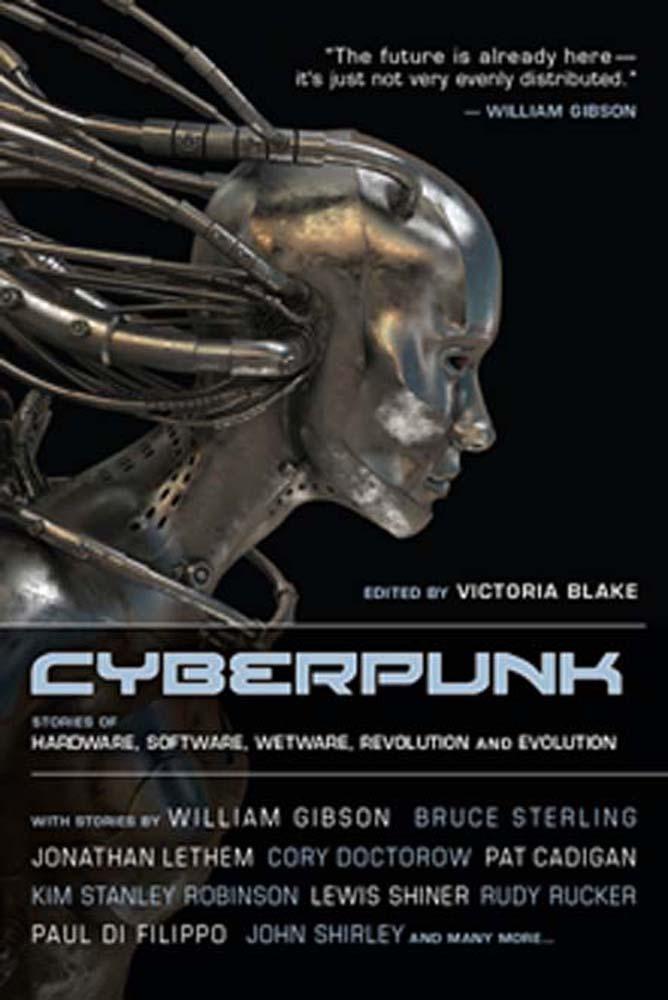

Cyberpunk

protesters cheered crazily. Lee watched them as they danced around the sling after a successful shot. He approached some of the calmer seated spectators.

“Want to buy a joint?”

“How much?”

“Five dollars.”

“Too much, man! You must be kidding! How about a dollar?”

Lee walked on.

“Hey, wait! One joint, then. Five dollars . . . shit.”

“Going rate, man.”

The protester pushed long blond hair out of his eyes and pulled a five from a thick clip of bills. Lee got the battered Marlboro box from his pocket and took the smallest joint from it. “Here you go. Have fun. Why don’t you fire one of them paint bombs at those tanks, huh?”

The kids on the ground laughed. “We will when you get them stoned!”

He walked on. Only five joints left. It took him less than an hour to sell them. That meant thirty dollars, but that was it. Nothing left to sell. As he left the Mall he looked back at the monument; under its wash of paint it looked like a bone sticking out of raw flesh.

Anxious about coming to the end of his supply, Lee hoofed it up to Dupont Circle and sat on the perimeter bench in the shade of one of the big trees, footsore and hot. In the muggy air it was hard to catch his breath. He ran the water from the drinking fountain over his hands until someone got in line for a drink. He crossed the circle, giving a wide berth to a bunch of lawyers in long-sleeved shirts and loosened ties, lunching on wine and cheese under the watchful eye of their bodyguard. On the other side of the park, Delmont Briggs sat by his cup, almost asleep, his sign propped on his lap. The wasted man. Delmont’s sign—and a little side business—provided him with just enough money to get by on the street. The sign, a battered square of cardboard, said PLEASE HELP—HUNGRY. People still looked through Delmont like he wasn’t there, but every once in a while it got to somebody. Lee shook his head distastefully at the idea.

“Delmont, you know any weed I can buy? I need a finger baggie for twenty.”

“Not so easy to do, Robbie.” Delmont hemmed and hawed and they dickered for a while, then he sent Lee over to Jim Johnson, who made the sale under a cheery exchange of the day’s news, over by the chess tables. After that Lee bought a pack of cigarettes in a liquor store and went up to the little triangular park between 17th, S, and New Hampshire, where no police or strangers ever came. They called it Fish Park for the incongruous cement whale sitting by one of the trash cans. He sat down on the long broken bench, among his acquaintances who were hanging out there, and fended them off while he carefully emptied the Marlboros, cut some tobacco into the weed, and refilled the cigarette papers with the new mix. With their ends twisted he had a dozen more joints. They smoked one and he sold two more for a dollar each before he got out of the park.

But he was still anxious, and since it was the hottest part of the day and few people were about, he decided to visit his plants. He knew it would be at least a week till harvest, but he wanted to see them. Anyway, it was about watering day.

East between 16th and 15th he hit no-man’s-land. The mixed neighborhood of fortress apartments and burned-out hulks gave way to a block or two of entirely abandoned buildings. Here the police had been at work, and looters had finished the job. The buildings were battered and burnt out, their ground floors blasted wide open, some of them collapsed entirely into heaps of rubble. No one walked the broken sidewalk; sirens a few blocks off and the distant hum of traffic were the only signs that the whole city wasn’t just like this. Little jumps in the corner of his eye were no more than that; nothing there when he looked directly. The first time, Lee had found walking down the abandoned street nerve-racking; now he was reassured by the silence, the stillness, the no-man’s-land smell of torn asphalt and wet charcoal, the wavering streetscape empty under a sour-milk sky.

• • •

His first building was a corner brownstone, blackened on the street sides, all its windows and doors gone, but otherwise sound. He walked past it without stopping, turned, and surveyed the neighborhood. No movement anywhere. He stepped up the steps and through the doorway, being careful to make no footprints in the mud behind the doorjamb. Another glance outside, then up the broken stairs to the second floor. The second floor was a jumble of beams and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher