![Dreaming of the Bones]()

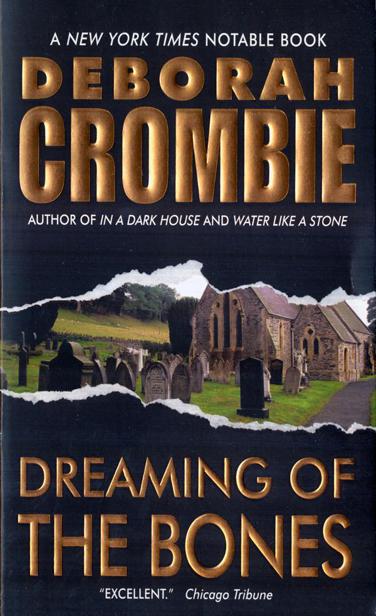

Dreaming of the Bones

deep-set eyes were blue.

He studied her with his usual wariness, then he shrugged and said, ”A little mishap with a car. He’s in hospital.” His voice was surprisingly deep, and his accent suggested he was well educated.

”Oh. Is he going to be all right? Can you manage...” Her spontaneous offer of help faltered under his stare. ”I mean...”

But he said politely enough, ”A few cracked ribs. And yes, I can manage, thank you.”

”Oh, good. It’s good that he’s not hurt too badly, I mean,” said Gemma, feeling more of an idiot by the minute, but she couldn’t resist one last curious question. ”What’s your name?”

She thought he wouldn’t answer, but after a moment he said reluctantly, ”Gordon.”

”I’m Gemma.” When there seemed to be nothing else to say, she added awkwardly, ”Well, cheerio, then,” and turned away.

She glanced back, once, and saw him lift the clarinet to his lips. The music followed her as she turned west into Richmond Avenue , fading until the last faint notes might have been her imagination.

The damp and dreary weather of the past few days had cleared during the afternoon, and as she neared Thornhill Gardens , pale pink as uniform as a bedsheet spread itself across the sky, then darkened slowly to rose. Against this backdrop the Georgian houses took on a dark and calming geometry, and by the time Gemma reached her flat she felt a bit more able to adjust herself to what she thought of as the other side of her schizophrenic life.

She found Hazel on the patio, watching the last of the sunset while the children played in the garden. When she’d hugged Toby, she sank into the chair beside Hazel and sighed.

The small table between them held a bottle of sherry and two glasses, and Hazel filled the empty glass and handed it to Gemma. ”Cheers,” she said, raising her glass. ”It sounds as though you’ve had a long day.” She pulled her bulky cardigan a little closer round her throat and took a sip of her drink. ”I couldn’t bear to go inside quite yet. The children have had their tea, but not their baths.”

”Wouldn’t have done much good, would it?” said Gemma, as the children were digging happily in the muddy spot beneath the rosebush. ”I’ll bathe them in a bit.” She leaned back into the cold curve of the wrought iron chair and closed her eyes. It would do her good to watch the children play in the tub, and to hold their warm and slippery bodies as she toweled them dry.

The thought of hugging Toby brought with it the image she’d been resisting all day—Vic standing on her porch, laughing, with her arm round her son’s shoulders—and with it the fear that Gemma hated to acknowledge even to herself. What would happen to Toby if she died? His father, like Kit’s, was out of the picture, and just as well, for he’d certainly shown no aptitude for parenting, nor any interest in his son. She supposed her parents would take Toby, and that he would be loved and cared for, but it would not be the same. Or did she just want to think she was irreplaceable?

Hazel reached over and patted her arm. ”Tell me about it.”

”Oh, sorry,” Gemma said, startled. ”I was just thinking.”

”Obviously. Your eyebrows were about to meet.”

Gemma smiled at that, but then asked slowly, ”Are we really indispensable to our children, Hazel? Or do they go on quite happily without us, once the initial grief has passed?”

Hazel gave her a swift glance before answering. ”Child psychology experts will tell you all sorts of complicated things about bereaved children suffering from an inability to trust or form relationships, but to tell you the truth, I just don’t know. Some do perfectly well, and some don’t. It depends on the mother, and the child, and the caretakers, and those are just too many variables to allow one to make accurate predictions.” She took a sip of her drink and added, ”You’re worrying about Vic’s son, aren’t you?”

”What’s happened to him is so dreadful it just doesn’t bear thinking of, but I keep thinking of it.”

”And I take it today’s news is not good?” said Hazel. Gemma shook her head. ”No. It looks as though she was poisoned.” She went on to tell Hazel about Kincaid’s decision to take a leave of absence, and of her fears for him. ”He won’t listen to me, Hazel. He’s so stubborn, and so angry. He’s even angry with me, and I don’t know what I’ve done or how I can reach him.”

”If

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher