![Dreaming of the Bones]()

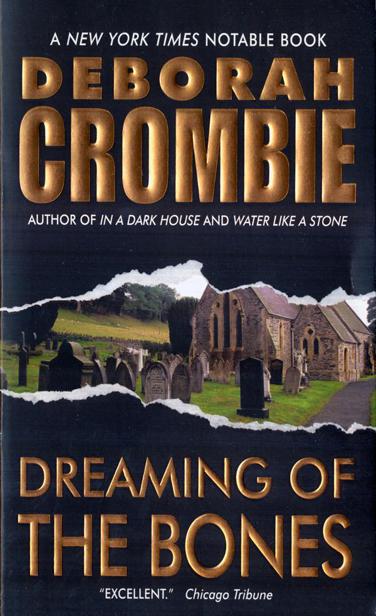

Dreaming of the Bones

I were you, I’d give him a day or two, let him start sorting it out on his own. And I suspect that his anger is due to more than the circumstances of Vic’s death. Men often substitute anger for grief, because anger is the only emotion they’re taught it’s acceptable to feel. I don’t know what else you can do, love, because I doubt very much you’re going to change his mind about this.”

”The awful thing is that I understand how he feels, because I feel responsible, too,” said Gemma. ”I thought Vic had legitimate cause to be uneasy about Lydia Brooke’s death, but I didn’t encourage Duncan to look into it any further.” She made a grimace of disgust, adding, ”I didn’t want it to take his time away from me.”

”And you think that Vic’s death must be connected to her suspicions about Lydia’s death?” asked Hazel.

Shrugging, Gemma said, ”It’s certainly possible. Unless someone knew enough about what Vic was doing to take advantage of it as camouflage.” She shivered. It was now almost fully dark, and the temperature in the garden had dropped. ”But Lydia is as good a place to start as any. I wish I’d had a look at those things of Vic’s...”

”Didn’t you tell me that Lydia was fascinated with Rupert Brooke?”

”Yes, but I’m afraid I don’t know much about him, other than the golden young Edwardian poet stuff, and, ‘If i should die, think only this of me...’ We had to memorize it at school, and I remember thinking it was bloody stupid.” Gemma looked at the children, who had moved to the edge of the flagstones and were giggling while doing something unspeakable to one of Holly’s dolls. ”I hope Toby will have more sense.”

”Men,” said Hazel, and they smiled at each other in tacit understanding. ”Well, if you’re interested in Rupert Brooke, I’ve some things you might like to see. Because you’re not going to let Duncan do this on his own, are you, love?”

Gemma hadn’t made a conscious decision, but as soon as Hazel spoke she knew it to be true, and inevitable. ”No,” she said. ”I suppose I’m not.”

After the children had been bathed, and Gemma had sat down to a vegetable lasagna with Tim and Hazel, Hazel left Tim with the dishes and led Gemma into the sitting room. Glass-fronted bookcases lined the walls either side of the fireplace, and Hazel studied them for a minute, her finger against her nose, before going to the right-hand case.

”I think I put them all together, but it’s been ages since I’ve looked at them, and the children will get into the books.” Hazel opened the case and bent down to survey the spines. ”Ah, here they are.” Removing a few volumes, she carried them to the sofa, and Gemma sat down beside her. ”I had rather a thing for Rupert myself at one time, so I can sympathize with Lydia’s infatuation. Rupert Chawner Brooke, born 1887, son of a Rugby master,” Hazel recited from memory, grinning.

She handed the first book to Gemma. ”I’ve only a paperback of Marsh’s Memoir, I’m afraid, picked up at an Oxfam bookshop, but the contemporary introduction is worth reading, and it does contain all the poems.” Frowning, she added, ”But these others Lydia wouldn’t have known when she was at college. The Hassall biography was published in 1964, the Letters in sixty-eight. And the collection of his love letters to Noel Olivier was released only a few years ago. Vic would have been familiar with all of these, though, I’m sure.”

”Who was Noel Olivier?” asked Gemma. ”Any relation to Laurence?”

”The youngest of the four Olivier sisters, and I think they were cousins to Laurence,” explained Hazel. ”Rupert met her when she was fifteen and he was twenty, and he was smitten with her for years. They remained friends and correspondents until he died.”

Accepting each volume as Hazel handed it across, Gemma wondered what she had got herself into. She studied the black-and-white photo of Brooke on the cover of the Memoir, with his tumbled hair and penetrating gaze. ”He was quite stunningly beautiful, wasn’t he? I wondered why everyone was so besotted with him.”

”Yes, his looks were rather spectacular,” Hazel admitted. ”But I doubt his looks alone would have generated such interest decades after his death. To me, he represents a slaughtered generation, a loss of innocence of a magnitude unimaginable before the Great War.”

”He was killed in the war, wasn’t

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher