![Empty Mansions]()

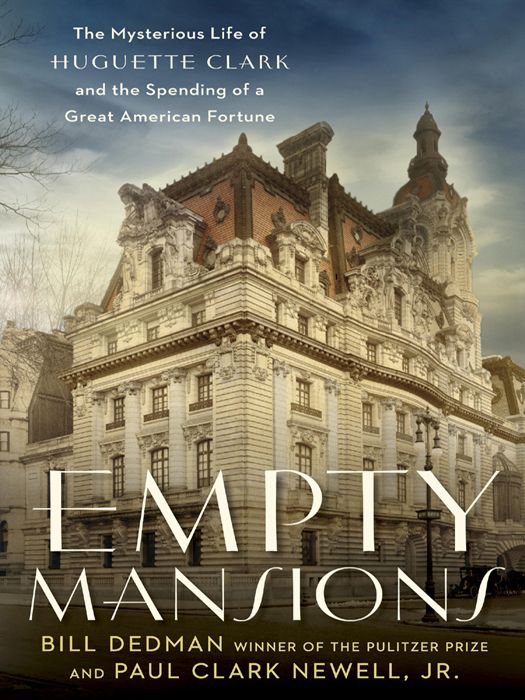

Empty Mansions

studios of Monet and Van Gogh for pocket change.

W.A. made a splashy entrance into New York society as an art buyer in 1898, paying an extravagant price for a Fortuny painting,

The Choice of a Model

. The subject of this kitschy work is a nude woman posing before an assemblage of male artists. W.A.’s purse strings could be loosened by female pulchritude. He paid $42,000, a record price for a painting, which commanded New York’s attention: Who

was

this westerner?

To advise him on his collection,W.A. had been induced to hire Joseph Duveen, a shrewd British purveyor of fine art to American millionaires. To get the commission, Duveen somehow learned details of Clark’s house plans and spent $20,000 on a model of the manse—a dollhouse based on the Clark home. This plaster model was accurate down to the carpets, tapestries, and light fixtures—all to be purchased from Duveen.

Duveen’s taste was impeccable and his contacts superb, but his ethics questionable. Among the pieces he located was the

Hope Venus

, which was available for $25,000. A Parisian dealer persuaded Duveen that this was not a sufficiently important price to interest Clark, who had spread the word that he wanted the best in the market. Duveen raised the price to $110,000, and Clark bought it.

• • •

As guests toured the Clark collection on Saturday afternoons, the main attraction was not any particular piece of art, but the music one heard throughout the galleries. The music came from an enormous pipe organset into the wall above the entrance to a picture gallery. It wasthe finest organ anyone ever thought of putting in a private home. It was the size of organs at metropolitan churches, with 4,496 pipes encased in a grill-work of oak. Hidden ducts carried the sound to the art galleries, enveloping visitors with music.

One of the five art galleries in the Clark mansion was dominated by a wall of pipes belonging to the $120,000 organ, which filled all the galleries with music.

( illustration credit 4.1 )

The original price of the organ was $50,000, but W.A. demanded the most wonderful chamber organ in the world, driving the cost up to $120,000, or roughly $3 million today. Critics declared its sound “the most perfect ever heard,” and on one occasion two hundred members of theMormon Tabernacle Choir stood in W.A.’s gallery to sing. He and Anna hiredtheir own church organist, and he stayed on staff, well salaried, for the next fourteen years.

A DAMNABLE CONSPIRACY

W.A.’ S QUEST FOR SOCIAL ACCEPTANCE could have overcome the obstacles of a shy wife with no social ambitions, even the lack of a marriage certificate. His campaign was thwarted, however, by the stain from his messy political career.

One political cartoon of the early 1900s showed W. A. Clark firing a cannon in battle—with bags of money used as ammunition at the rate of a thousand dollars a second. Another showed W.A. working in a barn as “the new chore boy,” feeding not corn but millions of dollars to a raggedy mule named Democracy. A third depicted W.A. as a stray cat with dollar signs for eyes—a cat that keeps returning to the door of the U.S. Senate.

W.A.’s public profile was summed up, or solidified, by Mark Twain, coiner of the derisive term “the Gilded Age” and the principal American voice of the era. In an essay penned in 1907, Twain excoriated W. A. Clark of Montana. “He is said to have bought legislatures and judges as other men buy food and raiment. By his example he has so excused and so sweetened corruption that in Montana it no longer has an offensive smell.”

Twain was just getting started. “His history is known to everybody; he is as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag; he is a shame to the American nation, and no one has helped to send him to the Senate who did not know that his proper place was the penitentiary, with a chain and ball on his legs.”

There was a personal connection between Mark Twain and W. A. Clark, which the author did not disclose.

• • •

W. A. Clark’s desire in the last twenty years of the nineteenth century was a title, and his quest made him nearly a permanent political candidate in the first days of the state of Montana, which denied him the honortime after time. He presided over two conventions that wrote constitutions for the new state, supporting the vote for women and immigrants while leading the opposition to taxation of mines. But that wasn’t enough for W.A.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher