![Fatherland]()

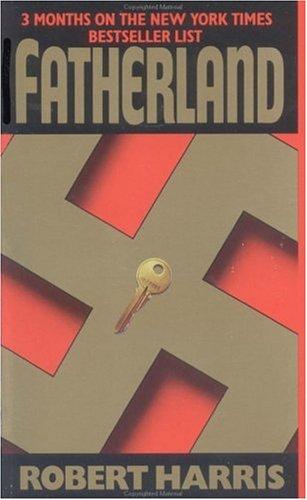

Fatherland

onto a stage against his will. Wearing his new Pimpf uniform—crisp black shirt and dark blue shorts—he had climbed wordlessly into the car. March had given him an awkward hug.

"You look smart. How's school?"

"All right."

"And your mother?"

The boy shrugged.

"What would you like to do?"

He shrugged again.

They had lunch in Budapester-Strasse, opposite the zoo, in a modern place with vinyl seats and a plastic-topped table: father and son, one with beer and sausages, the other with apple juice and a hamburger. They talked about the Pimpfen and Pili brightened. Until you were a Pimpf you were nothing, "a nonuniformed creature who has never participated in a group meeting or a route march." You were allowed to join when you were ten and stayed until you were fourteen, when you passed into the full Hitler Youth.

"I was top in the initiation test."

"Good lad."

"You have to run sixty meters in twelve seconds," said Pili. "Do the long jump and the shot put. There's a route march—a day and a half. Written stuff. Party philosophy. And you have to recite the 'Horst Wessel Lied.' "

For a moment, March thought he was about to break into song. He cut in hurriedly, "And your dagger?"

Pili fumbled in his pocket, a crease of concentration on his forehead. How like his mother he is, thought March. The same wide cheekbones and full mouth, the same serious brown eyes set far apart. Pili laid the dagger carefully on the table before him. He picked it up. It reminded him of the day he had gotten his own—when was it? '34? The excitement of a boy who believes he's been admitted to the company of men. He turned it over and the swastika on the hilt glinted in the light. He felt the weight of it in his hand, then gave it back.

"I'm proud of you," he lied. "What do you want to do? We can go to the cinema. Or the zoo."

"I want to go on the bus."

"But we did that last time. And the time before."

"Don't care. I want to go on the bus."

"The Great Hall of the Reich is the largest building in the world. It rises to a height of more than a quarter of a kilometer, and on certain days—observe today—the top of its dome is lost from view. The dome itself is one hundred and forty meters in diameter, and St. Peter's in Rome will fit into it sixteen times."

They had reached the top of the Avenue of Victory and were entering Adolf-Hitler-Platz. To the left, the square was bounded by the headquarters of the Wehrmacht High Command, to the right by the new Reich Chancellery and Palace of the Führer. Ahead was the hall. Its grayness had dissolved as their distance from it had diminished. Now they could see what the guide was telling them: that the pillars supporting the frontage were of red granite, mined in Sweden, flanked at either end by golden statues of Atlas and Tellus, bearing on their shoulders spheres depicting the heavens and the earth.

The building was as crystal white as a wedding cake, its dome of beaten copper a dull green. Pili was still at the front of the coach.

"The Great Hall is used only for the most solemn ceremonies of the German Reich and has a capacity of one hundred and eighty thousand people. One interesting and unforeseen phenomenon: the breath from this number of humans rises into the cupola and forms clouds, which condense and fall as light rain. The Great Hall is the only building in the world that generates its own climate ..."

March had heard it all before. He looked out of the window and saw the body in the mud. Swimming trunks! What had the old man been thinking of, swimming on Monday night? Berlin had been blanketed by black clouds from late afternoon. When the storm had finally broken, the rain had descended in steel rods, drilling the streets and roofs, drowning the thunder. Suicide, perhaps? Think of it. Wade into the cold lake, strike out for the center, tread water in the darkness, watch the lightning over the trees, wait for tiredness to do the rest. . .

Pili had returned to his seat and was bouncing up and down in excitement. "Are we going to see the Führer, Papa?"

The vision evaporated and March felt guilty. This daydreaming was what Klara used to complain of: " Even when you're here, you're not really here. ... "

He said, "I don't think so."

The guide again: "On the right is the Reich Chancellery and residence of the Führer. Its total facade measures exactly seven hundred meters, exceeding by one hundred meters the façade of Louis XIV's palace at Versailles."

The Chancellery

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher