![Fatherland]()

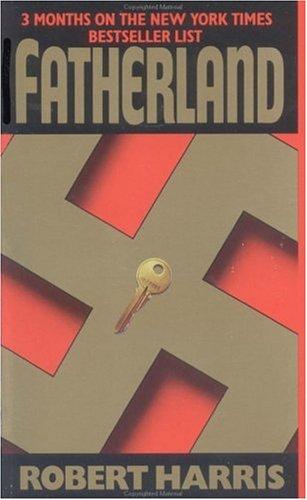

Fatherland

couple of Sipo guys were around at the archive last week asking about you."

Nebe again: "There's a complaint here from your ex-wife; even one from your son."

He walked for half an hour along the blossoming streets, past the high hedges and picket fences of prosperous suburban Berlin. When he reached Dahlem, he stopped a student to ask directions. At the sight of March's uniform, the young man bowed his head. Dahlem was a student quarter. The male undergraduates, like this one, let their hair grow a few centimeters over their collars; some of the women wore jeans—God only knew where they got them. White Rose, the student resistance movement that had flowered briefly in the 1940s until its leaders were executed, was suddenly alive again, "lhr Geist lebt weiter" said the graffiti: Their spirit lives on. Members of White Rose grumbled about conscription, listened to banned music, circulated seditious magazines, were harassed by the Gestapo.

The student, his arms laden with books, gestured vaguely in response to March's question and was glad to be on his way.

Luther's house was close to the Botanischer Garten, set back from the road—a nineteenth-century country mansion at the end of a sickle of white gravel. Two men sat in an unmarked gray BMW, parked opposite the drive. The car and its color branded them at once. There would be two more watching the back, and at least one cruising the neighborhood streets. March walked past and saw one of the Gestapo watchers turn to the other and speak.

Somewhere a lawn mower was whining; the smell of freshly cut grass hung over the drive. The house and grounds must have cost a fortune—not as much as Buhler's villa, perhaps, but not far off. The red box of a newly installed burglar alarm jutted beneath the eaves.

He rang the bell and felt himself come under inspection through the spy hole in the center of the heavy door. After half a minute the door opened to reveal an English maid in a black-and-white uniform. He gave her his ID and she disappeared to check with her mistress, her feet flapping on the polished wooden floor. She returned to show March into the darkened drawing room. A sweet-smelling smog of eau de cologne lay over the scene. Frau Marthe Luther sat on a sofa, clutching a handkerchief. She looked up at him—glassy blue eyes cracked by minute veins.

"What news?"

"None, madam, I'm sorry to say. But you may be sure that no effort is being spared to find your husband." Truer than you know, he thought.

She was a woman fast losing her attractiveness, but gamely staging a fighting retreat. Her tactics, though, were ill advised: unnaturally blond hair, a tight skirt, a silk blouse undone just a button too far to display fat, milky white cleavage. She looked every centimeter a third wife. A romantic novel lay open, facedown, on the embroidered cushion next to her: The Kaiser's Ball by Barbara Cartland.

She returned his identity card and blew her nose. "Will you sit down? You look exhausted. Not even time to shave! Some coffee? Sherry, perhaps? No? Rose, bring coffee for the Herr Sturmbannführer. And perhaps I might fortify myself with just the smallest sherry."

Perched uneasily on the edge of a deep chintz-covered armchair, his notebook open on his knee, March listened to Frau Luther's woeful tale. Her husband? A very good man, short tempered—yes, maybe, but that was his nerves, poor thing. Poor, poor thing—he had weepy eyes, did March know that?

She showed him a photograph: Luther at some Mediterranean resort, absurd in a pair of shorts, scowling, his eyes swollen behind the thick glasses.

On she went: a man of that age—he would be sixty- nine in December, they were going to Spain for his birthday. Martin was a friend of General Franco—a dear little man, had March ever met him?

No: a pleasure denied.

Ah, well. She couldn't bear to think what might have happened, always so careful about telling her where he was going, he had never done anything like this. It was such a help to talk, so sympathetic . . .

There was a sigh of silk as she crossed her legs, the skirt rising provocatively above a plump knee. The maid reappeared and set down a coffee cup, cream jug and sugar bowl in front of March. Her mistress was provided with a glass of sherry and a crystal decanter, three quarters empty.

"Did you ever hear him mention the name Josef Buhler or Wilhelm Stuckart?"

A little crack of concentration appeared in the cake of makeup: "No, I don't recall. . . .

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher