![Here She Lies]()

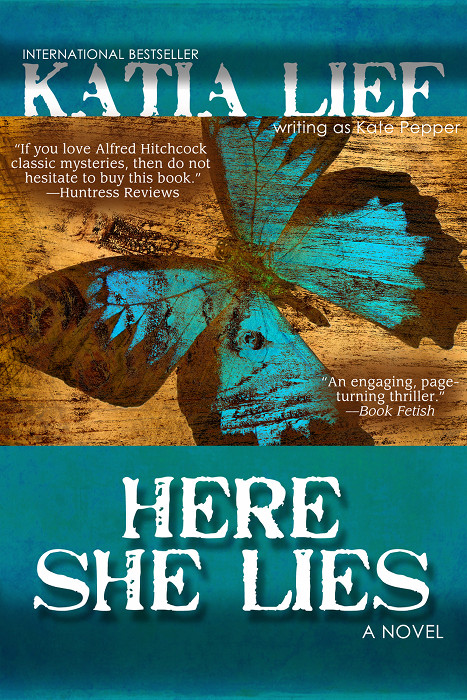

Here She Lies

misapprehension — helpless and very hurt. I had hurt him. I had brought all this on by storming out of our life and coming here. I wanted to touch him, but it would send the wrong message. I hadn’t changed my mind about what had propelled me here in the first place.

“Just so you know, Bobby, I did see what you saw last night. I knew something was wrong because of all the police, but I still saw what you saw and thought what you thought. I felt that horror you felt when I saw her lying there. Except I thought I was looking at Julie.”

He leaned into me on the couch, his left side warm against my right. My body wanted to melt into his, find comfort and healing the easy way. But we had already tried that at home, using sex to settle the argument, and it had never worked for more than a few hours. By morning, my brain would wake up, my eyes would open.

“Here,” I said, handing Lexy to him. “Could you please burp her?” He got up and paced the floor with Lexy over his shoulder, gently patting the spot on her little back. He was a good father; you had to give him that.

“What did Lazare want this morning?” he asked, kissing the side of Lexy’s head.

I pulled the fax out of my pocket and unfolded it. “Did you ever hear anyone at the prison mention Thomas Soiffer?”

Bobby took the crushed paper and looked it over. “Who is he?”

“A neighbor saw him lurking around outside the house yesterday,” I said. “Well, not lurking. Sitting in his van — but for hours.”

He dropped the fax on the coffee table, on top of yesterday’s newspaper, and kept moving, patting and bouncing Lexy. “If they knew about this guy, why did he put so much time into me? He kept me for hours.”

“The neighbor didn’t remember the van until this morning. That’s when the detective found out, too.”

“So last night I was the best thing they had?”

“He said they never get cases like this. They probably don’t know what they’re doing. So what kind of questions did he ask you?”

“We went over every minute of yesterday, every second, over and over and over.” He chanted those last words “over and over and over” as he bounced Lexy in the air in front of him, the way she liked. He angled her side to side, eliciting happy squeals. Then he sang a stanza from Dylan’s “Just Like a Woman,” which his parents had sung to him as a lullaby when he was small. Bobby’s parents had been hippies, and though he had rebelled early against their peripatetic, underfunded lifestyle (rebellion by bank account), their bohemianism had peppered his inner life. His social consciousness may have come from them — he was astrong advocate of prisoners’ rights, as liberal a liberal as you’re likely to find — but his stalwart, conservative sense of stability came from himself.

Lexy burped, and I said, “Why don’t you put her down now? She hasn’t had any floor time since yesterday morning.”

He set her on her stomach on the carpet. I picked up her favorite teether — a sticky red rubbery duck — from the coffee table and put it in front of her. She grabbed it and stuck it in her mouth. Bobby sat down next to me again and reached for my hand, which I pulled away. He smelled so good; I missed him. But it was too soon.

Julie walked into the living room and stopped when she saw us. She seemed a little startled, realizing she had interrupted our awkward reunion.

“Jules,” I said, “would you mind watching Lexy for a few minutes?”

“I’d love to.” Julie picked Lexy up from the floor and held her high, earning smiles and a cackling little laugh.

Bobby followed me through the French doors into the backyard. The overcast morning cast a muted, tentative light over the sweep of lawn, dulling the green grass and darkening the bank of forest at the edge of Julie’s property. Without agreeing on a direction we walked around the side of the barn-house to the front, where a bright seam of orange marigolds defied the shadowy imminence of rain. Spring, glorious spring, and my heart was aching. I knew I was going to send Bobby home alone.

In the daylight I could see how isolated Julie’s house was; none of her neighbors was visible from herproperty. The barn sat looming on a plot of landscaped green that extended back from the intersection of two roads, gray ribbons of asphalt that crossed each other at an uneven angle, with one becoming a hill and the other curving into a turn. We were alone here (except

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher