![Here She Lies]()

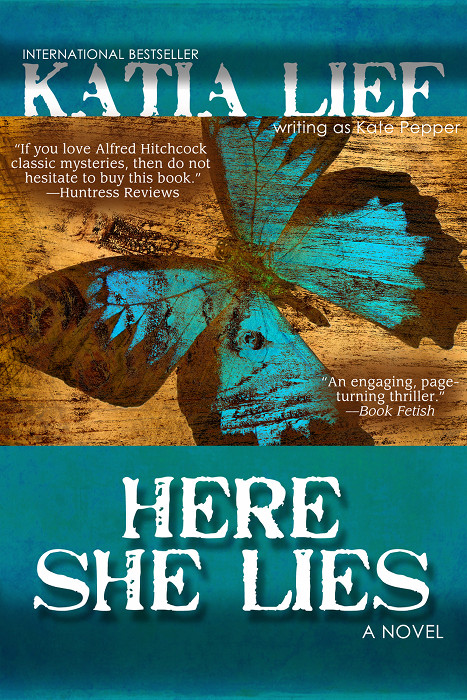

Here She Lies

blow that left the imprint of a letter. A had a broken leg. P, a broken face. U always struck with a shadow. Dad would carefully correct his stories with a black pen and a bottle of Wite-Out. I hadn’t thought about that typewriter for many years and remembered now that Julie and I had let the liquidator sell it when the house was emptied in preparation for sale. We had walked out of that house one day, not really knowing we would never return. We had moved from there to here on a wave of time, and now another wave had overtaken us and I was hovering on the crest, waiting to see where it would plunk me down.

Here in jail the nature of waiting was completely different from last week’s wait at the inn. This wait was bottomless. Endless. It was amazing how fat and long and droopy individual minutes could become. You sank into them, grew paralyzed in your state of waiting. Sitting on your thin mattress. Or standing, feeling the cold floor soak through your thin plastic sandals. Everything had been confiscated from me,even the flow of time; I had no watch, there were no clocks on the walls and the guards thought it was fun to keep us in temporal darkness. All I had was the sun sliding up and slipping down my window strip. I stopped counting hours after lights-out. It didn’t matter anyway: time. Thinking of time. Speaking of time. I couldn’t.

I didn’t eat anything, either, because the food was so bad. Now I understood something the prisoners back home used to joke about, how you knew how good prison food was once you spent a few nights in jail waiting for your trial. Jail food was awful — I hadn’t known meat could be that tough or how nimbly human hair stuck to undercooked potato. Twenty-four hours on the inside and I could feel I’d gotten thinner, making my recent efforts to diet really absurd. Even my breast milk went on strike, to the point that I didn’t even bother requesting a pump.

No sister, no baby, no milk, no body, no time, no me.

Bobby visited after lunch the second day, and mercifully he brought Lexy. He had to know how much that meant to me. I admit I had worried that he would keep her away from the correctional facility in case floating errors might randomly insert themselves into her psyche and mysteriously screw her up for life. (As if being wrenched away from her mother, now twice, would not leave a scar.) So when he showed up with her, I felt renewed confidence that he had my best interests at heart.

We were given a private visiting room. I don’t know why (though I could guess why, since the room was in a cell that locked up tight: it must have been for violentoffenders, you know, really scary people like me). Four stools were affixed to the base of a round stainless-steel table and the room was brightly lit. A boxy in-house phone hung off one cinder-block wall.

As soon as the guard locked us in and turned her back, I took Lexy into my arms. I didn’t offer my breast and she didn’t try to nurse; it seemed wisest to let her adjust exclusively to the bottle since I had no idea when I’d be out of here. She had grown more restless than even yesterday and could not be contained in my arms for long, so I put her down and watched her crawl around, grateful that Bobby had dressed her in long pants so her knees wouldn’t get chewed up by the concrete floor.

Bobby had thoughtfully brought a few family pictures for me to keep in my cell (I was allowed up to ten): shots of the three of us taken by Julie and a couple of him and Lexy taken by me. He set the pile on the table. Looking through the photos, I saw he had also brought one of Lexy and me, but on closer inspection I saw that it wasn’t me — it was Julie. Weeping, I ripped it in half, fourths, eighths.

“I’m sorry,” Bobby said. “It was a stupid mistake.”

“Can’t you tell us apart?”

“Yes, I can.” He leaned from his neighboring stool to hold me and I could smell him: spicy, warm, familiar. “You’re depressed, sweetie,” he said, stating the obvious, but I forgave him.

“Don’t I deserve to be? Julie’s destroyed me, Bobby. She’s really done it.”

“You won’t be in here much longer.”

“But neither of us ever thought it would go this far,” I said, “so what does it matter what we think?”

“Elias is working really hard.”

“Yeah, right.”

“He is, Annie, but these things take time.”

“Do you remember that guy at the prison — Ernesto, the lifer? He always said he was

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher