![Hexed]()

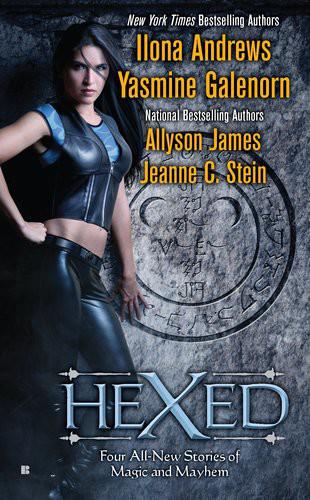

Hexed

on your shoulder the size of a two-by-four. You think that because it takes you two minutes to come to when you shift and because you’re not the best fighter we’ve got, you have something to prove. And you do this by making metal cages with four wheels go really fast without any point. You don’t win anything, you don’t accomplish anything, and you hurt yourself all the time. You’re right—that will show everyone how hard-core you are.”

“Aargh!”

“The only thing you’re proving is that the smartest woman I know has zero common sense. You have powerful magic, you’re smart, you’re competent, but none of that matters. I have a dozen Nadenes, I only have one you. What good would Nadene do me right now? And I know you’re female. I’ve noticed. This hysterical thing you’re doing right now, that’s female. If you were a man, I would’ve put your ass to haul rocks for the Keep a long time ago.”

I heaved up the bucket.

“Don’t do it,” he warned.

I hurled it at him, water and all. Water splashed, and then a completely drenched, pissed-off Jim grabbed the bucket, scooped water from the pond, and tossed it at me. Water hit me in a cold rush.

I turned around and stomped off.

“Where are you going?” he called.

“Away from you!” I sat on the bench at the far end of the pond.

“You’re supposed to keep me awake.”

“I can keep you awake from here. If I see you falling asleep, I’ll curse you with something really painful.”

“You do that. You’re still wrong.”

“Whatever.”

THE MORNING CAME way too slow. Jim had almost dozed off four times and I ended up moving next to him, with my bucket. At some point he asked me if my girly emotional outbursts were over, and I swore at him for a while in Indonesian. And then he ruined it by asking me what some of the words meant, and of course I had to teach him how to pronounce them properly.

It’s good that my mother stayed inside, or I would have gotten another lecture on how to behave as a proper daughter.

It was seven o’clock now and we were standing on Pryor Street, in front of a grimy white arch marking the entrance to Kenny’s Alley. Set apart from the main Underground, Kenny’s Alley had no roof, and entering through the narrow ramp off of Pryor Street was the quickest way to get there. It was also the most dangerous—to get down, I’d have to walk up the narrow ramp that squeezed between two brick buildings, enter the old train depot, and then walk along the balcony and down two floors, all filled with people who’d kill me for a dollar. Sometimes people who entered the Underground through Pryor Street didn’t come out.

The wind swirled, rushing down the narrow gap between the buildings, and flung the Underground’s scents into my face: odors of a dozen of animal species mixed with the bitter stink of stale urine, human and otherwise, old manure, fish from a giant fishmonger tank, pungent incense, and salty blood. The revolting amalgam washed over me and I had to fight not to retch.

At least the magic had vanished during the night. Usually the miasma rising from the Underground made my head hurt.

“You don’t have to do this,” Jim said.

“Yes, I do.”

He reached over and put his arm around me. I froze. There was so much strength in that muscular arm that suddenly I felt safe. The scent of him, the comforting, strong Jim scent, touched me, blocking out other smells. I would know that scent anywhere. Here he was hugging me. I had wished for it and now I just wanted to cry, because no matter what I did, no matter how much I raced or how belligerent I got, he would never want me. Not in that way.

I stepped away from him, before I lost it. “I’m going inside. If I go inside a shop, give me about five minutes. If I don’t come out . . .”

“I’ll come in,” he promised.

“Don’t fall asleep.”

“I won’t.”

I looked into his brown eyes and believed him.

“Okay,” I murmured. “I’m going now.”

I turned and headed down the narrow alley, into the dark belly of the Underground. Panhandlers and street people lined the ramp and the balcony, swaddled in filthy clothes, hats and tins in front of them. This early in the morning they didn’t even bother begging. They just stared at me as I passed by, all except an old black man, who was doing a wobbly moonwalk across a covered walkway, gyrating to the beat of some melody only he could hear. His eyes were wide-open; he looked

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher