![High Price]()

High Price

the provocatively headlined article had used it to support a claim that cocaine-related deaths and other problems had been described early in the drug’s history. I wanted to see for myself what arguments it made. Though immediately offended by the language of the header, I was also excited because I’d never seen this paper cited before. If I could track it down, I might be able to find a very early description of cocaine to add to my work, which might impress my professors.

My first surprise came when I read the full reference: the “journal” in which the article had been published did not seem to be some august peer-reviewed medical publication. It was, instead, listed oddly as “New York,” perhaps having been cut off by mistake. I can’t recall how, but I eventually ascertained that what was meant was actually the New York Times , and, even though I now knew it was just a newspaper story published on February 8, 1914, 1 I decided to get a copy of the whole article.

I walked across the snowy campus to Coe Library, the university’s main reference library. Old newspapers were stored there on clunky microfilm, not kept in the more specialized science library where I did most of my literature searches. I looked up the citation in a big bound index with a thick, worn cover. Then I requested the relevant reels of microfilm and watched them scroll blurrily across the reader’s screen until I found the right frames. That was what research was like in the days before the Internet.

The first thing I could read besides the headline was the subhead: “Murder and Insanity Increasing Among Lower Class Blacks Because They Have Taken to ‘Sniffing’ Since Deprived of Whisky by Prohibition.”

I was surprised at how shocked I was to see that. I knew intellectually that such blatantly racist writings existed and that it was once acceptable to print such things in respectable papers, but it had always seemed abstract and distant to me. It was very different to see the words in black-and-white on the pages of the New York Times , the publication that to this day is seen as the “paper of record.” It was as different as reading about slavery in a history book is from holding in your hand an iron shackle once used to bind a real human being. Or as different as learning about the Holocaust in history books, versus actually going to Auschwitz and seeing firsthand the shoes of the children killed there.

But what shook me even further was how similar the article was to modern coverage of crack cocaine in the mid-1980s. The author, who was a medical doctor, wrote:

Most of the negroes are poor, illiterate and shiftless. . . . Once the negro has formed the habit he is irreclaimable. The only method to keep him away from taking the drug is by imprisoning him. And this is merely palliative treatment, for he returns inevitably to the drug habit when released. 2

This rhetoric was unsettlingly modern. For example, recall what Dr. Frank Gawin told Newsweek on June 16, 1986: “The best way to reduce demand would be to have God redesign the human brain to change the way cocaine reacts with certain neurons.” The message is that crack users are irretrievable, except for divine intervention. Of course, in 1986 explicit reference to race in such a context was no longer acceptable; instead, crack-cocaine-related problems were described as being most prevalent “in the inner city” and “the ghettos.” The terms inner city and ghetto are now code words referring to black people.

Dr. Edward H. Williams, author of the “Fiends” article, went on to claim:

[Cocaine] produces several other conditions that make the “fiend” a peculiarly dangerous criminal. One of these conditions is a temporary immunity to shock—a resistance to the “knock down,” effects of fatal wounds. Bullets fired into vital parts that would drop a sane man in his tracks, fail to check the “fiend.” 3

In other words, cocaine makes black men both murderous and, at least temporarily, impervious to bullets. By the way, the author was describing the effects of cocaine taken by snorting it. Attempting to further bolster his case, the writer then added anecdotes from southern sheriffs, who claimed to need higher-caliber bullets to take down these black “fiends.” He also contended that cocaine improves the marksmanship of blacks, making us even more dangerous to the police and society.

I began to wonder how many of the “truths” that I now

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher

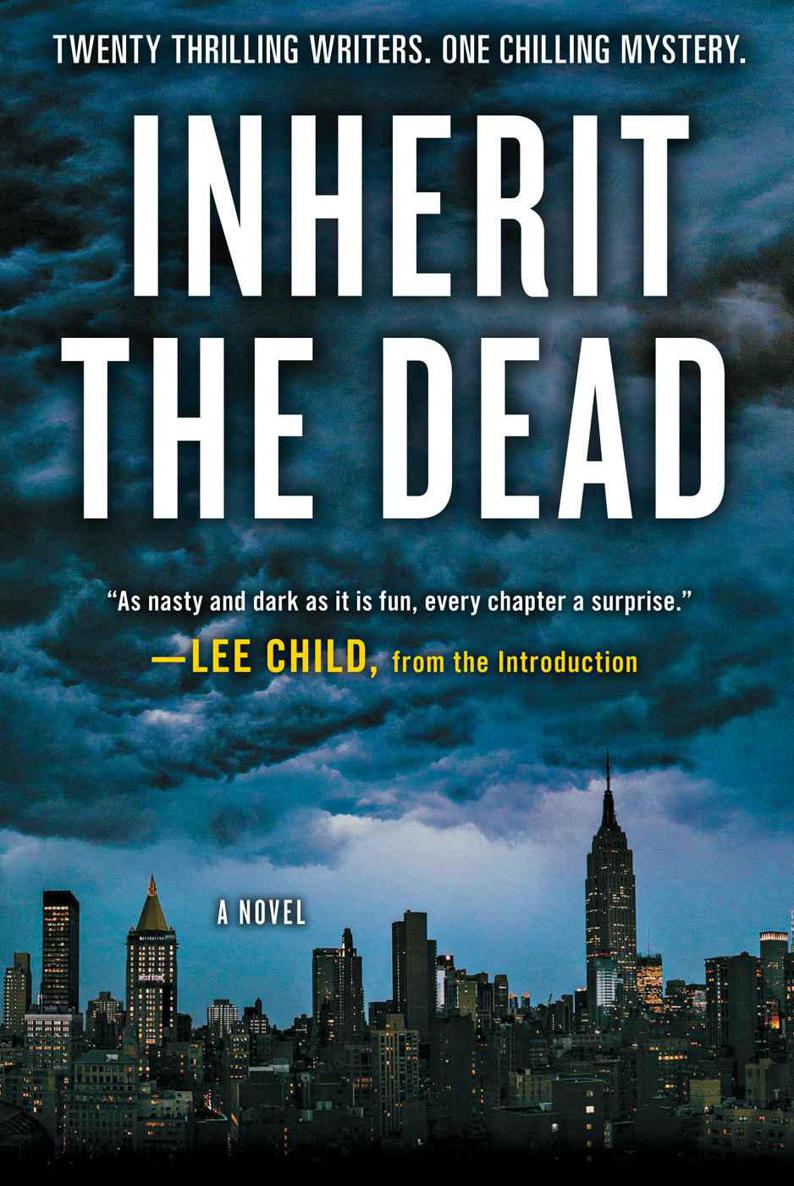

![Inherit the Dead]()

Inherit the Dead Online Lesen

von

Jonathan Santlofer

,

Stephen L. Carter

,

Marcia Clark

,

Heather Graham

,

Charlaine Harris

,

Sarah Weinman

,

Alafair Burke

,

John Connolly

,

James Grady

,

Bryan Gruley

,

Val McDermid

,

S. J. Rozan

,

Dana Stabenow

,

Lisa Unger

,

Lee Child

,

Ken Bruen

,

C. J. Box

,

Max Allan Collins

,

Mark Billingham

,

Lawrence Block