![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

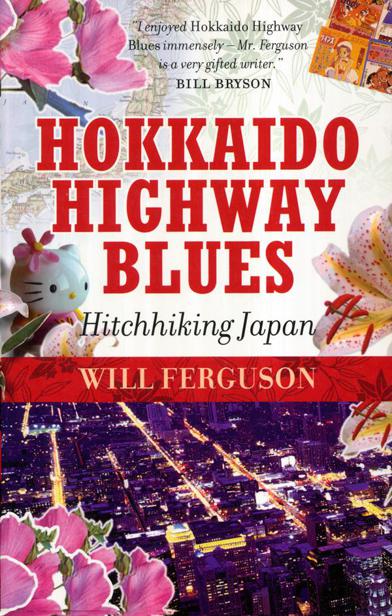

Hokkaido Highway Blues

gaijin-san,“ he insisted, “is a term of affection.” Sure enough, once I started paying closer attention to who was saying gaijin and who was saying gaijin-san, I discovered that Mr. Araki was right. Gaijin is a label. Gaijin-san is a role.

In Japan, people are often referred to not by their name but by the role they play. Mr. Policeman. Mr. Post Office. Mr. Shop Owner. As a foreigner, you in turn play your role as the Resident Gaijin, like the Town Drunk or the Village Idiot. You learn to accept your position, and even take it as an affirmation that you do fit in—albeit in a very unsettled way—and you begin to enjoy Japan much more.

13

MS. MAYUMI TAMURA and Ms. Akemi Fujisaki were on their way into the city to see a concert by a Japanese rock band called Blue Hearts. Mayumi and Akemi were young, high-spirited women, and together we managed to wedge my pack and my oversize self into the backseat of their Incredible Shrinking Car (it seemed to grow smaller and smaller as we drove). My knees were resting under my jaw. Akemi turned around to talk with me as Mayumi pulled out onto the highway and pointed us toward Miyazaki City.

Initially they wanted to talk about Japanese pop music, but my knowledge was limited to a handful of names. I asked them if Blue Hearts was a popular band. No, not really. Did they like Blue Hearts? No, not really. Then, laughing at my puzzled look, they explained that there was so little to do down here in this southern corner of Japan, so few distractions, that they take what they can get.

I asked them if they were good friends, and their eyes met, almost slyly, and a smile passed between them. “Best friends.” Akemi reached over, lightly, and touched Mayumi’s hand.

Great. I’d caught a ride with Thelma and Louise. Which was fine, as long as they didn’t go driving off a cliff.

Mayumi, the driver, could speak English. She studied it with a determined passion, fitting her studies in during afternoons and work breaks and free evenings. She was a maid at an inn near Cape Toi. She was single, female, and gainfully employed—which in Japan translates as “world traveler.” One of the acute ironies of the Japanese corporate-male philosophy is that the men of Japan do not have much time to enjoy themselves on extended holidays. Young women, on the other hand, may be underpaid and underappreciated, but in many ways they have more freedom. Their work is rarely their life, and it is they who are Japan’s new breed of traveler. The men of Japan are lousy travelers and even worse expatriates. The women, in contrast, are more aware of the world: less xenophobic, more adventurous.

This newfound worldliness of Japanese women has also been partly responsible for a phenomenon known as “the Narita divorce.” It begins during the honeymoon, when the young husband discovers—to his eternal chagrin—that his new wife is more sophisticated, more self-assured, and more at ease in a foreign country than he is. He also discovers that his samurai prerogatives are meaningless once he leaves the maternal bosom of Japan. The young wife, in turn, notices how un worldly, how bumbling, how inept her husband is, and by the time they get back to Narita International Airport in Tokyo, they can’t stand the sight of each other. Fortunately, in Japan the marriage certificate is not usually signed until long after the ceremony, often not until the honeymoon is over. This acts like an escape clause. A couple returning from their disastrous first trip abroad can part ways at Narita, never to see each other again, and the marriage is effectively annulled.

Mayumi had traveled through Canada and Europe, and she was now planning a trip to London—and this time she was taking Akemi. The relationship between Mayumi and Akemi was, to a certain extant, one of senpai to kōhai , senior to junior, teacher to student. In Japan, absolute equality between two people is very rare. One person is always older or better-trained or more knowledgeable. This is true everywhere in the world, but nowhere is it quite so entrenched as in Japan, where the senpai/kōhai system is the basis of virtually every relationship. It is not always apparent, but the more attuned you become to the nuances of relationships in Japan, the more often you see it. The senpai/kōhai system is not meant to be an antagonistic master/serf relationship, though it does degenerate into this at times. More properly, it is the sense of a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher