![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

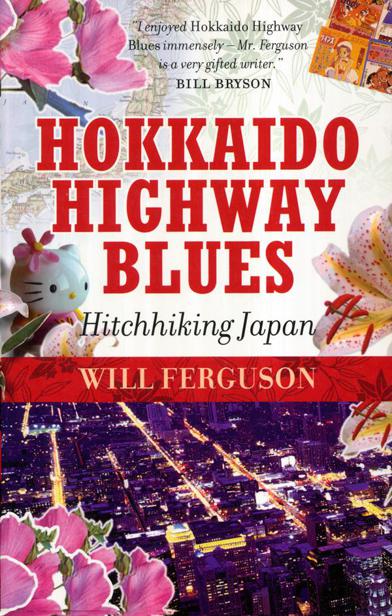

Hokkaido Highway Blues

It is an island culture, but it also has the patience (and the suspicions) of a farmer: a fascination with seasons, with long-term plans, with harvests. The sea binds them. The fields define them. The cities of Japan are travesties precisely because Japan is still—at heart—an agricultural country. This is changing of course. The cities are becoming cleaner, greener, more comfortable, and the villages are dying—but it is a slow death, and not an inevitable one. It is de rigueur among the overly romantic to wail and bemoan the death of the Japanese village, but Japan is simply finding a new equilibrium. The elegies are premature; there is strength in reserve.

The farmers were having trouble getting on the boats as the sea rocked and tilted them. The motors began with great bronchial coughs, and the fishermen’s sons backed their beasts away from the pier. “There are about ninety monkeys on the island,” I heard the fishermen begin, shouting over the motors. “They are called the Wisest Monkeys in Japan.” And then, before anyone could ask: “They wash their potatoes before they eat them.”

12

“GOOD-BYE, GAIJIN-SAN.” That was the farewell I received from a lady as I passed through Nango Town. “Good-bye and thank you.”

There was a time I would have rankled over someone calling me gaijin-san. The word gaijin means “outsider,” and is derived from the term gai - koku-jin, “outside-country-person.” When the suffix — san is added to gaijin, it means Mr. Outsider. This was how the lady in Nango referred to me. Most Japanese insist that the word gaijin is strictly an abbreviated form with no undertone of racism intended, but they are wrong. Like gringo, the word gaijin has an edge to it. And when I ask my Japanese friends how they would feel if I were to refer to them in a similarly abbreviated form —Jap —their jaws harden and they insist that it is not the same thing.

Like most visible minorities living in Japan, I went through a hypersensitive phase. It happens after the initial euphoria has worn off and you realize, “Hey! Everyone is talking about me! And they’re looking at me. What do they think I am, some kind of foreigner or something!”

We become Gaijin Detectors. It’s like a silent dog whistle. It got so I could detect a whispered, “Look, a gaijin!” across a crowded street, and spin and glare simultaneously at everyone within a fifty-mile radius.

Even when I could understand the language, I ran into problems. The word for the inner altar of a Shinto shrine sounds exactly like gaijin. I remember visiting a shrine in Kyoto and having a tour group come up behind me. The tour guide pointed in my direction and said, “In front of us, you can see the inner altar. This inner altar is very rare, please be quiet and show respect. No photographs. Flashbulbs can damage the inner altar.“ Except, of course, I didn’t hear inner altar, I heard foreigner. It was a very surreal moment.

Looking back, the biggest culture shock about Japan was not the chopsticks or the raw octopus, it was the shock of discovering that no matter where you go you instantly become the topic of conversation. At first it’s an ego boost. You feel like a celebrity. “Sorry, no autographs today, I’m in a hurry.” But you soon realize that in Japan foreigners are not so much celebrities as they are objects of curiosity and entertainment. It is a stressful situation, and it has broken better men than me.

And yet it seems so petty when you put it down on paper: They look at you, they laugh when you pass by, they say “Hello!” They say “Foreigner!” They even say, “Hello, Foreigner!” But it’s like the Chinese water torture. It slowly wears you down, and this relentless interest has driven many a foreigner from Japan.

It is still fairly mild. I tried to imagine what would happen if the tables were turned. I think of my own hillbilly hometown in northern Canada, and I wonder what kind of greeting the beetle-browed, evolutionarily challenged layabouts at the local tavern would give a lone Japanese backpacker who wandered into their midst.

I still hate the word gaijin and I still hate it when people gawk at me or kids follow, shouting, “Look, a gaijin! A gaijin!” But I have also learned an important distinction, and one that has made a huge difference to my sanity. It was explained to me by Mr. Araki, a high-school teacher I once worked with. “Gaijin means outsider. But

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher