![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

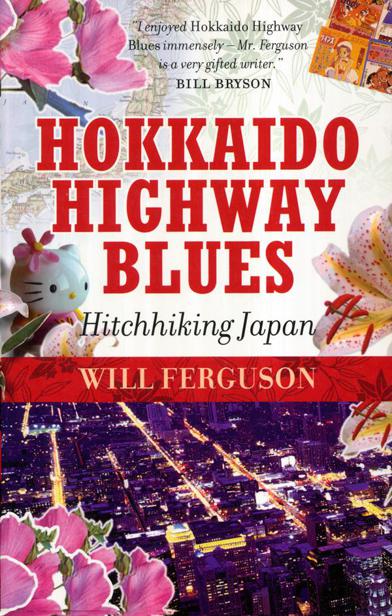

Hokkaido Highway Blues

chain of knowledge being transmitted from one to another. In the case of martial arts or company training, the position is explicit, but even among friends there is usually an unstated understanding of who is to be the senpai and who is to be the kōhai. (And every kōhai naturally aspires to becoming a senpai one day.) Everyone in Japan is entangled—or nurtured, depending on your bias—in an interconnecting web of uneven relationships, here the senpai, here the kōhai.

In Mayumi and Akemi’s case, their friendship easily divided into senpai (Mayumi) and kōhai (Akemi). Mayumi was the same age as Akemi, but she had traveled more, done more, seen more. It wasn’t a matter of Mayumi dominating Akemi, it was simply a rapport that they—like most Japanese—felt comfortable slipping into. Just as Americans feel most at ease with unpretentious jocularity.

Mayumi and Akemi were a society of two. They had a secret map that would take them away. They told me far more about themselves than they really ought to (and more than I feel comfortable divulging). When you are a hitchhiker, people spill their lives into your lap. Things they would never tell their family, they gladly surrender to a hitchhiker precisely because the hitchhiker is a stranger, a fleeting guest, a temporary confidant. But there is also something about the physical position; there is little eye contact. Drivers watch the road and you talk with parallel vision, without the extended face-to-face of normal conversations. It is almost like talking to someone at night in bed, when the voices are disembodied and anything seems possible.

A sea change is under way, and Japanese women are the ninja saboteurs. In Japan it is not a revolution, but sedition. It is not about confrontation, but subterfuge. Together, Mayumi and Akemi were charting a course. A trip to Britain and then a journey through Europe, a change of jobs, whispers of work abroad. Secret passages. Hidden dens. Escape.

Mayumi was unfolding the world for Akemi, like a glass gift in layers of silk. I imagine that courtesans once opened the world for their younger novices in much the same way. It is a sensual discovery to find yourself stepping from an isolated island into a global bazaar of experiences and possibilities. Akemi had that impatient panic of people on the verge of something new. It is like a first kiss, this journey abroad, and she twisted in her seat, almost breathless, and asked me about the world.

She wanted my advice about British society. Not being British, I gave it. (It is one of those wonderful perks about being a foreigner in Japan that you are accepted as an expert on everything from Australian koalas to American gun laws.)

“Is Britain really so foggy?”

“Yes, very foggy,” said I, suddenly an expert on fog and all things mist-related.

“But how can people breathe if it is so foggy?”

“Well, they’re British, you see. Used to it.”

“Is Britain safe?”

Mayumi answered this one, speaking in near exasperation. “Of course it’s safe, I told you that many times. The world is not as dangerous as Japanese think.”

But Akemi wanted to hear it from me. “Is it really safe?”

“Well,” said I, “it is safe. Not as safe as Canada, of course, but still fairly safe, in a foggy British sort of way.” And on I went, building up steam, flinging out cultural stereotypes and pontificating about national traits, with Akemi all but taking notes as I went. When we exhausted Britain we moved on to France and then Switzerland—a country that I have not technically visited. Not that this stopped me.

“The Swiss are a very tidy people,” I assured them.

By one of those odd quirks of life, it turned out that Mayumi and I had a mutual acquaintance: Paul Berger. Paul is a wry, perpetually perplexed New York exile who wrote his own book on Japan, The Kumamoto Diary.

“I met Paul in the Rock Balloon,” said Mayumi. “Do you know the Rock Balloon? It’s in Kumamoto City.”

Do I know the Rock Balloon? The Rock Balloon is a “gaijin bar,” where debauched foreign reprobates drink cheap beer and dance themselves into hormonic frenzies as they pursue equally debauched Japanese. Of course I know the Rock Balloon.

I tried to get some dirt on Paul—maybe he had tried to cruise Mayumi with a line about being Paul Simon’s shorter brother, or maybe she poured her drink on his head and slapped his face or something—but no, Paul had been a perfect

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher