![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

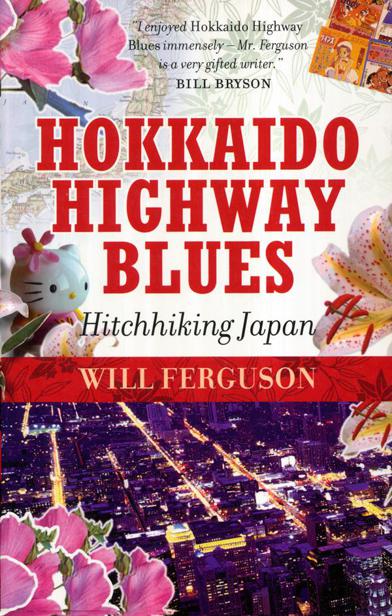

Hokkaido Highway Blues

emotion, alternating between attraction and repulsion, affection and anger—back and forth. But the image is false. These feelings do not alternate. They are inseparable. As inseparable as the scent of urine and incense on the same wind. The same festival that beguiles you, also excludes you. One does not love and then hate and then love Japan like a metronome. One lovehates it, one wants to draw nearfar to it, to gostay.

For most Westerners, one urge or the other eventually wins, and instead of inseparable feelings you have only to go or to stay. But there are some who are caught in the middle, suspended by opposing desires. They are lost and not sure if they want to be found. They try to run in two directions at once and fail. Like a deer on a highway.

Such were the morose thoughts that pursued me through the drizzle and oily refractions of Uwajima. Just be glad you weren’t keeping me company that night; I was as deep as I ever want to go. Everything was fraught with significance, every gesture portentous, every glance an omen.

I sought refuge from myself in a crowded bar and grill, and from the moment I stepped inside, I was everybody’s best friend in the world. “Welcome! Welcome! Come in!“ This was in the time-honored tradition of Japanese blue-collar eateries: to be as noisy and as nonphilosophical as humanly possible. Everything is everyone else’s business and you never whisper when you can shout. “Ah, Mr. Foreigner! Welcome, Mr. Foreigner!”

The Japanese call these places aka-chōchin, “red lanterns,” what we in the West might call greasy spoons. But in red lanterns it is not just the spoons that are greasy. The chopsticks, the menus, the tabletops, the plates, the walls, the cooks permanently and the customers eventually, everything gets covered in a thin film of grease, what might otherwise be called “atmosphere.”

No tea-ceremony subtleties here. It was in-your-face hospitality, back-slapping, boisterous, and very loud. I had learned to be wary of such welcomes. Westerners are often treated as sources of amusement and ridicule in Japan, and it can be difficult to spot the difference between derision and friendly chiding. The line is fine, almost invisible, between someone mocking you and someone genuinely curious. Tonight, thankfully, there was no mockery in the air. I sat down at the counter across from a choreography of cooks performing circus feats with knives and whisks, their hands a blur, dicing cabbage, stirring woks, and tossing up plate after plate of Japanese shishkabob.

One of the cooks, a haggard young man with a week’s worth of stubble, leaned over the counter and screamed, “What do you want!” I was two feet away. I gave him a preliminary list and he announced to the room, “He speaks Japanese! The foreigner speaks Japanese!” but no one was much impressed save the cook himself. The owner came over and chased him away.

The shop was named Sasebo, after a city in the owner’s home prefecture of Nagasaki. The Amakusa Islands where I used to work had once been a part of Nagasaki, and even now there is a sentimental bond between the people of the islands and those of the peninsula. When I told the owner that I had lived in Amakusa it was as though I had declared myself to be his long-lost brother come home with a winning lottery ticket in my pocket. “Beer!” yelled the Master of Sasebo like a wounded soldier calling for a medic. “Beer!“

The Master of Sasebo was a man of immense girth and good humor. The Uwajima City High School baseball team, which his shop helped sponsor, had gone to the national championships in Osaka and been thoroughly trounced. He gave me a souvenir baseball cap. His previous restaurant had burned to the ground last spring. He gave me a souvenir lantern from the place. I half expected him to present me with photographs of some distant dead relatives as well, but he didn’t.

Instead, he ordered a plateful of deep-fried battered squid, which looked just like onion rings but tasted just like deep-fried battered squid. I hate accepting food at restaurants in Japan, because the people doing the proffering inevitably pick the least appetizing item on the menu. No one ever sends me pizza or french fries, it’s always squid this and squid that. Later, for a change of pace, the Master ordered a dish of raw octopus and then, perhaps to make amends, he presented me with a plate of artfully arranged strawberries— which don’t really go

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher