![Hokkaido Highway Blues]()

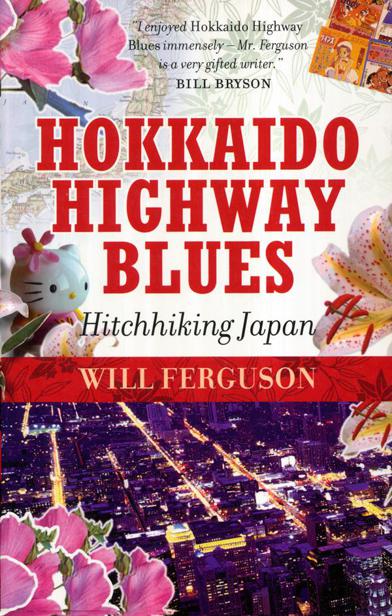

Hokkaido Highway Blues

outsider; to have bumped into other Westerners would have reduced me in my pride to the level of tourist. I tell myself often that I am not a tourist. I exist somewhere else, in between voyeur and exile. Which is to say, my journey is almost complete. In Japan, the movement from Tourist to Exile to Insider is one that ends at Exile. There is no final step inside. We are kept at arm’s length by the arc of a bow, by the sound of a drum.

The Japanese are not a coldhearted people. Sometimes I wish they were, it would make leaving easier. The problem is not that you aren’t welcome. You are. You are welcome as an outsider. The problem is not exclusion, the problem is partial exclusion. The door is open but the chain is on. One hand beckons and the other blocks. Like a hostess in a snackbar, Japan flirts its way into our hearts, it pours our drinks, it strokes our ego, it smiles and sighs and listens to our stories, and then in a moment of silence it asks: “How did you ever get so fat?” Japan is not the Land of the Broken-Hearted, it is the Land of the Wounded Pride. It is not that I want inside and can’t that bothers me. I do not want to be Japanese. What rankles my Western heart is that it doesn‘t matter what I do or do not want. I could not be Japanese, anyway, even if I wanted to be, and this is so hard on the pride. We want to reject, but we do not want to be rejected.

For expatriates in Japan, the question is this: Do you really want to go all the way inside or are you just hurt that nobody asked you to?

Strangely enough, the closest I ever came to feeling I belonged to Japan-one does not belong in Japan, one belongs to Japan—was during a festival, when I labored with an army of men from my neighborhood to carry a shoulder-aching moveable shrine, the size of a small house, in the city’s summer festival. We were dressed in blazing red jackets and straw sandals. To gird ourselves for strength and stamina we wrapped mummy-cloths of white linen around our midriffs and twisted banzai headbands around our brows. The shrine was both our glory and our burden, like being born Japanese I suppose. A Shinto priest blessed it with a sweep of paper. We then hoisted it onto our shoulders and entered a traffic jam of other such shrines. We elbowed our way into the throng. We chanted challenges. We swerved and collided. We battled our way down main street and, as we went, people threw buckets of water at us and sprayed our heads with beer. We were running a gauntlet and at the end of it we collapsed, soaked in sweat and water and alcohol. We were triumphant. We ranted and raved. We congratulated ourselves hoarse and far beyond the level of actual achievement. Damn, it was fun. Then one of the men turned to me and said, “You foreigners are so much stronger than we Japanese,” and instantly I was outside the circle again, looking in. Waiting. In exile.

6

THE UWAJIMA FESTIVAL did not degenerate into water balloons and beer baths. It was restrained to the point of sadness, and the only water that touched me was a faint mist that came down near the end. It shrouded the castle in soft-focus and reduced the crowds to outlines. Then the footlights came on and the castle glowed as though lit from within, like a paper lantern in the night.

Down below, in the town of tradesmen and alehouses, the neon was flickering on. The streets were slick with rain. Crowds of revelers spilled out, some still in costume, some already steeped in saké and song. A man yelled “Hey, foreigner!” and came over to present me with a can of beer. “For you, Mr. Foreigner. Japanese beer. Number one! Japan is an international country!” and he returned amid hoots and laughter to his circle of friends.

I dropped the can, unopened, into the first garbage bin I came upon.

There was an incident of aromas. I entered a side street lined with restaurants and noodle shops, and I was surrounded by smells. Ginger wrapped in soy wrapped in smoke. At the same time, under the shelter of a small roadside altar, incense sticks were burning, and even in the mist and haze you could smell it, the scent of spice and prayers. That, and the odor of urine from an alley and untreated sewage running under concrete slabs along the gutter. The smells met and mingled.

They call it the Seidensticker Complex, after the American scholar and translator, and it describes the ambivalent feelings that torment long-term foreign residents in Japan, a pendulum of

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher