![Kushiel's Dart]()

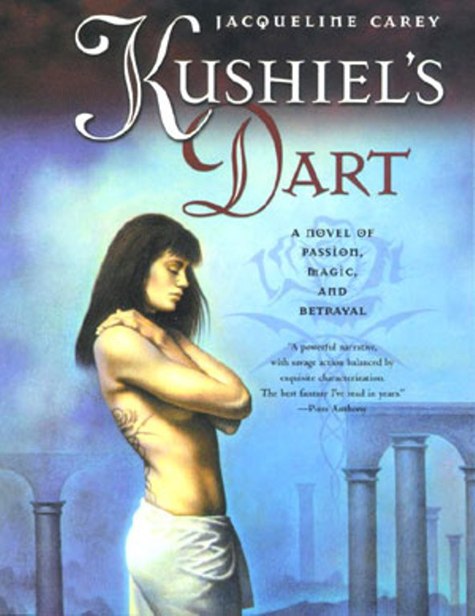

Kushiel's Dart

lineage-but an excessively wealthy one, by virtue of an exclusive charter with the Stregazza family in La Serenissima.

His gaze followed Alcuin and his face was sick with desire.

When the last rays of sun had gone and darkness filled the long windows around the balcony, Cecilie clapped her hands and summoned us to dine. No fewer than twenty-seven guests were arrayed about the long table, ushered to our seats by solicitous servants clad in spotless white attire. Dishes came in an unceasing stream, soups and terrines followed by pigeon en daube, a rack of lamb, sallets and greens and a dish of white turnips whipped to a froth which everyone pronounced a delight of rustic sophistication, and all the while rivers of wine poured from chilled jugs into glasses only half-empty.

"A toast!" Cecilie cried, when the last dish-a dessert of winter apples baked in muscat wine and spiced with cloves-had been cleared. She lifted her glass and waited for silence. She had the gift, still, of commanding attention; the table fell quiet. "To the safety of our borders," she said, letting the words fall in a soft voice. "To the safety and well-being of blessed Terre d'Ange."

A murmurous accord sounded the length of the table; this was one point on which each of us agreed. I drank with a willing heart, and saw no one who did not do the same.

"Thelesis," Cecilie said in the same soft voice.

Near the head of the table, a woman rose.

She was small and dark and not, I thought, a great beauty. Her features were unremarkable, and her best asset, luminous dark eyes, were offset by a low brow.

And then she spoke.

There are many kinds of beauty. We are D'Angeline.

"Beneath the golden balm," she said aloud, simply, and her voice filled every corner of the room, imbued with golden light. "Settling on the fields/Evening steals in calm/And farmers count their yields." So simple, her lyric; and yet I saw it, saw it all. She offered the words up unadorned, plain and lovely. "The bee is in the lavender/The honey fills the comb," and then her voice changed to something still and lonely. "But here a rain falls never-ending/And I am far from home."

Everyone knows the words to The Exile's Lament . It was written by Thelesis de Mornay when she was twenty-three years old and living in exile on the rain-swept coast of Alba. I myself had heard it a dozen times over, and recited it at more than one tutor's behest. Still, hearing it now, tears filled my eyes. We were D'Angeline, bred and bound to this land which Blessed Elua loved so well he shed his blood for it.

In the silence that followed, Thelesis de Mornay took her seat. Cecilie kept her glass raised.

"My lords and ladies," she said in her gentle voice, marked by the cadences of Cereus House. "Let it never be forgotten what we are." With a solemn air, she lifted her glass and tipped it, spilling a libation. "Elua have mercy on us." Her solemnity caught us all, and many followed suit. I did, and saw Delaunay and Alcuin did as well. Then Cecilie looked up again, a mischievous light in her eyes. "And now," she declared, "Let the games begin! Kottabos!"

Amid shouts of laughter, we retired to the parlour, united by love of our country and Cecilie's conviviality. Her servants had prudently removed the carpet, and in its place was a silver floorstand. Standing on tripodal legs, it pierced and held a broad silver crater, polished to mirror-brightness. Chased figures around the rim depicted a D'Angeline drinking party, a la Hellene. D'Angelines regard the Golden Era of Hellas as the last great civilization before the coming of Elua, which is why such things never go out of style.

Spiring out of the center of the crater, the stand rose to some four feet and terminated. Balanced atop its finial was the silver disk of the plastinx . Cecilie's servants circulated with wine-jugs and fresh cups; shallow silver wine-bowls with ornate handles.

To get to the lees, of course, one must drink what is poured, and although I had been prudent in my drinking, I felt it warm my blood as I emptied my cup. It is an art which must be practiced, twirling the handle about one's ringer, flinging the last drops of wine in such a way that they strike the plastinx , knocking it into the crater so that it sounds like a cymbal.

When I took my turn, five or six others had gone before me, and while some had hit the plastinx , none had knocked it off the shaft. I did not even do so well as that, but Thelesis de Mornay smiled kindly

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher