![Kushiel's Mercy]()

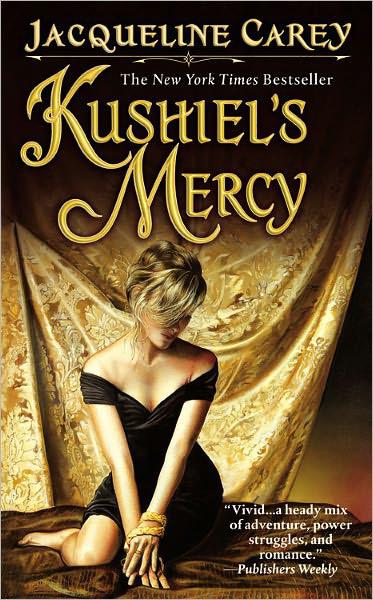

Kushiel's Mercy

incandescent. It never failed to shock and thrill me, how utterly and thoroughly my cool, collected cousin was willing to surrender to complete abandonment. We hadn’t even begun to test the limits of it. I watched her ride me to climax, again and again, waiting a long time to join her.

“Mmm.” Sidonie collapsed on my chest. “Also a good talk.”

I ran a few strands of her hair through my fingers, watching her blurred, black gaze sharpen, coming back from wherever pleasure took her. “Do you suppose it will always be like this between us?”

Her lips curved. “Always?”

I nodded. “Always and always.”

Sidonie kissed me. “Gods, I hope so.”

Five

The months that followed were among the best of my life.

They weren’t perfect; Elua knows, nothing ever is. Not in my life, anyway. But this came close.

I’d won the respite I’d prayed for. The Queen had made her pronouncement; the gauntlet had been cast. I had countered. My letter to Hyacinthe was dispatched by courier; the Master of the Straits made a prompt reply. There was a debt of honor between us, he wrote. I had played a crucial part in Phèdre’s quest to find the Name of God and free him from his curse. I had ventured into the depths of distant Vralia to avenge his wife’s niece.

Of course he would search for Melisande in his sea-mirror.

Word was leaked. The adepts of the Night Court were more than happy to comply.

Gossip whispered in the bedchambers of the Court of Night-Blooming Flowers made its way to the Palace Court and out into Terre d’Ange. The Master of the Straits himself was aiding my quest.

For now the realm was content to watch and wait.

And I was content to be with Sidonie.

We spent the better portion of our days apart. After their long talk, Ysandre didn’t exactly relent, but she thawed considerably. Sidonie had duties, many of them tiresome.

Whenever Ysandre was otherwise committed, she stood in her mother’s stead, hearing suits brought by foreign dignitaries, the quarrels of members of the noble Houses, the complaints of the citizenry.

She had a good head for it. Although she was young—only nineteen, a year past gaining her majority—Sidonie had spent her entire life learning statecraft. She had an acute memory and the ability to recall in a heartbeat the most obscure detail of any legal or historical precedent she’d ever read—and she had read extensively. Supplicants thinking they stood a better chance of swaying the Queen’s young, untried heir were shortly disillusioned.

For my part, I did my best to take on the mantle of responsibility I’d long avoided. I was a peer of the realm, and I had estates I’d neglected all my life. I was a member of Parliament, capable of influencing decisions that had bearing on the whole of Terre d’Ange. I spent a great deal of time simply trying to inform myself. It seemed for every person reluctant to speak with me, there were two others eager to bend my ears in different directions.

Claude de Monluc kept his word, and much to my amused delight, Duc Barquiel L’Envers dispatched the Akkadian-trained captain of his own guard to teach the Dauphine’s Guard how to fight in the saddle. Since he didn’t know me by sight, I was free to take part, posing as a nameless guard among guards. I spent many hours on the drilling-grounds, learning the niceties of cavalry warfare: how to shoot a short bow from the back of a horse at full gallop, how ’twas better to slash and cut on a forward charge than risk lodging one’s blade, how to use one’s mount’s momentum to best advantage and avoid engagement, when to trust blindly to a rearward thrust.

The Bastard loved it. He had the makings of a good warhorse.

And I was good at it. I daresay I had been for a while; as I’d told Claude, I’d spent half my life being taught by Joscelin. Still, it would always be Joscelin against whom I measured myself, and there was no contest. He was better than me. He always would be.

Once I might have cared. I didn’t, not anymore.

Heroism be damned. I wanted only to be sure Sidonie was safe.

Later, at Claude’s request, I asked Joscelin to teach the Dauphine’s Guard a few rudiments of the Cassiline discipline. Not all of it, of course. True Cassiline Brothers begin their training at the age of ten, and for ten years, they do nothing else. Claude’s men were skilled swordsmen in the traditional style, and it would have made no sense for them to unlearn everything they

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher