![Kushiel's Mercy]()

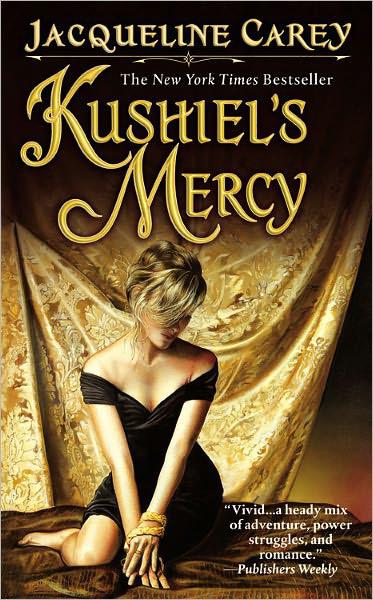

Kushiel's Mercy

his claim about Sidonie, of all people?” She sounded perplexed. “I wouldn’t say they disliked one another, but they’ve never been close.”

“Mayhap that’s why.” The chirurgeon lowered her voice. “The mind is a strange place, my lady, and we cannot examine its workings the way we examine the body’s. I understand he was very ill after his wife was slain and his wounds turned septic. Mayhap one spell of madness evoked another, and somehow in his thoughts, he has replaced the loss of his wife with a loss that is less painful to him.”

Less painful.

Sidonie.

I stared at the moon outside my balcony. A month ago, I’d made love to her by moonlight.

Now she was gone. Gone to Carthage, gone to wed Astegal. Gone of her own volition, it seemed. Was I mad? I had been. I’d said things that made me cringe inside. I didn’t trust myself. But I loved Sidonie. I knew I did. And she loved me. I could feel her absence like a wound. I remembered her. Everything about her. Everything we had done together. Her scent, the taste of her skin. The faraway look she got in the throes of pleasure. Her voice.

Always and always.

My head was full of voices and memory.

Gods, I was tired.

Alais’ voice, her grave face the day we’d spoken atop the ramparts of Bryn Gorrydum . I think she’s going to need you very badly one day.

That damned eunuch, Sunjata.

Go to Cythera.

Ask Ptolemy Solon how to undo what’s done here tonight.

I closed my eyes. “Whatever it is, I’ll do it,” I whispered into the darkness. “I’ll come for you, love. I promise.”

Fourteen

My strength returned slowly.

It wasn’t as bad as it had been after Dorelei’s death. I wasn’t wounded, save for the suppurating abrasions around my wrists and ankles, a bitterly ironic reminder of the bindings I’d once worn as a protection against enchantment. But the fever and lack of nourishment had left me weak.

And I was surrounded by madness.

Everyone in the Palace believed it. Terre d’Ange—and oh, gods, Alba too—had made a pact with Carthage. Sidonie had gone away to wed Astegal, escorted onto the Carthaginian flagship with great fanfare.

No one remembered our affair.

It had been erased from memory as though it had never existed. Mavros came to visit me when he learned I was recovering. I begged him to rack his wits. He had been the first person to know, the one who had helped from the very beginning. All he could do was gaze at me with sympathy and shake his head.

I wanted desperately to get outside the City, but in the first days of my recuperation, I barely had the strength to get out of bed. On Lelahiah Valais’ orders, I was kept in relative solitude. Only family members were permitted to visit me. I wasn’t allowed to hear aught that might disturb me and feed my delusions. Servants and guards were given strict orders not to discuss sensitive matters in my presence.

Still, I heard wisps of conversation here and there, enough to gather that there was widespread dismay beyond the City’s walls. It gave me a thread of hope.

And then, some five days after my fever broke, I overheard a careless guard remark to a chambermaid as she entered my quarters that Ysandre and Barquiel L’Envers were engaged in a shouting match in the throne hall.

L’Envers hadn’t been in the City the night of the full moon.

I struggled into my clothing, trembling with exertion, and made my way into the salon. “I need to talk to him,” I said. “Now.”

“Oh no!” the guard said in alarm. “That’s not possible, your highness.”

“The hell it’s not,” I said. “Get out of my way.”

He blocked me. “Send for Messire Joscelin and Lady Phèdre,” he said urgently to the maid. “They’re in the throne hall with her majesty.”

She nodded and fled.

I found my sword-belt and drew my blade. My arm shook . “Get out of my way.”

The guard put his hands up. “Don’t do this, your highness. You’re ill.”

I gritted my teeth. “I just want to talk to L’Envers. Stand aside, man!”

He did.

I pushed past him, sword in hand. Elua knows, I couldn’t blame them for trying to protect me from myself. The madness had made a monster of me. I would never be able to forget.

But it was gone now, or at least banished into wherever it is that such things lurk in the dark, unplumbed depths of the soul.

At least I prayed it was.

Trailed by the anxious guard, I staggered out of my quarters. Down the hallway, down the wide marble

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher