![Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal]()

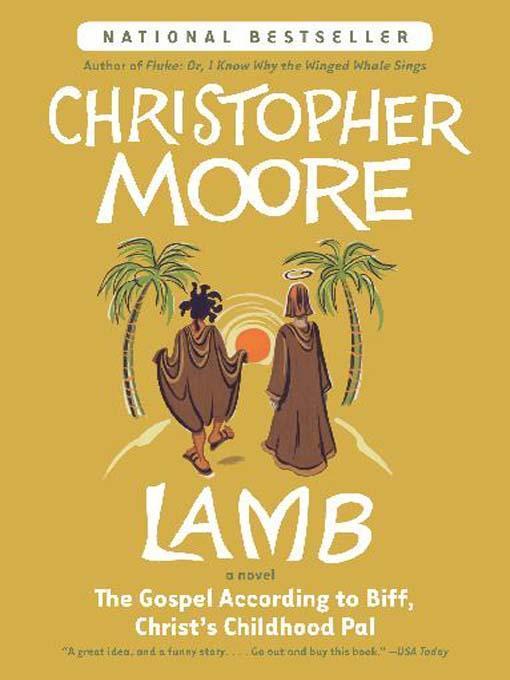

Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal

nature?”

“Please, Gaspar,” Joshua said. “This is a question of practical application, not spiritual growth.” The yeti sighed and licked Josh’s cheek again. I guessed that the creature must have a tongue as rough as a cat’s, as Joshua’s cheek was going pink with abrasion.

“Turn the other cheek, Josh,” I said. “Let him wear the other one out.”

“I’m going to remember this,” Joshua said. “Gaspar, will he harm me?”

“I don’t know. No one has ever gotten that close to him before. Usually he comes while we are in trance and disappears with the food. We are lucky to even get a glimpse of him.”

“Put me down, please,” said Josh to the creature. “Please put me down.”

The yeti set Joshua back on his feet on the ground. By this time the other monks were coming out of their trances. Number Seventeen squealed like a frying squirrel when he saw the yeti so close. The yeti crouched and bared his teeth.

“Stop that!” barked Joshua to Seventeen. “You’re scaring him.”

“Give him some rice,” said Gaspar.

I took the cylinder I had warmed and handed it to the yeti. He popped off the top and began scooping out rice with a long finger, licking the grains off his fingers like they were termites about to make their escape. Meanwhile Joshua backed away from the yeti so that he stood beside Gaspar.

“This is why you come here? Why after alms you carry so much food up the mountain?”

Gaspar nodded. “He’s the last of his kind. He has no one to help him gather food. No one to talk to.”

“But what is he? What is a yeti?”

“We like to think of him as a gift. He is a vision of one of the many lives a man might live before he reaches nirvana. We believe he is as close to a perfect being as can be achieved on this plane of existence.”

“How do you know he is the only one?”

“He told me.”

“He talks?”

“No, he sings. Wait.”

As we watched the yeti eat, each of the monks came forward and put his cylinders of food and tea in front of the creature. The yeti looked up from his eating only occasionally, as if his whole universe resided in that bamboo pipe full of rice, yet I could tell that behind those ice-blue eyes the creature was counting, figuring, rationing the supplies we had brought.

“Where does he live?” I asked Gaspar.

“We don’t know. A cave somewhere, I suppose. He has never taken us there, and we don’t look for it.”

Once all the food was put before the yeti, Gaspar signaled to the other monks and they started backing out from under the overhang into the snow, bowing to the yeti as they went. “It is time for us to go,” Gaspar said. “He doesn’t want our company.”

Joshua and I followed our fellow monks back into the snow, following a path they were blazing back the way we had come. The yeti watched us leave, and every time I looked back he was still watching, until we were far enough away that he became little more than an outline against the white of the mountain. When at last we climbed out of the valley, and even the great sheltering overhang was out of sight, we heard the yeti’s song. Nothing, not even the blowing of the ram’s horn back home, not the war cries of bandits, not the singing of mourners, nothing I had ever heard had reached inside of me the way the yeti’s song did. It was a high wailing, but with stops and pulses like the muted sound of a heart beating, and it carried all through the valley. The yeti held his keening notes far longer than any human breath could sustain. The effect was as if someone was emptying a huge cask of sadness down my throat until I thought I’d collapse or explode with the grief. It was the sound of a thousand hungry children crying, ten thousand widows tearing their hair over their husbands’ graves, a chorus of angels singing the last dirge on the day of God’s death. I covered my ears and fell to my knees in the snow. I looked at Joshua and tears were streaming down his cheeks. The other monks were hunched over as if shielding themselves from a hailstorm. Gaspar cringed as he looked at us, and I could see then that he was, indeed, a very old man. Not as old as Balthasar, perhaps, but the face of suffering was upon him.

“So you see,” the abbot said, “he is the only one of his kind. Alone.”

You didn’t have to understand the yeti’s language, if he had one, to know that Gaspar was right.

“No he’s not,” said Joshua. “I’m going to him.”

Gaspar took

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher