![Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal]()

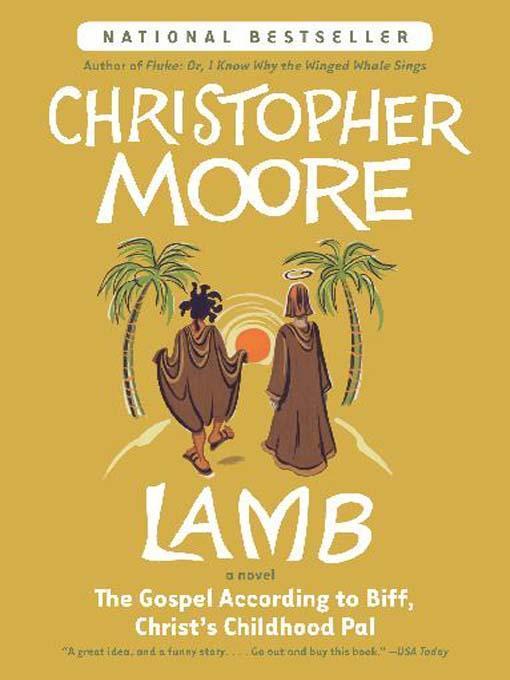

Lamb: the Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal

the morning in the monastery and I could see our breath as Gaspar boiled the water for tea. Soon I saw a third puff of breath coming from my side of the table, although there was no person there.

“Good morning, Joshua,” Gaspar said. “Did you sleep, or are you free from that need?”

“No, I don’t need sleep anymore,” said Josh.

“You’ll excuse Twenty-one and I, as we still require nourishment.”

Gaspar poured us some tea and fetched two rice balls from a shelf where he kept the tea. He held one out for me and I took it.

“I don’t have my bowl with me,” I said, worried that Gaspar would be angry with me. How was I to know? The monks always ate breakfast together. This was out of order.

“Your hands are clean,” said Gaspar. Then he sipped his tea and sat peacefully for a while, not saying a word. Soon the room heated up from the charcoal brazier that Gaspar had used to heat the tea and I was no longer able to see Joshua’s breath. Evidently he’d also overcome the gastric distress of the thousand-year-old egg. I began to get nervous, aware that Number Three would be waiting for Joshua and me in the courtyard to start our exercises. I was about to say something when Gaspar held up a finger to mark silence.

“Joshua,” Gaspar said, “do you know what a bodhisattva is?”

“No, master, I don’t.”

“Gautama Buddha was a bodhisattva. The twenty-seven patriarchs since Gautama Buddha were also bodhisattvas. Some say that I, myself, am a bodhisattva, but the claim is not mine.”

“There are no Buddhas,” said Joshua.

“Indeed,” said Gaspar, “but when one reaches the place of Buddhahood and realizes that there is no Buddha because everything is Buddha, when one reaches enlightenment, but makes a decision that he will not evolve to nirvana until all sentient beings have preceded him there, then he is a bodhisattva. A savior. A bodhisattva, by making this decision, grasps the only thing that can ever be grasped: compassion for the suffering of his fellow humans. Do you understand?”

“I think so,” said Joshua. “But the decision to become a bodhisattva sounds like an act of ego, a denial of enlightenment.”

“Indeed it is, Joshua. It is an act of self-love.”

“Are you asking me to become a bodhisattva?”

“If I were to say to you, love your neighbor as you love yourself, would I be telling you to be selfish?”

There was silence for a moment, and as I looked at the place where Joshua’s voice was originating, he gradually started to become visible again. “No,” said Joshua.

“Why?” asked Gaspar.

“Love thy neighbor as thou lovest thyself”—and here there was a long pause when I could imagine Joshua looking to the sky for an answer, as he so often did, then: “for he is thee, and thou art he, and everything that is ever worth loving is everything.” Joshua solidified before our eyes, fully dressed, looking no worse for the wear.

Gaspar smiled and those extra years that he had been carrying on his face seemed to fade away. There was a peace in his aspect and for a moment he could have been as young as we were. “That is correct, Joshua. You are truly an enlightened being.”

“I will be a bodhisattva to my people,” Joshua said.

“Good, now go shave the yak,” said Gaspar.

I dropped my rice ball. “What?”

“And you, find Number Three and commence your training on the posts.”

“Let me shave the yak,” I said. “I’ve done it before.”

Joshua put his hand on my shoulder. “I’ll be fine.”

Gaspar said: “And on the next moon, after alms, you shall both go with the group into the mountains for a special meditation. Your training begins tonight. You shall receive no meals for two days and you must bring me your blankets before sundown.

“But I’ve already been enlightened,” protested Josh.

“Good. Shave the yak,” said the master.

I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised when Joshua showed up the next day at the communal dining room with a bale of yak hair and not a scratch on him. The other monks didn’t seem surprised in the least. In fact, they hardly looked up from their rice and tea. (In my years at Gaspar’s monastery, I found it was astoundingly difficult to surprise a Buddhist monk, especially one who had been trained in kung fu. So alert were they to the moment that one had to become nearly invisible and completely silent to sneak up on a monk, and even then simply jumping out and shouting “boo”

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher