![Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row]()

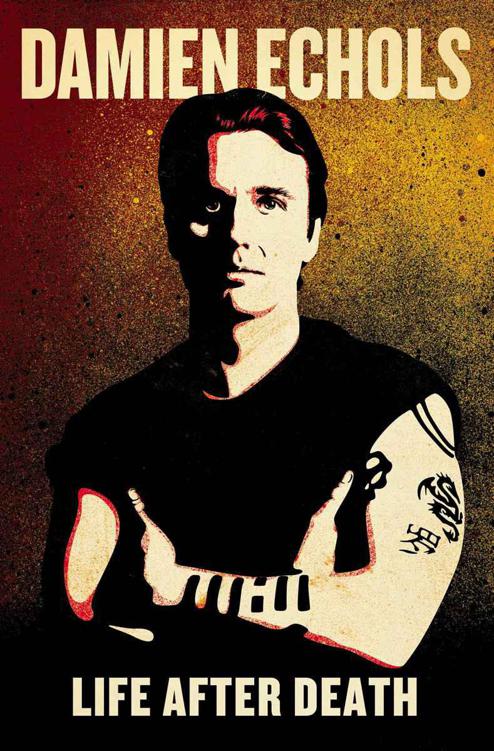

Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row

ceremony. The altar cloth was white silk, and on it was a small Buddha statue, a canvas covered with calligraphy, and an incense burner. We all dropped a pinch of the exotic-smelling incense into the burner as an offering, and then opened our sutra books to begin the proper chants. Kobutsu had to help me turn the pages of my book because the guards made me wear chains on my hands and feet. During the course of the ceremony I was given the name Koson. I loved that name and all it symbolized, and scribbled it everywhere. I was also presented with my rakusu.

A rakusu is made of black cloth, and is suspended from your neck. It covers your hara, which is the energy center about two finger-widths below your belly button. It has two black cloth straps and a wooden ring/buckle. It’s sewn in a pattern that looks like a rice paddy would if viewed from the air. It represents the Buddha’s robe. This is the only part of my robe the administration would allow me to keep inside the prison. On the inside, Harada Roshi had painted beautiful calligraphy characters that said, “Great effort, without fail, brings great light.” It was my most prized possession until the day years later when the prison guards took it from me.

The canvas on the altar was also given to me. Its calligraphy translates to “Moonbeams pierce to the bottom of the pools, yet in the water not a trace remains.” I proudly put it on display in my cell.

I ventured into the realm of Zen to gain a handle on my negative emotional states, which I had learned to control to a great extent, but I now approached my practice in a much more aggressive manner. Much like a weight lifter, I continued to pile it on. On weekends I was now sitting zazen meditation for five hours a day. My prayer beads were always in my hand as I constantly chanted mantras. I practiced hatha yoga for at least an hour a day. I became a vegetarian. Still, I did not have a breakthrough Kensho experience. Kensho is a moment in which you see reality with crystal-clear vision, what a lot of people refer to as “enlightenment.” I didn’t voice my thoughts out loud, but I was beginning to harbor strong suspicions that Kensho was nothing more than a myth.

A teacher of Tibetan Buddhism started coming to the prison once a week to instruct anyone interested. I attended these sessions, which were specifically tailored to be of use to those on Death Row. One practice I and another inmate were taught is called Phowa. It consists of pushing your energy out through the top of your head at the moment of death. It still did not bring about that life-changing moment I was in search of.

Two

M y memory really starts to come together and form a narrative once I started school. I can still remember every teacher I ever had, from kindergarten through high school.

My parents, sister, and I moved into an apartment complex called Mayfair in 1979, as far as I recall. We had an upstairs apartment in a long line of identical doors. When I went out to play, I could find my way back home only by peeking in every window until I saw familiar furnishings. My grandmother also moved into an apartment in the complex, one row behind us. This was the year I started kindergarten, and I remember it well.

Mayfair was located in a run-down section of West Memphis, Arkansas, although not nearly as run-down as it would later become. We were in the worst school district in the city, and on the first day I saw that I was one of only two white kids in the entire class. The other was my best friend, Tommy, who also lived in Mayfair. Our teacher was a skinny black woman named Donaldson, and I’d be hard-pressed to find a more hateful adult. She wasn’t as bad to the girls, but seemed to harbor an intense hatred for all male children. I honestly don’t know how she ever became a teacher, as she seemed to spend all her time racking her brain to come up with new and innovative forms of punishment.

I was very quiet at this age, almost to the point of being invisible. I managed to avoid her wrath most of the time, but twice she noticed me. Once, for a reason I never understood, a girl told her that I had my eyes open during nap time. Every day after lunch we were to pull out our mats, lie on the floor, and sleep for half an hour while the teacher left us alone. No one knew where she went or why. For her it was not enough that we lay still, she wanted us to sleep, and expected us to do so on command. She would appoint one person to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher