![Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row]()

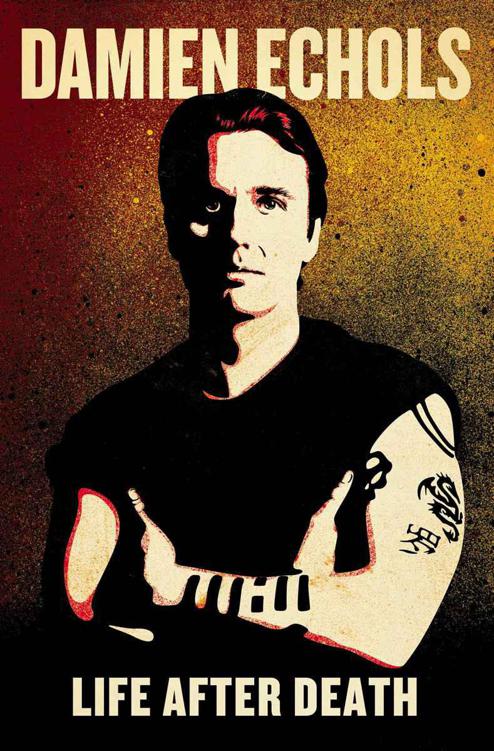

Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row

and telling me about their progress. I found out later that they were being paid by the court and hadn’t in fact done anything beyond what any investigator is obliged to do in this situation. But on my birthday Glori even brought me a box of cupcakes. We sat alone in a small office eating cake and going over the case. She gave me hope. What I’ve discovered in the years since then is that this is their job, to give hope. It’s a ploy, really, because they are just as much a part of the predetermined courtroom defense formula.

* * *

O n January 26, 1994, Jessie went to trial. I watched news coverage from my cell—it was utterly painful to see. Jessie’s false confession was the centerpiece of the proceedings—it was the only so-called evidence the prosecutor, John Fogleman, had. It cemented our guilt in everyone’s mind and ensured our conviction before we could go on trial ourselves. On the eighth day, Jessie was convicted and sentenced to life plus two twenty-year sentences.

We were also being made the subjects of an HBO documentary. On June 5, the day after the West Memphis police held a press conference to announce they had caught the alleged perpetrators of the crime, an HBO executive named Sheila Nevins saw an article half-buried in

The New York Times

and shared it with two filmmakers, Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky. The headline, “3 Arkansas Youths Are Held in Slayings of 3 8-Year-Olds,” offered the potential for a provocative and salacious film about Satanism, human sacrifice, and debauchery of gothic proportion. Joe and Bruce immediately took a production crew to West Memphis and began interviewing locals, the parents of the victims, my friends and acquaintances, my family, Jason’s family, and Jessie’s. What began to emerge for them was a far different picture of the circumstances. Joe and Bruce both acknowledged that after speaking with locals, it was clear to them that the three of us were being put on trial for crimes we didn’t commit.

A few weeks before my trial, I was transferred to Craighead County jail in the town of Jonesboro—ostensibly, I was moved there to be closer to my lawyers, so we could strategize in the weeks before my trial. It was nothing like the Monroe County jail. The guards were all cruel and abusive. They talked to you as if addressing a lower life form, no matter how polite and civil you were to them. I witnessed them beating prisoners on an almost daily basis. Years later, as I was lying in my cell on Death Row watching the news, I saw that five guards had been fired in Jonesboro because they had handcuffed a prisoner and beat him unconscious. They were fired. No charges were filed against them. Most of the time they’re not even fired, only demoted. If you walk up to a man on the street and punch him in the face, you go to prison for assault. Do the same thing to a man in prison and you get demoted.

There was a small Mexican guy in jail there who suffered from catatonic schizophrenia. He would sit or stand in odd positions for hours at a time because of his mental illness. The guards would beat him just to see if they could make him move. It was a game to them. They often spit in your food to see if they could get you to fight. If you said anything at all, they’d call in five or six of their friends to beat you. Once you’re behind the walls, there is no help. The world doesn’t care.

In Jonesboro, I was put in a cell block by myself. There was no one to talk to, no books to read, no television to watch, and no going outside. I was locked in an empty concrete vault all day and night. I knew Jason was in the next cell block, because it was so noisy I could hear the guys on that side through the wall. He was on a block with about ten other people. It would have been a huge comfort to be able to sit in the same room with him and talk, perhaps try to figure out what went wrong, but the guards made certain we never even saw each other.

I slipped deeper and deeper into despair. Without a miracle we would die in prison. Jason and I were scheduled to go to trial together, though the attorneys were all fighting tooth and nail. Jason’s attorneys wanted a separate trial for him, to remove him somehow from my already established guilt. It seemed like the entire world was howling for my blood.

Twenty-one

F ebruary 19, 1994, the first morning of our trial, Jason and I were given bulletproof vests to wear to and from the courthouse. Emotions were running

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher