![Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row]()

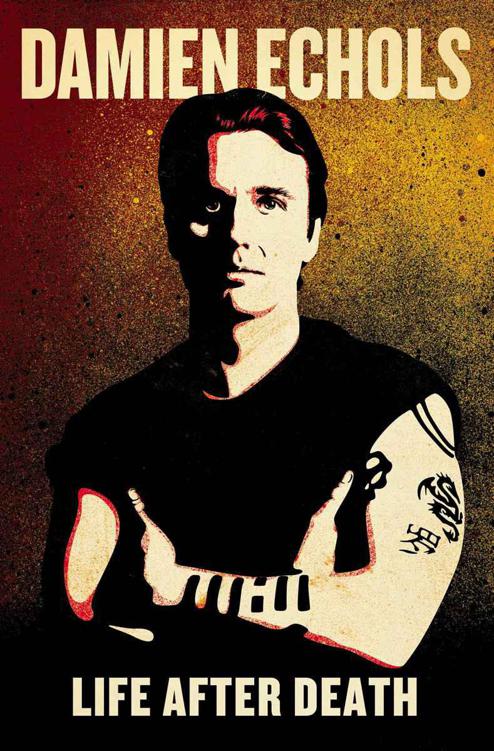

Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row

but getting a stay of execution is automatic.” I’d like to see how well they’d laugh it off if it was their names on a piece of paper with a date next to it. Har har har, you jokers. That’s a good one.

My attorneys were so incompetent that they didn’t realize a motion needed to be filed in order to obtain a stay of execution. They found out before it was too late, but just by a hair. I managed to have a phone conversation with Glori, who told me that somehow one of them had discovered the oversight at the last minute.

Most people who go to prison first stay at what is called the Diagnostic Center. That’s where they give you a complete physical and mental evaluation. Jason was there for about three weeks, I believe, and Jessie was there for the better part of a year, at least. If you’re going to Death Row, there’s no layover at the Diagnostic Center. What would be the point? Physical health and mental health don’t really matter if you’re going to be standing before a firing squad. I went straight to the big house itself.

It was dark outside when we pulled up, but the place was still lit up like a Christmas tree. The lights are never turned completely off in prison, and there are searchlights constantly moving to and fro. I was taken out of the car and into the base of the guard tower behind the prison building, where I was strip-searched and given a pair of “prison whites.” That’s what they call the uniform you’re issued.

There was some fat clown in polyester pants, a short-sleeved shirt, and clip-on tie issuing orders. His air of self-importance would lead you to believe he was a warden or something. He had a horrendous little boy’s haircut and the requisite seventies porn mustache. He was not the warden. During the first week, another prisoner told me he was assigned to the mental health division and had no authority whatsoever. And since there is no budget, no resources or structured mental health services for Death Row inmates, he had no professional reason for being there anyway.

That’s a common thing in the prison industry: take some losers who have spent their life bagging groceries or asking, “Would you like fries with that?” and put them in polyester guard uniforms, and they blow up like puffer fish and march around like baby Hitlers. This is the only place they can feel important, so they fall in love with the job. It becomes their life, and they’d rather die than lose it.

The clown screamed in my face, “Your number is SK931! Remember it!” At that moment, I happened to glance at a digital clock, which read 9:31 p.m. I wondered if everyone’s number was the same as the time they came in. (It was just a very bizarre coincidence.) A nurse checked my temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate. They seemed to find it hilarious that my pulse registered like that of a rabbit’s in a snare.

After they finished, I was taken to a filthy, rat-infested barracks that contained fifty-four cells. Death Row. You’d be amazed at how many letters I’ve gotten from people who say they’re sorry I’m on “Death Roll.” I always picture that thing an alligator does when it grabs you and starts spinning around and around. It rips you to shreds and drowns you at the same time. The death roll. I was put in cell number four, and immediately fell asleep. I was exhausted from the trauma. Shutting down was the only way my mind could preserve itself.

I think my first phone call was to my parents, to let them know that I was alive. I don’t remember when I made that call, because the phone system at the time was so convoluted. You had to fill out paperwork just to make a five-minute call. It took about a week for the paperwork to be reviewed and then approved or not. It’s vastly different now, because the prison system has an agreement with a phone company to split the charges on any call; now, anyone can make a call just about anytime they want, as long as you can afford it. The prison profits enormously; a fifteen-minute call can cost you about twenty-five dollars.

When I arose from my concrete slab to begin my first full day of prison life, I noticed someone had dropped a package in my cell. Opening it, I saw that it contained a couple of stamped envelopes, a pen and some paper, a can of shaving cream, a razor, a chocolate cupcake, a grape soda, and a letter of introduction. The letter was from a guy upstairs named Frankie Parker. No one called him by that name, though.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher