![Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row]()

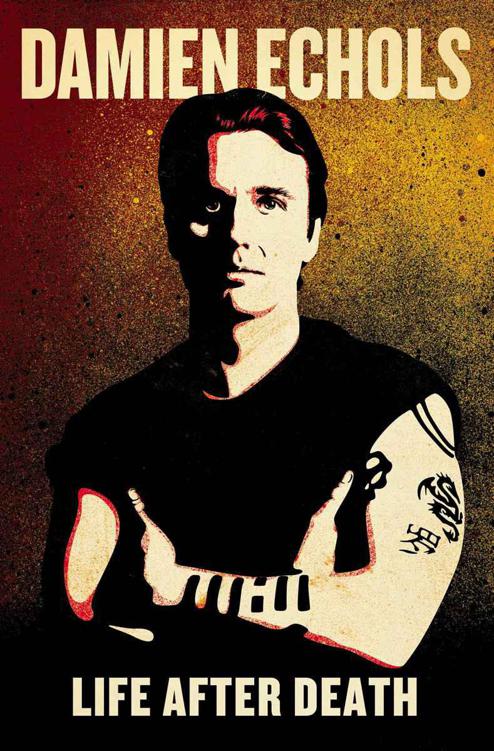

Life After Death: The Shocking True Story of a Innocent Man on Death Row

afterward I would walk around in a daze, thinking to myself,

What kind of world is this where such things happen?

The only thing that’s ever affected me the same way was footage on the TV news of Iraqi terrorists beheading an American hostage. It’s hard to comprehend that such things still take place in this day and age.

As for Kurt, he didn’t look much better than the two guards once it was all over. When I was really young—about nine or ten years old—my stepfather took me on a form of hunting expedition called “frog-gigging.” My stepfather, stepbrother, brother-in-law, and I would go out at night into the swamp and float silently in a twelve-foot boat. I was the light man. This means while the other three were armed with implements that looked like extremely long pitchforks, I was in charge of sweeping a spotlight up and down the banks to find the frogs. I never was much good at it, because I found the whole affair to be entirely repulsive with not a single redeeming quality. At any rate, by the time twenty guards were finished beating Kurt to a pulp, he looked like a team of frog-giggers had been at him. That’s what I thought of every time I saw him after that. In my mind I saw him as a giant bullfrog. They had beaten him so badly it looked like he had two heads. It was even worse than it sounds. They tortured him right up until his death. You could see fear in their eyes because of what he had done to the two guards. They were so scared of him that they would go out of their way to appear unafraid. I’ll never forget it for as long as I live. What makes it all worse for me is that I know I should never have been sent here to witness it in the first place.

Twenty-three

T he crew from HBO were still working on the documentary they’d started before we went on trial. I had mostly forgotten about it after I had been in prison for a year or so, thinking nothing had come of it. They had interviewed me, Domini, my family, the cops, the victims’ families, and anyone else who would talk. They had also filmed the entire trial, from beginning to end. I didn’t see the documentary when it finally aired in 1996, but many other people around the world did.

On a daily basis I started receiving letters and cards from people all over the country who had seen the film

Paradise Lost

, and were horrified by it. The overwhelming sentiment was, “That could have been me they did that to!” If you are to understand the impact this had on me, you have to understand that up until that point I had received no sympathy or empathy from anyone. Everywhere I turned, I found nothing but disgust, contempt, and hatred. The whole world wanted me to die. It’s impossible to have any hope in the face of such opposition. Now I was suddenly receiving letters from people saying, “I’m so sorry for what was done to you. I wish there was something I could do to help.”

A single letter like that would have been enough to kindle a tiny spark of hope in my heart, but I received hundreds. Every day at least one or two would arrive, sometimes as many as ten or twenty. I would lie on my bunk and flip through the letters, savoring them like a fat kid with a fistful of candy, whispering, “Thank you. . . . Thank you,” over and over again. I clutched those letters to my chest and slept with them under my head. I had never been so thankful for anything in my entire life.

I don’t want a “holy” life of prayer and contemplation. I want a life of strife, lust, striving, seeking, struggling, and debauchery. I’m not content to settle for one experience when there is a whole lifetime of experiences to be had. I am so hungry for knowledge that I live several lives at once to acquire it. A Catholic and a Buddhist, a reader and a writer, a sinner and a philosopher, a husband and a father, a Native American and a white man—I no longer have any desire to fit into any one category. I see no reason why I can’t love pornography and the art of Michelangelo equally. I want to see life from every angle. I feel as if I’ve learned a tremendous amount from my excursion into the realm of Eastern thought, philosophy, and practice—things I’ll carry with me to the end of my days. Still, it doesn’t come close to the lessons I’ve learned from, and with, the woman who is now my wife.

I had been on Death Row for about two years when I received an odd letter in the mail, in February 1996. It was from a woman who loved movies and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher