![Lords and Ladies]()

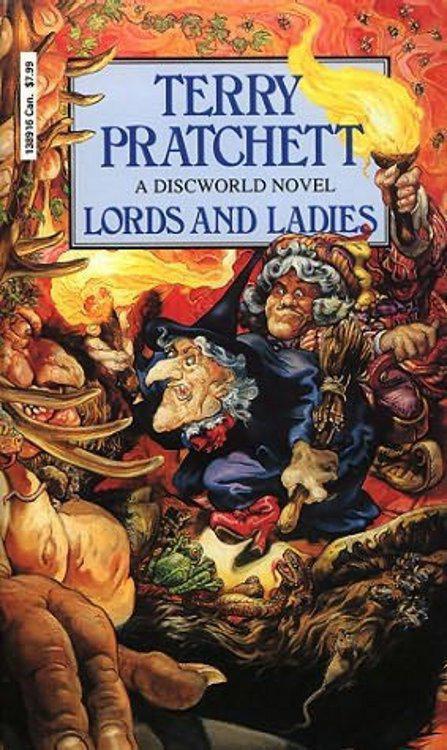

Lords and Ladies

elves could run faster.

He bounced over logs and skidded through drifts of leaves, aware even as his vision fogged that elves were overtaking him on either side, pacing him, waiting for him to…

The leaves exploded. The little god was briefly aware of a fanged shape, all arms and vengeance. Then there were a couple of disheveled humans, one of them waving an iron bar around its head.

Herne didn’t wait to see what happened next. He dived through the apparition’s legs and ran on, but a distant warcry echoed in his long, floppy ears:

“Why, certainly, I’ll have your whelk! How do we do it? Volume!”

Nanny Ogg and Casanunda walked in silence back to the cave entrance and the flight of steps. Finally, as they stepped out into the night air, the dwarf said, “Wow.”

“It leaks out even up here,” said Nanny. “Very mackko place, this.”

“But I mean, good grief—”

“He’s brighter than she is. Or more lazy,” said Nanny. “He’s going to wait it out.”

“But he was—”

“They can look like whatever they want, to us,” said Nanny. “We see the shape we’ve given ’em.” She let the rock drop back, and dusted off her hands.

“But why should he want to stop her?”

“Well, he’s her husband, after all. He can’t stand her. It’s what you might call an open marriage.”

“Wait what out?” said Casanunda, looking around to see if there were anymore elves.

“Oh, you know,” said Nanny, waving a hand. “All this iron and books and clockwork and universities and reading and suchlike. He reckons it’ll all pass, see. And one day it’ll all be over, and people’ll look up at the skyline at sunset and there he’ll be.”

Casanunda found himself turning to look at the sunset beyond the mound, half-imagining the huge figure outlined against the afterglow.

“One day he’ll be back,” said Nanny softly. “When even the iron in the head is rusty.”

Casanunda put his head on one side. You don’t move around among a different species for most of your life without learning to read a lot of their body language, especially since it’s in such large print.

“You won’t entirely be sorry, eh?” he said.

“Me? I don’t want ’em back! They’re untrustworthy and cruel and arrogant parasites and we don’t need ’em one bit.”

“Bet you half a dollar?”

Nanny was suddenly flustered.

“Don’t you look at me like that! Esme’s right. Of course she’s right. We don’t want elves anymore. Stands to reason.”

“Esme’s the short one, is she?”

“Hah, no, Esme’s the tall one with the nose. You know her.”

“Right, yes.”

“The short one is Magrat. She’s a kind-hearted soul and a bit soft. Wears flowers in her hair and believes in songs. I reckon she’d be off dancing with the elves quick as a wink, her.”

More doubts were entering Magrat’s life. They concerned crossbows, for one thing. A crossbow is a very useful and usable weapon designed for speed and convenience and deadliness in the hands of the inexperienced, like a faster version of an out-of-code TV dinner. But it is designed to be used once, by someone who has somewhere safe to duck while they reload. Otherwise it is just so much metal and wood with a piece of string on it.

Then there was the sword. Despite Shawn’s misgivings, Magrat did in theory know what you did with a sword. You tried to stick it into the enemy by a vigorous arm motion, and the enemy tried to stop you. She was a little uncertain about what happened next. She hoped you were allowed another go.

She was also having doubts about her armor. The helmet and the breastplate were OK, but the rest of it was chain-mail. And, as Shawn Ogg knew, chain-mail from the point of view of an arrow can be thought of as a series of loosely connected holes.

The rage was still there, the pure fury still gripped her at the core. But there was no getting away from the fact that the heart it gripped was surrounded by the rest of Magrat Garlick, spinster of this parish and likely to remain so.

There were no elves visible in the town, but she could see where they had been. Doors hung off their hinges. The place looked as though it had been visited by Genghiz Cohen. *

Now she was on the track that led to the stones. It was wider than it had been; the horses and carriages had churned it on the way up, and the fleeing people had turned it into a mire on the way down.

She knew she was being watched, and it almost came as a relief when

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher