![Murder at Mansfield Park]()

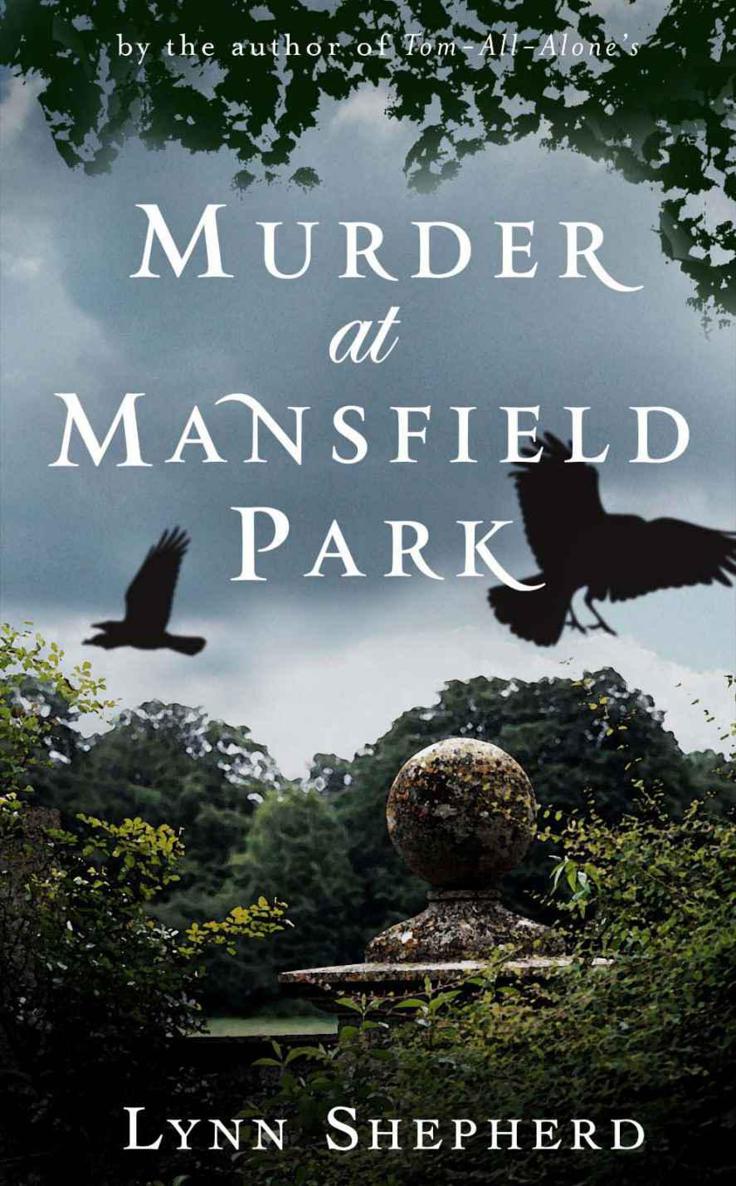

Murder at Mansfield Park

the certainty of a more eligible offer to break off an engagement that had now become a source of regret and disappointment, however public the rupture must prove to

be.

The eyes of everyone present were still fixed on Miss Price, and only Mary was so placed as to see the expression of shock and alarm on Mrs Norris’s face. It was apparent at once that she

was under the influence of a tumult of new and very unwelcome ideas. She looked almost aghast, but it was not the arrival of her son that was the cause of it; for many weeks now she had considered

Mary to be the principal threat to a union that she had looked forward to for so long, and which was even now on the point of accomplishment. But in devoting so much energy to hindering Mary, and

disparaging her, she had entirely overlooked another, and far more insidious development. There was now no room for error. The conviction that had rushed over her mind, and driven the colour from

her cheeks, could no longer be denied: the true daemon of the piece was not the upstart, under-bred Mary, but the smooth and plausible Mr Rushworth, a man she had been flattering and encouraging

all the while, thinking him to be the admirer of Maria, and a good enough match for her and her seven thousand pounds. But now Mrs Norris’s eyes were opened, and her fury and indignation were

only too evident.

‘If I must say what I think,’ she said, in a cold, determined manner, ‘it is very disagreeable to be always rehearsing. I think we are a great deal better employed,

sitting comfortably here among ourselves, and doing nothing.’

Edmund replied with an increase of gravity which was not lost on anyone present, ‘I am happy to find our sentiments on this subject so much the same, madam. There will be no more

rehearsals.’

There was indeed no question of resuming. Mr Rushworth clearly considered it as only a temporary interruption, a disaster for the day, and even suggested the possibility of the rehearsal being

renewed after tea. But to Mary, the conclusion of the play was a certainty; the total cessation of the scheme was inevitably at hand, and the tender scene between herself and Mr Norris would go no

further forward.

CHAPTER VII

The price to be paid for the doubtful pleasure of private theatricals was in Mary’s thoughts the whole of the following day, and an evening of backgammon with Dr Grant

was felicity to it. It was the first day for many, many days, in which the households had been wholly divided. Four-and-twenty hours had never passed before, since April began, without bringing

them all together in some way or other. At the Park the evening passed with external serenity, though almost every mind was ruffled, and the music which Lady Bertram called for from Julia helped to

conceal the want of real harmony. Maria kept to her room, complaining of a cold, while Fanny sat quietly with her needle, a smile of secret delight now and again playing about her lips. In the more

retired seclusion of the White House, Mrs Norris gave way to a bitter invective against Rushworth, inciting her son to exert himself, it being within his power to remedy all these evils, if he

would but act like a man, with fortitude and resolution. Edmund’s private feelings in the face of such a tirade may only be guessed at.

‘I was sorry to hear that the play is done with,’ said Mrs Grant, when Henry and Mary joined her and Dr Grant in the breakfast-room the next morning. ‘The

other young people must be very much disappointed.’

‘I fancy Yates is the most afflicted,’ said Henry with a smile. ‘He is gone back to Bath, but, he said, if there was any prospect of a renewal of Lovers’ Vows, he

should break through every other claim. “From Bath, London, York, Heath Row—wherever I may be,” he announced, “I will attend you from any place in England, at an

hour’s notice.”’ ‘I confess I did wonder at the Heath Row,’ he continued, helping himself to more chocolate. ‘Indeed I was not even sure at the time where he

meant. It appears it is a small village some where to the west of London. Yates is thinking of buying a place there, but by all accounts the area is damp, low-lying and disposed to fog, and I

therefore gave it as my opinion that it was unlikely much would ever be made of it.’

‘Still,’ said Mrs Grant, returning to the subject of the lost theatricals, ‘there will be little rubs and disappointments every where, but then, if one plan

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher