![Murder at Mansfield Park]()

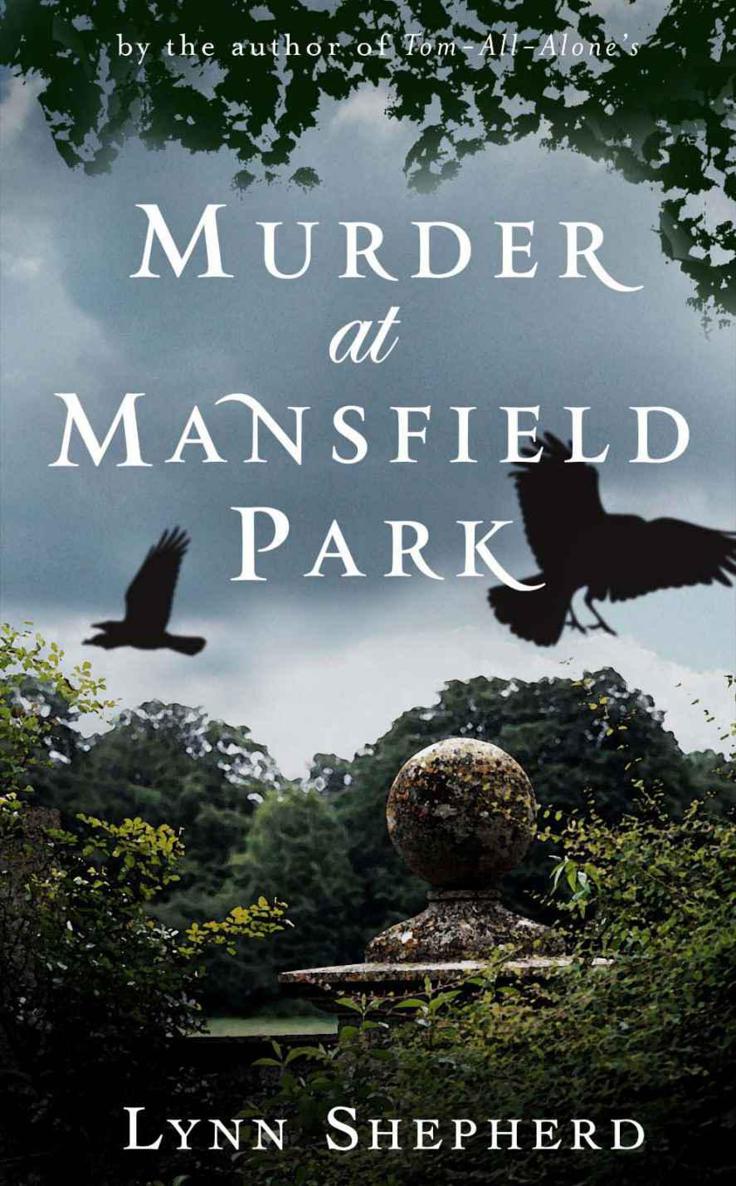

Murder at Mansfield Park

ill-mannered. Maddox smiled to himself—these fine ladies and

gentlemen! It was not the first time that he had seen one of their class imprisoned by the iron constraints of politeness and decorum.

‘To tell you the truth, I followed you here, precisely so that we might have this chance to talk privately,’ he continued. ‘I wished to elucidate one or two points, but felt

that you would prefer to discuss these matters when the rest of your family were not present.’

He received a side-glance at this, but nothing more.

‘You stated, just now, that you remained in your own room for the whole morning on Tuesday last, and that your maid was with you. You still hold to that? There is nothing you wish to

add—or, perhaps, modify?’

‘No,’ she said, her colour rising. ‘I have told you every thing you need to know.’

‘I fear,’ he said, with a shake of the head, ‘that that is not the case. But let us leave the matter there for the moment. Why are you so concerned that your sister may soon be

in a position to speak to me?’

A slight change in his tone ought to have been warning enough, but she had not heeded it.

‘I—I—do not know what you mean,’ she stammered, her face like scarlet.

‘It is not wise to trifle with me, Miss Bertram, and even more foolish to attempt to deceive me. I saw it with my own eyes only a few minutes ago. Mr Gilbert told you that Miss Julia may

soon be recovered enough to speak, did he not? I saw the effect this intelligence had upon you—and how intent you were to disguise it.’

‘How could you possibly—’

Maddox smiled. ‘Logic and observation, Miss Bertram, logic and observation. They are, you might say, the tools of my trade. Mr Gilbert had good news, that much was obvious; ergo ,

your sister is recovering. And if your sister is recovering, she will soon be able to speak. This intelligence clearly disturbs you; ergo , you must fear what it is she is likely to say.

Simple, is it not?’

She was, by now, breathless with agitation, and had her handkerchief before her face. ‘I am not well,’ she said weakly, attempting to rise, ‘I must return to the

house.’

‘All in good time,’ said Maddox. ‘Let us first conclude our discussion. You may, perhaps, find that it is not quite as alarming as you fear at this moment. But I have taken the

precaution of providing myself with salts. I have had need of them on many other like occasions.’

Maria took them into her own hands, and smelling them, raised her head a little.

‘You are a villain, sir—not to allow a lady on the point of fainting—’

‘Not such a villain as you may at present believe. But no matter; I will leave it to your own conscience to dictate whether you do me an injustice on that score. But to the point at hand.

I will ask you the question once again, and this time, I hope you will answer me honestly. I can assure you, for your own sake, that this would be by far the most advisable way of

proceeding.’

She hesitated, then acquiesced, her hands twisting the handkerchief in her lap all the while.

‘Good. So I will ask you once more, what is it that you fear your sister will divulge?’

A pause, then, ‘She heard me tell Fanny that I wished she were dead.’

‘I see. And when was this?’

‘At Compton. The day we visited the grounds.’

Maddox nodded, more to himself than to his companion, whose eyes were still fixed firmly on the ground; one piece of the puzzle had found its correct place.

‘I was—angry—with Fanny,’ she continued, ‘and I spoke the words in haste.’ Her voice dropped to barely a whisper. ‘I did not mean it.’

Maddox smiled. ‘I am sure we all say such things on occasion, Miss Bertram, and from what I hear, your cousin was not, perhaps, the easiest person to live with, even in a house the size of

this. Why should such idle, if unfortunate words have caused you so much anxiety?’

It was his normal practice to ask only those questions to which he had already ascertained the answer, and this was no exception; but even the most proficient physiognomist would have been hard

put to it to decide whether the terror perceptible in the young woman’s face was proof of an unsophisticated innocence—or the blackest of guilt.

Maria put her handkerchief to her eyes. ‘After Fanny and I quarrelled in the wilderness I ran away—but—but—my eyes were full of tears and I could hardly see. I stumbled

on the steps leading up to the lawn,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher