![Murder at Mansfield Park]()

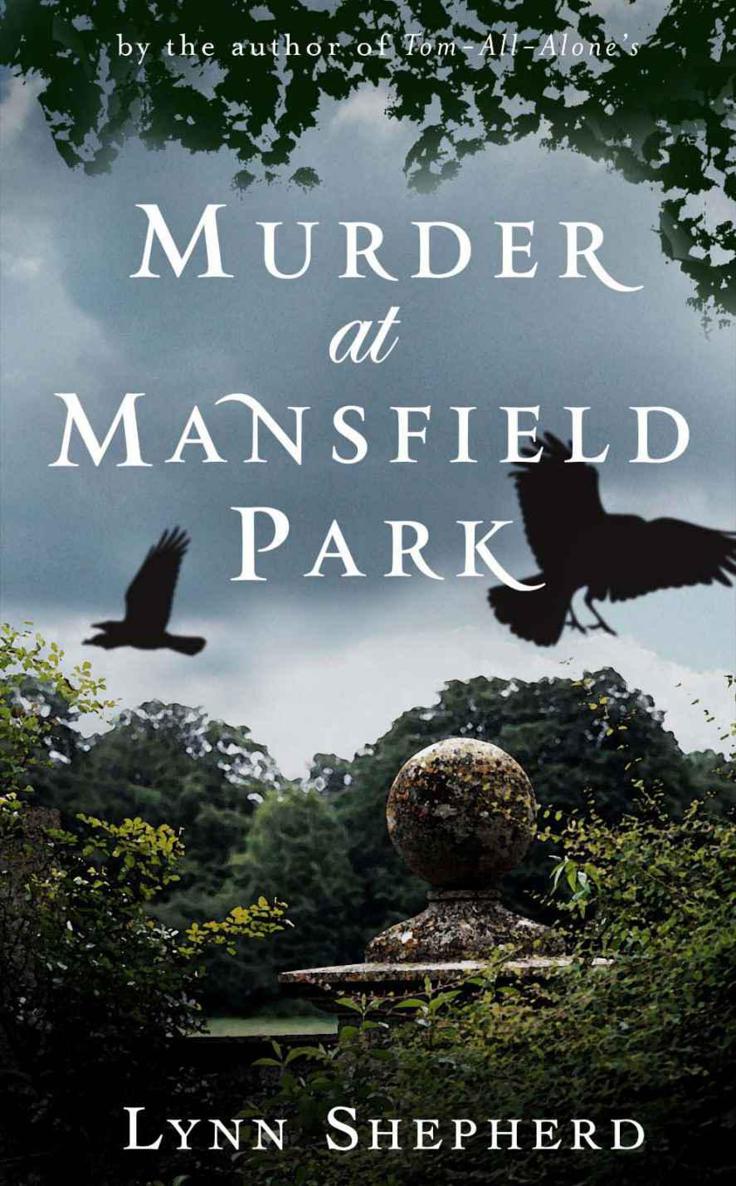

Murder at Mansfield Park

her, and she slipped into a shallow and disturbed slumber, only to wake at dawn in a terror that made such an impression upon her, as almost

to overpower her reason. She had fallen into a dark and wandering dream, in which she was barefoot, walking across the park, as the mist rose from the hollows, and the owls shrieked in the dark

trees. All at once she found herself at the edge of the channel—the dank and fetid pit yawned beneath her very feet. She was overcome with fear, and dared not go any farther, but some thing

drew her on, and she saw with revulsion that the body was still there at the bottom of the chasm, still wrapped in its crimson cloak and bloody dress, the face already rotting, and maggots eating

at the suppurating flesh. She turned away, sickened, but Maddox stood behind her, and took hold of her arm, forcing her to look, forcing her to the very brink. And now she saw that Henry and Edmund

were standing at either end of the trench—she saw them face each other, their countenances blank of all expression, then draw their swords with a rasp of polished metal. Minute after minute

they fought over the body, notwithstanding all her prayers and tears, trampling the dissolving carcase beneath their feet, and staining their shirts with runnels of blood that smoked in the cold

air. Then in the space of a moment, Henry was suddenly in the ascendant, pinning his opponent against the earth, and holding his sword across Edmund’s throat; Mary cried out, ‘No!

No!’ and as her brother looked up to where she stood, Edmund drew back his sword, and ran his rival through the thigh. Henry slipped to his knees, his eyes all the while on Mary’s face,

fixing her with a look of unutterable agony and reproach. She turned to Edmund for mercy, but he rejected her pleas with arrogant disdain, and pushed the point of his sword slowly, slowly through

his adversary’s heart. She crawled towards him, as Maddox threw earth and dirt down upon her dying brother, and the rotting corpse of his dead wife; then she awoke in a cold sweat, real tears

on her cheeks, and the frightful images still before her eyes.

She did not know how long it was she lay there, trembling and weeping, before she felt able to sit up. It was still dark outside. She had never given any credence to dreams, deeming them to be

but the incoherent vagaries of the sleeping mind, and no prognostic or prophecy of what was to come; but while her intellect might attribute her vision to the uneasiness of a weakened and disturbed

constitution, her conscience told her otherwise. Her imagination had forced her to contemplate the true nature of the choice she must now make; her heart shrank from the dread prospect, but her

mind was clear; she was quite determined, and her resolution varied not.

As soon as the servants were awake she sent a message to the Park, requesting an interview at the belvedere that morning, then made a hasty breakfast, and went out into the

garden.

By the time she heard the great clock at Mansfield chime nine, she had been waiting at the appointed place for more than an hour, and the bench offering an uninterrupted view to the house, she

was able to watch him approaching for some moments, before he was aware of her presence. His step, she saw, was measured, and his comportment upright. When she rose to her feet and walked to meet

him, she perceived, with a pang, that his step quickened.

‘Good morning, Miss Crawford.’

‘Mr Norris.’

‘I must thank you, once more,’ he continued, ‘for the kind service you have afforded my family at this sad time. I have heard from Mrs Baddeley of your exertions in the last

stages of Julia’s illness, and I know that you did all in your power to nurse her back to health. We are all, as you might imagine, quite overcome. To lose a daughter and a sister in such

terrible circumstances, and so soon after the death of her cousin, it is—well, it is intolerable. My poor uncle will come home only to preside at a double funeral, though his presence will,

at least, be an indescribable comfort to my aunt. We expect him in a few days.’

There was a silence, and he perceived, for the first time, that she had not met his gaze.

‘Miss Crawford? Are you quite well?’

‘I am very tired, Mr Norris. I will, if you permit, sit down for a few minutes.’

They walked back, without speaking, to the bench, too preoccupied by their different thoughts to notice a figure in the shadows, just

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher