![Murder at Mansfield Park]()

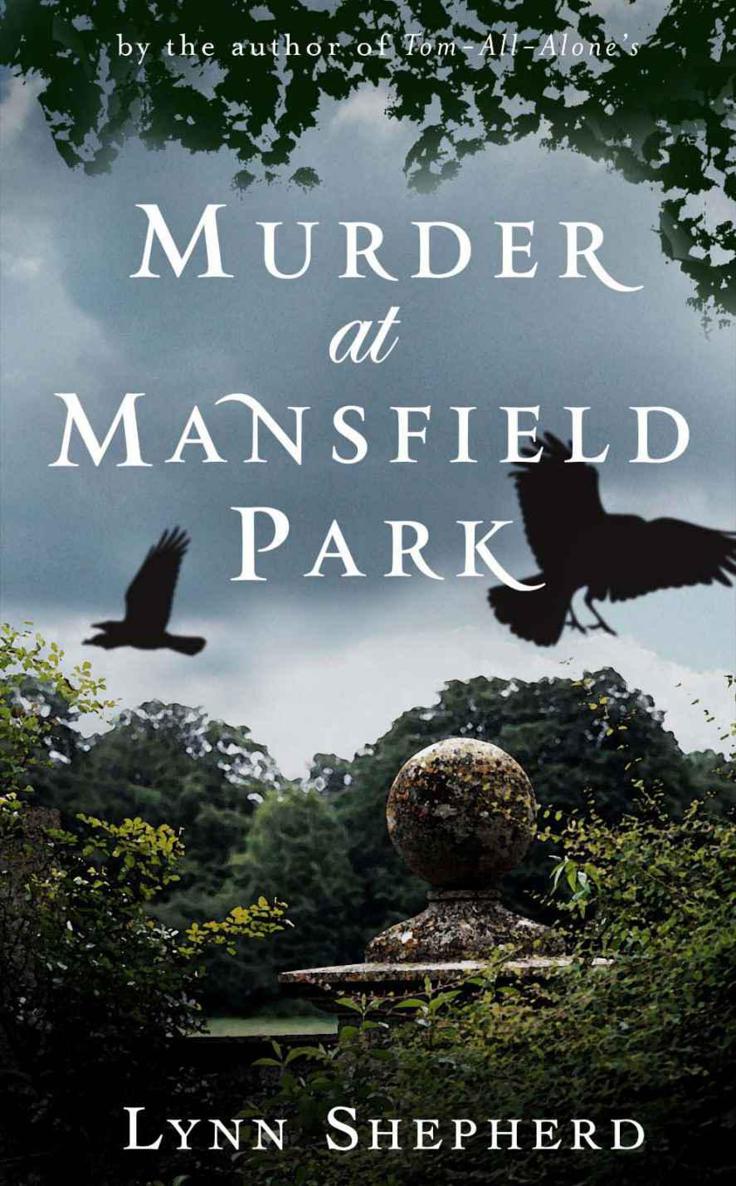

Murder at Mansfield Park

beyond the wall of the belvedere, listening intently to

every word they spoke.

Mary took her seat, and was silent a moment, endeavouring to quiet the beating of her heart.

‘I have dreaded this moment, Mr Norris, and more than once I felt my courage would fail me before I came face to face with you. Now that I am here, I beg you will hear me out. I asked to

see you because there is some thing I must tell you. It relates to your cousin.’

He frowned a little at this, but said nothing.

‘Some hours before Julia lapsed into her final lethargy, she became very distraught, and began to talk wildly. I did not perceive, at first, what had distressed her to such a dreadful

extent, but I am afraid it soon became only too clear. As you know, she was walking in the park the day Miss Price returned; I now know that she saw some thing that morning, and she was frightened

half out of her wits by the memory of it. I believe, in fact, that she saw quite clearly who it was who struck her cousin the fatal blow. She was talking incoherently about the blood—on her

face, on her hands. It must have been a barbarous thing for such a young and delicate girl to witness.’

She rose from her seat and walked forward a few paces, unable to look at him; she had hardly the strength to speak, and knew that if she did not say what she must at that very moment, she might

never be able to do so.

‘She—she—mentioned a name. I am sure you do not need me to repeat it. It is—too painful; for you to hear, or for me to utter. I only tell you this now because I am

convinced that Mr Maddox is about to arrest my brother for this crime. I, alone of everyone at Mansfield, know that he absolutely did not do this thing of which he will be accused. I therefore have

no choice but to go to Mr Maddox and tell him what I have just told you. Once I have done so, you and I will probably have no opportunity to speak; indeed,’ she said, in a broken accent,

‘we may never see each other again.’

Had Mary been able to turn towards him and encounter his eye, she would have seen in his face such agony of soul, such a confusion of contradictory emotions, as would have filled her with

compassion, however oppressed she was by quite other feelings at that moment. He rose and moved towards her, and made as if to put a hand on her shoulder, but checked himself, and turned away.

‘I am grateful,’ he said in a voice devoid of expression, ‘for the information you have been so good as to impart. I wish you good morning.’

He gave an awkward bow, and walked stiffly away.

She had enough self-control to restrain her tears until he was out of hearing, but when they came they were the bitterest tears she had ever had cause to shed. Notwithstanding Julia’s

dying words, notwithstanding the seemingly incontestable nature of what Mary had heard, she had never entirely lost the hope that he might have an innocent explanation. That he would seize her

hands, and tell her she was mistaken, that he was as blameless as her brother. But he had not. She had not seen him for some days, and in that time her knowledge of his character had undergone so

material a change, as to make her doubt her own judgment. How could she have been in love with such a man—how could she justify an affection that was not only passionate, but also, as she had

thought, rational, kindled as it had been by his modesty, gentleness, benevolence, and steadiness of mind? She must henceforth regard him as a man capable of murder, a man who could kill the woman

to whom he was betrothed in the most brutal manner, without any apparent sign of remorse. And even if it were possible for her heart to acquit him, in some measure, of the death of Fanny, on the

grounds of a sudden wild anger, or insupportable provocation, how could she ever forgive him for the part he had played in Julia’s demise—a gentle, sweet-tempered girl for whom he had

appeared to feel deep and genuine affection? And when she had confronted him with the evidence of his guilt he had merely reverted to the cold and impenetrable reserve that had characterised their

first acquaintance.

She wondered now whether Henry’s estimation of him had not been correct all along, and she had seen in Edmund some thing she had wished to see, but which bore little relation to his true

character. And much as she had tried to dismiss it, she had never fully rid herself of a slight but insistent unease she had felt ever since the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher